How To Make A Mint: The Cryptography of Anonymous Electronic Cash

Anonymous: Fried, Frank got NSA's permission to make this report available. They have offered to make copies available by contacting them at or (202) 639-7200. See: http://www.ffhsj.com/bancmail/21starch/961017.htm

Received October 31, 1996

With the Compliments of Thomas P. Vartanian

Fried, Frank, Harris, Schriver & Jacobson

1001 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20004-2505

Telephone: (202) 639-7200

Laurie Law, Susan Sabett, Jerry Solinas

National Security Agency Office of Information Security Research and Technology

Cryptology Division

18 June 1996

CONTENTS

1.1 Electronic Payment

1.2 Security of Electronic Payments

1.3 Electronic Cash

1.4 Multiple Spending

2. A CRYPTOGRAPHIC DESCRIPTION

2.1 Public-Key Cryptographic Tools

2.2 A Simplified Electronic Cash Protocol

2.3 Untraceable Electronic Payments

2.4 A Basic Electronic Cash Protocol

3. PROPOSED OFF-LINE IMPLEMENTATIONS

3.1 Including Identifying Information

3.2 Authentication and Signature Techniques

3.3 Summary of Proposed Implementations

4. OPTIONAL FEATURES OF OFF-LINE CASH

4. 1 Transferability

4.2 Divisibility

5.1 Multiple Spending Prevention

5.2 Wallet Observers

5.3 Security Failures

5.4 Restoring Traceability

With the onset of the Information Age, our nation is becoming increasingly dependent upon network communications. Computer-based technology is significantly impacting our ability to access, store, and distribute information. Among the most important uses of this technology is electronic commerce: performing financial transactions via electronic information exchanged over telecommunications lines. A key requirement for electronic commerce is the development of secure and efficient electronic payment systems. The need for security is highlighted by the rise of the Internet, which promises to be a leading medium for future electronic commerce.

Electronic payment systems come in many forms including digital checks, debit cards, credit cards, and stored value cards. The usual security features for such systems are privacy (protection from eavesdropping), authenticity (provides user identification and message integrity), and nonrepudiation (prevention of later denying having performed a transaction) .

The type of electronic payment system focused on in this paper is electronic cash. As the name implies, electronic cash is an attempt to construct an electronic payment system modelled after our paper cash system. Paper cash has such features as being: portable (easily carried), recognizable (as legal tender) hence readily acceptable, transferable (without involvement of the financial network), untraceable (no record of where money is spent), anonymous (no record of who spent the money) and has the ability to make "change." The designers of electronic cash focused on preserving the features of untraceability and anonymity. Thus, electronic cash is defined to be an electronic payment system that provides, in addition to the above security features, the properties of user anonymity and payment untraceability..

In general, electronic cash schemes achieve these security goals via digital signatures. They can be considered the digital analog to a handwritten signature. Digital signatures are based on public key cryptography. In such a cryptosystem, each user has a secret key and a public key. The secret key is used to create a digital signature and the public key is needed to verify the digital signature. To tell who has signed the information (also called the message), one must be certain one knows who owns a given public key. This is the problem of key management, and its solution requires some kind of authentication infrastructure. In addition, the system must have adequate network and physical security to safeguard the secrecy of the secret keys.

This report has surveyed the academic literature for cryptographic techniques for implementing secure electronic cash systems. Several innovative payment schemes providing user anonymity and payment untraceability have been found. Although no particular payment system has been thoroughly analyzed, the cryptography itself appears to be sound and to deliver the promised anonymity.

These schemes are far less satisfactory, however, from a law enforcement point of view. In particular, the dangers of money laundering and counterfeiting are potentially far more serious than with paper cash. These problems exist in any electronic payment system, but they are made much worse by the presence of anonymity. Indeed, the widespread use of electronic cash would increase the vulnerability of the national financial system to Information Warfare attacks. We discuss measures to manage these risks; these steps, however, would have the effect of limiting the users' anonymity.

