Here's why women have turned the "not all men" objection into a meme - Vox

Over the past few weeks, the meme "not all men" — meant to satirize men who derail conversations about sexism by noting that "not all men" do X, Y, or Z sexist thing — has exploded in usage:

But it would appear that not all men (and not all people generally) are fully caught up on the meme, where it comes from, and the point it's getting across. Here's a brief history of the term, and why it's taken on such resonance lately.

1) What is a man?

Might as well start here. A man is an adult male of the species homo sapiens. To clarify, "adult" here does not mean someone who's able to pay their own rent, or treat others with respect. Adult simply means that this male has gone through puberty and is no longer a boy.

Some additional notes about men:

- A man is someone who pays his female employees less.

- A man is someone who interrupts a woman when she's in the middle of saying something.

- A man expects his wife to do all the cooking and cleaning.

What's that you say? Not ALL men pay their employees less? Not ALL men interrupt women?

Thanks for pointing that out. You're who this meme is about.

2) What is "Not all men"?

Let's say a post is written on the internet about how men do not listen to women when they speak and interrupt them more often than men, an observation borne out by empirical research. At a blog or site of sufficient size, it's practically inevitable that a commenter will reply, "Not all men interrupt."

This phrase "Not all men" is a common rebuttal used (most often) by men in conversations about gender in order to exempt themselves from criticism of common male behaviors. Recently, the phrase has been reappropriated by feminists and turned into a meme meant to parody its pervasiveness and bad faith.

3) How did "Not all men" start?

The exact origins of "not all men" are muddy at best. As Jess Zimmerman noted in Time, "'not all men' erupted in several places on the Internet simultaneously and independently, like the invention of calculus."

"Not all men" may be a shortened version of "Not all men are like that" or NAMALT, which appeared on the chat forum eNotAlone as early as 2004. The Awl's John Hermann traced mentions of "Not all men" back to 1863.

The first use of "Not all men" in a popular medium is what Shafiqah Hudson calls her "tweet heard round the world," which she published in February of 2013:

The tweet went viral almost immediately. Hudson tells me that more than a year later, it still resurfaces in her mentions at least once a month.

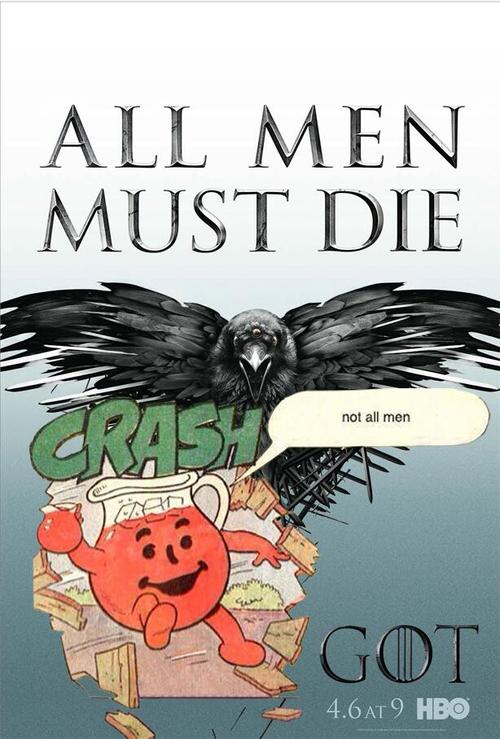

Whether Hudson's initial 2013 tweet is related to what came next is unknown. The next version of it that she saw was this tweet, which photoshopped the phrase into a Kool-Aid Man comic, more than a year later:

A few weeks later there was a "Not all men" tumblr, and re imagined movie scenes.

notallmen.tumblr.com

Matt Lubchansky, author of the comic seriesPlease Listen to Me, devoted astripto the Not-All-Man.Hudson says that neither the user who created the Koolaid meme nor Lubchansky follow her on twitter, so whether her initial tweet influenced them or not is unknown. After Lubchansky's comic, the joke hit a nerve and blew up. Comedian Paul F. Tompkins added a joke about "not all men." John Scalzi, a science fiction writer went on aTwitter rantabout "not all men." Soon it got picked up by Erin Gloria Ryan atJezebel, and Zimmermann atTime.

4) What's so bad about "Not All Men"?

When a man (though, of course, not all men) butts into a conversation about a feminist issue to remind the speaker that "not all men" do something, they derail what could be a productive conversation. Instead of contributing to the dialogue, they become the center of it, excluding themselves from any responsibility or blame.

