chemical warfare | Technology and Security

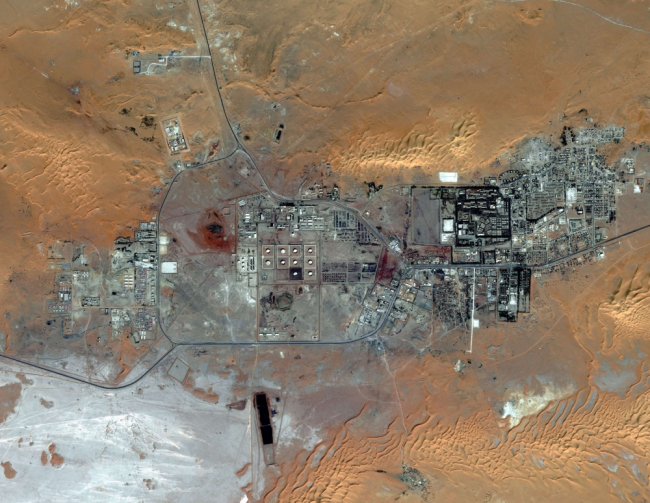

The Amenas Gas Field in Algeria is seen in this October 8, 2012 handout image courtesy of DigitalGlobe

By Stephen Bryen

News reports from Algeria tell us that the hostage siege at the Ain Amenas Gas Plant in the Sahara is now over, but the final list of casualties remains uncertain. So far we know that the operation resulted in the escape or release of some 685 Algerian workers and 107 foreigners. Current information says that 23 hostages are confirmed dead; another 25 bodies, presumed to be hostages, have so far been found in buildings. There are probably more deaths as a number of vehicles were struck by Algerian Air Force helicopters and destroyed, and these vehicles are said to have been carrying both hostages and terrorists. The Algerians report that “all” 32 terrorists were killed.

There has been serious criticism of the Algerian Army and Special Forces raid and claims they did a poor job resulting in an excess of civilian deaths. From information so far that is available, about 6% (six percent) of the hostages died during the operation. Possibly the number will rise, but it is unlikely to exceed 10%.

Is this a bad result or a good result?

In October, 2002, Chechen terrorists took over the Dubrovka theater in Moscow. There were some 850 hostages trapped in the theater and around 40 to 50 Chechen terrorists. The Russians tried to negotiate, over the course of a number of days, with the Chechens but no solution was found. Meanwhile the Chechens had executed a few of the hostages for various reasons.

On October 26 Russian Special Forces flooded the theater with a chemical agent, pumping it in through the ventilation system. Following this the Russian forces poured into the building and killed all the terrorists. Of the hostages 117 died as a result of the gas.

The incapacitating agent has never been officially identified but it is something called by the Russians Kolokol-1. Kolokol-1 is likely a morphine derivative that is aerosolized and based on fentanyl. The actual compound is 3-methylfentanyl.

In evaluating the Russian operation it can be seen that the number of civilian casualties was particularly high –roughly 15%. Many of the hostages, when freed, required urgent medical treatment. There is an antidote for Kolokol-1, but it must be administered quickly to work.

Poison gases intended to maim or kill are regarded as chemical agents and are banned under the Geneva Convention and the Chemical Weapons Convention. Kolokol-1 straddles the fence of legality, because while it is not intended to kill, it is a potent substance (1,000 times stronger than morphine) and, as the Moscow theater case shows, can be quite lethal.

Physically, the Moscow theater episode occurred in a closed building that was barricaded and filled with 40 or 50 heavily armed killers equipped with explosives, automatic weapons, grenades and RPG’s. If the Russian Special Forces had operated in the same way as the Algerian forces, and attacked with conventional arms, it is likely that the death count may have been higher than it was because of the lack of space to pick out targets. Perhaps other weapons, such as stun grenades, may have helped; but it is unlikely to have been effective given the mass of people and the determination of the Chechens.

If comparisons are used, the Algerians did “better”(6% to 10% versus 15%) than the Russians. Of course, the physical space of operations was markedly different.

Just last month the U.S. Consul in Turkey reported in a “secret” cable (which was leaked) that the Syrians used chemical weapons in Homs on December 23rd. The chemical weapon identified is called by the Syrians Agent 15 and, in fact, it is a CX-level incapacitating agent that causes some temporary sickness and disorientation. The agent is probably 3-Quinuclidinyl benzilate, which is a compound related to atropine (which itself is an antidote for nerve gas). This compound is “controlled” under the Chemical Weapons Convention although Syria is not a signatory to the convention. States who signed the convention should have destroyed chemical weapons and weapons manufacturing by last year, but Level 2 materials are not actually required to be destroyed. (Level 2 or Schedule 2 chemicals supposedly have legitimate small-scale applications. Manufacture must be declared and there are restrictions on export to countries which are not CWC signatories.)

The issue of incapacitating agents is not resolved under the Convention and most countries have them, including the U.S. Probably for this reason the State Department was encouraged to not denounce the Syrian regime for using chemical weapons in Homs.

Would a more effective incapacitating agent have been better than the military assault carried out by the Algerians? It is far from clear, but it may be that more research into less lethal, but more effective, incapacitating agents that can work in open areas rapidly and effectively would make sense (especially if the lethal characteristics of such materials can be mitigated). Of course this means that chemically based incapacitating agents can be an important element in future counter terror operations. While there is no public discussion as yet, research in this area seems warranted and urgent.

No one should fault either the Russians or the Algerians for standing up to a terrorist attack and doing their best under extremely difficult circumstances. Perhaps in future they will have even better tools and such incidents will result in fewer casualties.