This report is organized in the following manner. Chapter 1 defines the basic concepts surrounding electronic payment systems and electronic cash. Chapter 2 provides the reader with a high level cryptographic description of electronic cash protocols in terms of basic authentication mechanisms. Chapter 3 technically describes specific implementations that have been proposed in the academic literature. In Chapter 4, the optional features of transferability and divisibility for off-line electronic cash are presented. Finally, in Chapter 5 the security issues associated with electronic cash are discussed.

The authors of this paper wish to acknowledge the following people for their contribution to this research effort through numerous discussions and review of this paper: Kevin Igoe, John Petro, Steve Neal, and Mel Currie.

We begin by carefully defining "electronic cash." This term is often applied to any electronic payment scheme that superficially resembles cash to the user. In fact, however, electronic cash is a specific kind of electronic payment scheme, defined by certain cryptographic properties. We now focus on these properties.

1.1 Electronic Payment

The term electronic commerce refers to any financial transaction involving the electronic transmission of information. The packets of information being transmitted are commonly called electronic tokens. One should not confuse the token, which is a sequence of bits, with the physical media used to store and transmit the information.

We will refer to the storage medium as a card since it commonly takes the form of a wallet-sized card made of plastic or cardboard. (Two obvious examples are credit cards and ATM cards.) However, the "card" could also be, e.g., a computer memory.

A particular kind of electronic commerce is that of electronic payment. An electronic payment protocol is a series of transactions, at the end of which a payment has been made, using a token issued by a third party. The most common example is that of credit cards when an electronic approval process is used. Note that our definition implies that neither payer nor payee issues the token.l

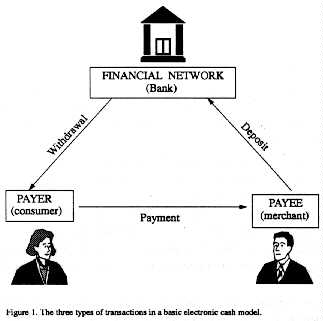

The electronic payment scenario assumes three kinds of players:2

- a payer or consumer, whom we will name Alice.

- a payee, such as a merchant. We will name the payee Bob.

- a financial network with whom both Alice and Bob have accounts. We will informally refer to the financial network as the Bank.

__________

1 In this sense, electronic payment differs from such systems as prepaid phone cards and subway fare cards, where the token is issued by the payee.

2 In 4.1, we will generalize this scenario when we discuss transfers.

1.2 Security of Electronic Payments

With the rise of telecommunications and the Internet, it is increasingly the case that electronic commerce takes place using a transmission medium not under the control of the financial system. It is therefore necessary to take steps to insure the security of the messages sent along such a medium.

The necessary security properties are:

- Privacy, or protection against eavesdropping. This is obviously of importance for transactions involving, e.g., credit card numbers sent on the Internet.

- User identification, or protection against impersonation. Clearly, any scheme for electronic commerce must require that a user knows with whom she is dealing (if only as an alias or credit card number).

- Message integrity, or protection against tampering or substitution. One must know that the recipient's copy of the message is the same as what was sent.

- Nonrepudiation, or protection against later denial of a transaction. This is clearly necessary for electronic commerce, for such things as digital receipts and payments.

The last three properties are collectively referred to as authenticity.

These security features can be achieved in several ways. The technique that is gaining widespread use is to employ an authentication infrastructure. In such a setup, privacy is attained by enciphering each message, using a private key known only to the sender and recipient. The authenticity features are attained via key management, e.g., the system of generating, distributing and storing the users' keys.

Key management is carried out using a certification authority, or a trusted agent who is responsible for confirming a user's identity. This is done for each user (including banks) who is issued a digital identity certificate. The certificate can be used whenever the user wishes to identify herself to another user. In addition, the certificates make it possible to set up a private key between users in a secure and authenticated way. This private key is then used to encrypt subsequent messages. This technique can be implemented to provide any or all of the above security features.