"Men who just insist on you having that little qualifier because it undermines your argument and recenters their feelings as the central part of the dialogue," Hudson says.

On a very basic level, "not all men" is an interruption, and interrupting is rude. More to the point, it's rude in a very gendered way. Studies have shown that not all interrupting is equal. The meta analysis by the University of California at Santa Cruz was conducted on 43 studies about interrupting. It was found that men interrupted more than women only marginally, but they were much more likely to interrupt with an intention to usurp the conversation as a sign of dominance, or intrusive interrupting. Additionally, a study of group conversation dynamics showed that the gender combination of a group affects the method of interrupting. In an all-male group, the men interrupted with positive, supportive comments, but as women were added to the group, the supportive comments dwindled.

"Not all men." Fine. But pointing out individual exceptions doesn't help us understand or combat behaviors that really are mainly committed by men, from small things like interruptions up to domestic violence and rape. Not all men beat their partners, but people who beat their partners are mostly men. Pointing out that you're not one of them doesn't help us figure out how to understand and deal with that problem.

5) Wait. So how is "Not all men" different from "mansplaining"?

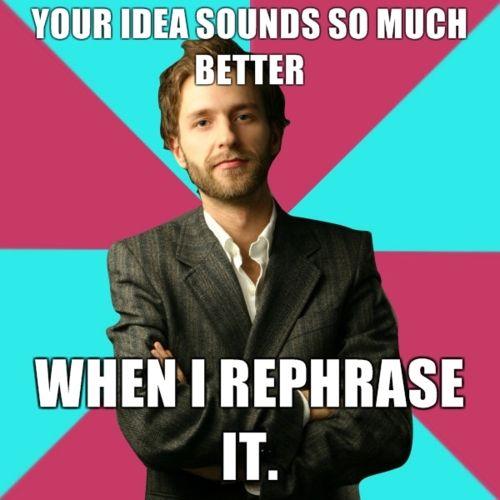

Mansplaining is a term used to describe an explanation that is given in a condescending, patronizing tone. Though a woman could be guilty of mansplaining, the idea originated from men talking down to women in order to explain things, often things the women in question understand better than the mansplainer does. Privilege denying dude is a pretty good example of mansplaining:

knowyourmeme.com

The "not all men" interruption could be considered a subset of mansplaining, because it attempts to redirect a current conversation in a way that privileges mens' perspectives over women's. Also, like mansplaining, it's rude.

6) How does "Not All Men" fit into the history of feminism?

"Not all men" is just the latest iteration in a long tradition of feminists pointing out the ways in which language can be used by men to defend practices that benefit them and harm women.

"The very semantics of the language reflects [women's] condition. We do not even have our own names, but bear that of the father until we change it for that of a husband," the second-wave feminist activist Robin Morgan wrote in her book Going Too Far. She cited seemingly innocuous examples of sexism in language with words like "chairman" and "spokesman," and problematic language differences like a single male being called a "bachelor" while a single woman is called a "spinster" ("bachelorette" was only coined in the 20th century, while "spinster" and "bachelor" are both from the 14th century). The way we think and deal with gender gets expressed in language — and that includes, say, interrupting someone with a corrective "not all men."

Some analysts, like Sara Mills, have drawn a distinction between two forms of sexist language: overt and indirect. Overt sexism is embodied in hate speech, when a person is actively trying to hurt someone because of their gender. Indirect sexism includes things like gender stereotypes, misogynistic humor, and conversation diversion. Mills argues that overt sexism has been driven underground, only to create an environment where indirect sexism flourishes. And derailing tactics like "Not all men" are a prime example of indirectly sexist language.

Unfortunately, identifying indirect sexism in practice is hardly enough to stop it. When asked how the "Not all men" phenomenon has influenced her conversations on the internet about sexism, Hudson said that it hasn't. "I can't even talk about sexism without this ridiculous interrupting," she said.

7) So what can I do?

You can not interrupt, because interrupting is rude, and use that time instead to think about whether or not injecting "not all men" is going to derail a productive conversation.

You can also try making a "Not all men" joke with your favorite pop cultural shows like "Not all Aquamen":

flamingatheist.tumblr.com

flamingatheist.tumblr.com

"Not all men" Adventure Time:

Pia Glenn even made a "Not all men" Game of Thrones: