Not All Is Lost In Turkey « The Jerusalem Review

Turkey’s political forecast may be increasingly murky, but its energy security has never been more stable.

By: Nicholas Borroz

In the last few weeks, Turkey took an important step towards improving its energy security: on January 2nd, Turkish Energy Minister Taner Yildiz announced that crude oil had started flowing to the Turkish port of Ceyhan from Iraqi Kurdistan. Most media coverage of Turkey is currently focusing on the destabilizing effects of an ongoing corruption scandal, which commentators warn threatens both democracy and foreign capital inflows. These setbacks, while significant, should not overshadow the recent positive developments for Turkey’s energy security.

ENERGY INSECURITY

The primary reason for Turkey’s deepening ties with Iraqi Kurdistan, as exemplified by Yildiz’s announcement, is that Turkey is driven to improve its energy security and gain access to new hydrocarbon supplies. Despite being well-known for its identity as an energy hub, Turkey is ironically bereft of its own natural oil and gas resources. Turkey is almost entirely dependent on oil and gas imports to meet its domestic consumption needs. In 2011, for instance, Turkey met more than 90 percent of its liquid fuels consumption with imports. Such dependence on foreign suppliers is an uncomfortable position for a developing economy such as Turkey. This is particularly true because its energy consumption is expected to increase dramatically over the next decade.

LIMITED IMPORT PORTFOLIO

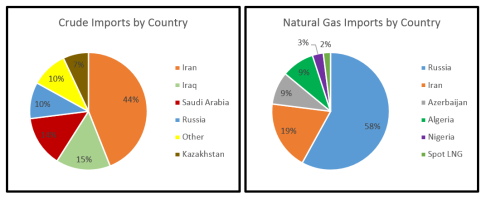

Beyond being simply dependent on energy imports, Turkey is overly dependent on a limited number of less-than-reputable suppliers, namely Russia and Iran. Adding Iraqi Kurdistan as an oil supplier, and also eventually as a potential natural gas supplier, helps Turkey to diversify its import portfolio. As reported by the US Energy Information Agency, Iran and Russia are respectively Turkey’s largest suppliers of oil and gas:

The dependence illustrated in the previous graphs is particularly troubling since neither Russia nor Iran are known for being dependable energy exporters. For instance, in 2009, Russia stopped the flow of gas to Ukraine, showing that it is comfortable with using its control of energy supplies to exert political pressure, a fact already well known by many eastern European countries. Furthermore, Russia’s extractive industry is aging and lacking in innovation, which puts into question its future ability to competitively extract oil and gas. Iran, on the other hand, has been crippled by international sanctions. Even if these sanctions are lifted, which seems more possible now than ever before, it will take significant time for Iran’s hydrocarbon industry to recover its production potential. Additionally, Iran’s oil and gas infrastructure is aging and inefficient, which has led it to regularly fall short in its gas delivery promises to Turkey in the past.

Iraq in general, and Iraqi Kurdistan in particular, is an obvious choice for Turkey when it looks at options to diversify its hydrocarbon supplies. Coming from right across the border amidst vast oil and gas reserves, the new Iraqi Kurdistan oil flow augurs an improvement for Turkey’s energy import portfolio in terms of diversification.

SECURITY CONCERNS

Another benefit to the Iraqi Kurdistan oil is that, unlike the oil from Iraq in general, this supply promises to be much more stable. The major oil artery from Iraq to Turkey is the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline (shown in red on the map below), which is regularly bombed by insurgents in Iraq. As a result, oil flows are often stopped for repairs. The majority of those attacks, as reported in open-source media, occur in the governorates of Ninawa and Salah ad-Din (underlined in blue on the map below). Iraqi Kurdistan (shaded green on the map below) is removed from most of the violence.

Iraqi Kurdistan is relatively stable when compared to the rest of Iraq. Since the US invasion in 2003, Iraq’s Kurds have carved out a political entity that is largely independent from the turmoil and strife that regularly wracks Iraq’s other regions.

Within this relative safe haven, new pipelines are being developed, the details of which are as of yet unclear. Media reports, however, indicate that multiple pipelines were under construction as of November. The Iraqi Kurdistan oil would also still have the potential to flow through Iraq’s Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline if an accord is reached between Baghdad and Erbil. This variety of potential transportation routes provides the Iraqi Kurdistan oil with an added advantage: it is not dependent on a sole pipeline to reach Iraq. Whereas the Iraqi oil flow to Turkey is often shut down due to devastating bomb attacks on the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline, the Iraqi Kurdistan oil has greater strategic flexibility because of its multiple potential transit routes.

CAUTIOUS OPTIMISM?

Despite the media’s focus on the destabilizing effects of the ongoing corruption scandal in Turkey, the news of the new oil flow from Iraqi Kurdistan to Turkey indicates that the country is also experiencing noteworthy improvement to its energy security. This seems likely to have a positive impact on the country’s overall stability. A slew of other factors must be considered to fully understand Turkey’s status and how it will change in the near future. For the moment though, the new pipeline indicates that not all is lost in Turkey, no matter what the alarmists are reporting.

Nicholas Borroz is a staff writer at The Jerusalem Review of Near East Affairs.

Photo credit: Flickr Commons

Like this:

LikeLoading...