Although the authentication infrastructure may be separate from the electronic-commerce setup, its security is an essential component of the security of the electronic-commerce system. Without a trusted certification authority and a secure infrastructure, the above four security features cannot be achieved, and electronic commerce becomes impossible over an untrusted transmission medium.

We will assume throughout the remainder of this paper that some authentication infrastructure is in place, providing the four security features.

1.3 Electronic Cash

We have defined privacy as protection against eavesdropping on one's communications. Some privacy advocates such as David Chaum (see [2],[3]), however, define the term far more expansively. To them, genuine "privacy" implies that one's history of purchases not be available for inspection by banks and credit card companies (and by extension the government). To achieve this, one needs not just privacy but anonymity. In particular, one needs

- payer anonymity during payment,

- payment untraceability so that the Bank cannot tell whose money is used in a particular payment.

These features are not available with credit cards. Indeed, the only conventional payment system offering it is cash. Thus Chaum and others have introduced electronic cash (or digital cash), an electronic payment system which offers both features. The sequence of events in an electronic cash payment is as follows:

- withdrawal, in which Alice transfers some of her wealth from her Bank account to her card.

- payment, in which Alice transfers money from her card to Bob's.

- deposit, in which Bob transfers the money he has received to his Bank account.

(See Figure 1.)

Figure 1. The three types of transactions in a basic electronic cash model.

These procedures can be implemented in either of two ways:

- On-line payment means that Bob calls the Bank and verifies the validity of Alice's token3 before accepting her payment and delivering his merchandise. (This resembles many of today's credit card transactions.)

- Off-line payment means that Bob submits Alice's electronic coin for verification and deposit sometime after the payment transaction is completed. (This method resembles how we make small purchases today by personal check.)

Note that with an on-line system, the payment and deposit are not separate steps. We will refer to on-line cash and off-line cash schemes, omitting the word "electronic" since there is no danger of confusion with paper cash.

__________

3 In the context of electronic cash, the token is usually called an electronic coin.

1.4 Counterfeiting

As in any payment system, there is the potential here for criminal abuse, with the intention either of cheating the financial system or using the payment mechanism to facilitate some other crime. We will discuss some of these problems in 5. However, the issue of counterfeiting must be considered here, since the payment protocols contain built-in protections against it.

There are two abuses of an electronic cash system analogous to counterfeiting of physical cash:

- Token forgery, or creating a valid-looking coin without making a corresponding Bank withdrawal.

- Multiple spending, or using the same token over again. Since an electronic coin consists of digital information, it is as valid-looking after it has been spent as it was before. (Multiple spending is also commonly called re-spending, double spending, and repeat spending.)

One can deal with counterfeiting by trying to prevent it from happening, or by trying to detect it after the fact in a way that identifies the culprit. Prevention clearly is preferable, all other things being equal.

Although it is tempting to imagine electronic cash systems in which the transmission and storage media are secure, there will certainly be applications where this is not the case. (An obvious example is the Internet, whose users are notoriously vulnerable to viruses and eavesdropping.) Thus we need techniques of dealing with counterfeiting other than physical security.

- To protect against token forgery, one relies on the usual authenticity functions of user identification and message integrity. (Note that the "user" being identified from the coin is the issuing Bank, not the anonymous spender.)

- To protect against multiple spending, the Bank maintains a database of spent electronic coins. Coins already in the database are to be rejected for deposit. If the payments are on-line, this will prevent multiple spending. If off-line, the best we can do is to detect when multiple spending has occurred. To protect the payee, it is then necessary to identify the payer. Thus it is necessary to disable the anonymity mechanism in the case of multiple spending.

The features of authenticity, anonymity, and multiple-spender exposure are achieved most conveniently using public-key cryptography. We will discuss how this is done in the next two chapters.

In this chapter, we give a high-level description of electronic cash protocols in terms of basic authentication mechanisms. We begin by describing these mechanisms, which are based on public-key cryptography. We then build up the protocol gradually for ease of exposition. We start with a simplified scheme which provides no anonymity. We then incorporate the payment untraceability feature, and finally the payment anonymity property. The result will be a complete electronic cash protocol.

2.1 Public-Key Cryptographic Tools

We begin by discussing the basic public-key cryptographic techniques upon which the electronic cash implementations are based.

One-Way Functions. A one-way function is a correspondence between two sets which can be computed efficiently in one direction but not the other. In other words, the function phi is one-way if, given s in the domain of phi, it is easy to compute t = phi(s), but given only t, it is hard to find s. (The elements are typically numbers, but could also be, e.g., points on an elliptic curve; see [10].)

Key Pairs. If phi is a one-way function, then a key pair is a pair s, t related in some way via phi. We call s the secret key and t the public key. As the names imply, each user keeps his secret key to himself and makes his public key available to all. The secret key remains secret even when the public key is known, because the one-way property of phi insures that t cannot be computed from s.

All public-key protocols use key pairs. For this reason, public-key cryptography is often called asymmetric cryptography. Conventional cryptography is often called symmetric cryptography, since one can both encrypt and decrypt with the private key but do neither without it.

Signature and Identification. In a public key system, a user identifies herself by proving that she knows her secret key without revealing it. This is done by performing some operation using the secret key which anyone can check or undo using the public key. This is called identification. If one uses a message as well as one's secret key, one is performing a digital signature on the message. The digital signature plays the same role as a handwritten signature: identifying the author of the message in a way which cannot be repudiated, and confirming the integrity of the message.

Secure Hashing. A hash function is a map from all possible strings of bits of any length to a bit string of fixed length. Such functions are often required to be collision-free: that is, it must be computationally difficult to find two inputs that hash to the same value. If a hash function is both one-way and collision-free, it is said to be a secure hash.

The most common use of secure hash functions is in digital signatures. Messages might come in any size, but a given public-key algorithm requires working in a set of fixed size. Thus one hashes the message and signs the secure hash rather than the message itself. The hash is required to be one-way to prevent signature forgery, i.e., constructing a valid-looking signature of a message without using the secret key.4 The hash must be collision-free to prevent repudiation, i.e., denying having signed one message by producing another message with the same hash.

__________

4 Note that token forgery is not the same thing as signature forgery. Forging the Bank's digital signature without knowing its secret key is one way of committing token forgery, but not the only way. A bank employee or hacker, for instance, could "borrow" the Bank's secret key and validly sign a token. This key compromise scenario is discussed in 5.3.

2.2 A Simplified Electronic Cash Protocol

We now present a simplified electronic cash system, without the anonymity features.

PROTOCOL 1:On-line electronic payment.

Withdrawal:

Alice sends a withdrawal request to the Bank.

Bank prepares an electronic coin and digitally signs it.

Bank sends coin to Alice and debits her account.

Payment/Deposit:

Alice gives Bob the coin.

Bob contacts Bank5 and sends coin.

Bank verifies the Bank's digital signature.

Bank verifies that coin has not already been spent.

Bank consults its withdrawal records to confirm Alice's withdrawal. (optional)

Bank enters coin in spent-coin database.

Bank credits Bob's account and informs Bob.

Bob gives Alice the merchandise.

__________

5 One should keep in mind that the term "Bank" refers to the financial system that issues and clears the coins. For example, the Bank might be a credit card company, or the overall banking system. In the latter case, Alice and Bob might have separate banks. If that is so, then the "deposit" procedure is a little more complicated: Bob's bank contacts Alice's bank, "cashes in" the coin, and puts the money in Bob's account.

PROTOCOL 2:Off-line electronic payment.

Withdrawal:

Alice sends a withdrawal request to the Bank.

Bank prepares an electronic coin and digitally signs it.

Bank sends coin to Alice and debits her account.

Payment:

Alice gives Bob the coin.

Bob verifies the Bank's digital signature. (optional)

Bob gives Alice the merchandise.

Deposit:

Bob sends coin to the Bank.

Bank verifies the Bank's digital signature.

Bank verifies that coin has not already been spent.

Bank consults its withdrawal records to confirm Alice's withdrawal. (optional)

Bank enters coin in spent-coin database.

Bank credits Bob's account.

The above protocols use digital signatures to achieve authenticity. The authenticity features could have been achieved in other ways, but we need to use digital signatures to allow for the anonymity mechanisms we are about to add.

2.3 Untraceable Electronic Payments

In this section, we modify the above protocols to include payment untraceability. For this, it is necessary that the Bank not be able to link a specific withdrawal with a specific deposit.6 This is accomplished using a special kind of digital signature called a blind signature.

We will give examples of blind signatures in 3.2, but for now we give only a high-level description. In the withdrawal step, the user changes the message to be signed using a random quantity. This step is called "blinding" the coin, and the random quantity is called the blinding factor. The Bank signs this random-looking text, and the user removes the blinding factor. The user now has a legitimate electronic coin signed by the Bank. The Bank will see this coin when it is submitted for deposit, but will not know who withdrew it since the random blinding factors are unknown to the Bank. (Obviously, it will no longer be possible to do the checking of the withdrawal records that was an optional step in the first two protocols.)

Note that the Bank does not know what it is signing in the withdrawal step. This introduces the possibility that the Bank might be signing something other than what it is intending to sign. To prevent this, we specify that a Bank's digital signature by a given secret key is valid only as authorizing a withdrawal of a fixed amount. For example, the Bank could have one key for a $10 withdrawal, another for a $50 withdrawal, and so on.7

_________

6 In order to achieve either anonymity feature, it is of course necessary that the pool of electronic coins be a large one.

7 0ne could also broaden the concept of "blind signature" to include interactive protocols where both parties contribute random elements to the message to be signed. An example of this is the "randomized blind signature" occurring in the Ferguson scheme discussed in 3.3.

PROTOCOL 3:Untraceable On-line electronic payment.

Withdrawal:

Alice creates an electronic coin and blinds it.

Alice sends the blinded coin to the Bank with a withdrawal request.

Bank digitally signs the blinded coin.

Bank sends the signed blinded coin to Alice and debits her account.

Alice unblinds the signed coin.

Payment/Deposit:

Alice gives Bob the coin.

Bob contacts Bank and sends coin.

Bank verifies the Bank's digital signature.

Bank verifies that coin has not already been spent.

Bank enters coin in spent-coin database.

Bank credits Bob's account and informs Bob.

Bob gives Alice the merchandise.

PROTOCOL 4:Untraceable Off-line electronic payment.

Withdrawal:

Alice creates an electronic coin and blinds it.

Alice sends the blinded coin to the Bank with a withdrawal request.

Bank digitally signs the blinded coin.

Bank sends the signed blinded coin to Alice and debits her account.

Alice unblinds the signed coin.

Payment:

Alice gives Bob the coin.

Bob verifies the Bank's digital signature. (optional)

Bob gives Alice the merchandise.

Deposit:

Bob sends coin to the Bank.

Bank verifies the Bank's digital signature.

Bank verifies that coin has not already been spent.

Bank enters coin in spent-coin database.

Bank credits Bob's account.

2.4 A Basic Electronic Cash Protocol

We now take the final step and modify our protocols to achieve payment anonymity. The ideal situation (from the point of view of privacy advocates) is that neither payer nor payee should know the identity of the other. This makes remote transactions using electronic cash totally anonymous: no one knows where Alice spends her money and who pays her.

It turns out that this is too much to ask: there is no way in such a scenario for the consumer to obtain a signed receipt. Thus we are forced to settle for payer anonymity.

If the payment is to be on-line, we can use Protocol 3 (implemented, of course, to allow for payer anonymity). In the off-line case, however, a new problem arises. If a merchant tries to deposit a previously spent coin, he will be turned down by the Bank, but neither will know who the multiple spender was since she was anonymous. Thus it is necessary for the Bank to be able to identify a multiple spender. This feature, however, should preserve anonymity for law-abiding users.

The solution is for the payment step to require the payer to have, in addition to her electronic coin, some sort of identifying information which she is to share with the payee. This information is split in such a way that any one piece reveals nothing about Alice's identity, but any two pieces are sufficient to fully identify her.

This information is created during the withdrawal step. The withdrawal protocol includes a step in which the Bank verifies that the information is there and corresponds to Alice and to the particular coin being created. (To preserve payer anonymity, the Bank will not actually see the information, only verify that it is there.) Alice carries the information along with the coin until she spends it.

At the payment step, Alice must reveal one piece of this information to Bob. (Thus only Alice can spend the coin, since only she knows the information.) This revealing is done using a challenge-response protocol. In such a protocol, Bob sends Alice a random "challenge" quantity and, in response, Alice returns a piece of identifying information. (The challenge quantity determines which piece she sends.) At the deposit step, the revealed piece is sent to the Bank along with the coin. If all goes as it should, the identifying information will never point to Alice. However, should she spend the coin twice, the Bank will eventually obtain two copies of the same coin, each with a piece of identifying information. Because of the randomness in the challenge-response protocol, these two pieces will be different. Thus the Bank will be able to identify her as the multiple spender. Since only she can dispense identifying information, we know that her coin was not copied and re-spent by someone else.

PROTOCOL 5:Off-line cash.

Withdrawal:

Alice creates an electronic coin, including identifying information.

Alice blinds the coin.

Alice sends the blinded coin to the Bank with a withdrawal request.

Bank verifies that the identifying information is present.

Bank digitally signs the blinded coin.

Bank sends the signed blinded coin to Alice and debits her account.

Alice unblinds the signed coin.

Payment:

Alice gives Bob the coin.

Bob verifies the Bank's digital signature.

Bob sends Alice a challenge.

Alice sends Bob a response (revealing one piece of identifying info).

Bob verifies the response.

Bob gives Alice the merchandise.

Deposit:

Bob sends coin, challenge, and response to the Bank.

Bank verifies the Bank's digital signature.

Bank verifies that coin has not already been spent.

Bank enters coin, challenge, and response in spent-coin database.

Bank credits Bob's account.

Note that, in this protocol, Bob must verify the Bank's signature before giving Alice the merchandise. In this way, Bob can be sure that either he will be paid or he will learn Alice's identity as a multiple spender.

Having described electronic cash in a high-level way, we now wish to describe the specific implementations that have been proposed in the literature. Such implementations are for the off-line case; the on-line protocols are just simplifications of them. The first step is to discuss the various implementations of the public-key cryptographic tools we have described earlier.

3.1 Including Identifying Information

We must first be more specific about how to include (and access when necessary) the identifying information meant to catch multiple spenders. There are two ways of doing it: the cut-and-choose method and zero-knowledge proofs.

Cut and Choose. When Alice wishes to make a withdrawal, she first constructs and blinds a message consisting of K pairs of numbers, where K is large enough that an event with probability 2-K will never happen in practice. These numbers have the property that one can identify Alice given both pieces of a pair, but unmatched pieces are useless. She then obtains signature of this blinded message from the Bank. (This is done in such a way that the Bank can check that the K pairs of numbers are present and have the required properties, despite the blinding.)

When Alice spends her coins with Bob, his challenge to her is a string of K random bits. For each bit, Alice sends the appropriate piece of the corresponding pair. For example, if the bit string starts 0110. . ., then Alice sends the first piece of the first pair, the second piece of the second pair, the second piece of the third pair, the first piece of the fourth pair, etc. When Bob deposits the coin at the Bank, he sends on these K pieces.

If Alice re-spends her coin, she is challenged a second time. Since each challenge is a random bit string, the new challenge is bound to disagree with the old one in at least one bit. Thus Alice will have to reveal the other piece of the corresponding pair. When the Bank receives the coin a second time, it takes the two pieces and combines them to reveal Alice's identity.

Although conceptually simple, this scheme is not very efficient, since each coin must be accompanied by 2K large numbers.

Zero-Knowledge Proofs. The term zero-knowledge proof refers to any protocol in public-key cryptography that proves knowledge of some quantity without revealing it (or making it any easier to find it). In this case, Alice creates a key pair such that the secret key points to her identity. (This is done in such a way the Bank can check via the public key that the secret key in fact reveals her identity, despite the blinding.) In the payment protocol, she gives Bob the public key as part of the electronic coin. She then proves to Bob via a zero-knowledge proof that she possesses the corresponding secret key. If she responds to two distinct challenges, the identifying information can be put together to reveal the secret key and so her identity.

3.2 Authentication and Signature Techniques

Our next step is to describe the digital signatures that have been used in the implementations of the above protocols, and the techniques that have been used to include identifying information.

There are two kinds of digital signatures, and both kinds appear in electronic cash protocols. Suppose the signer has a key pair and a message M to be signed.

- Digital Signature with Message Recovery. For this kind of signature, we have a signing function SSK using the secret key SK, and a verifying function VPK using the public key PK. These functions are inverses, so that

(*) VPK (SSK (M)) = M

- The function VPK is easy to implement, while SSK is easy if one knows SK and difficult otherwise. Thus SSK is said to have a trapdoor, or secret quantity that makes it possible to perform a cryptographic computation which is otherwise infeasible. The function VPK is called a trapdoor one-way function, since it is a one-way function to anyone who does not know the trapdoor.

- In this kind of scheme, the verifier receives the signed message SSK (M) but not the original message text. The verifier then applies the verification function VPK. This step both verifies the identity of the signer and, by (*), recovers the message text.

- Digital Signature with Appendix. In this kind of signature, the signer performs an operation on the message using his own secret key. The result is taken to be the signature of the message; it is sent along as an appendix to the message text. The verifier checks an equation involving the message, the appendix, and the signer's public key. If the equation checks, the verifier knows that the signer's secret key was used in generating the signature.

We now give specific algorithms.

RSA Signatures. The most well-known signature with message recovery is the RSA signature. Let N be a hard-to-factor integer. The secret signature key s and the public verification key v are exponents with the property that

Msv = M (mod N)

for all messages M. Given v, it is easy to find s if one knows the factors of N but difficult otherwise. Thus the "vth power (mod N)" map is a trapdoor one-way function. The signature of M is

C := Ms (mod N);

to recover the message (and verify the signature), one computes

M := Cv (mod N).

Blind RSA Signatures. The above scheme is easily blinded. Suppose that Alice wants the Bank to produce a blind signature of the message M. She generates a random number r and sends

rv . M (mod N)

to the Bank to sign. The Bank does so, returning

r . Ms (mod N)

Alice then divides this result by r. The result is Ms (mod N), the Bank's signature of M, even though the Bank has never seen M.

The Schnorr Algorithms. The Schnorr family of algorithms includes an identification procedure and a signature with appendix. These algorithms are based on a zero-knowledge proof of possession of a secret key. Let p and q be large prime numbers with q dividing p - 1. Let g be a generator; that is, an integer between 1 and p such that

gq = 1 (mod p).

If s is an integer (mod q), then the modular exponentiation operation on s is

phi : s -> gs (mod p).

The inverse operation is called the discrete logarithm function and is denoted

loggt