The Day The Online Music Died: How Popularity Doomed Streaming Darlings East Village Radio | Fast Company | Business + Innovation

If you build it, then attract enough users, the money will come.

That’s more or less the premise of scores of startups in the digital age--from Facebook to Twitter, Instagram to Snapchat.

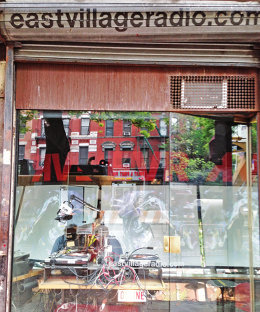

But what if that’s not always the case? What if monetizing or attracting a buyer--to say nothing of mere survival--is more complicated than that? In late May the online radio station East Village Radio shut down--taking its famous glass-walled street-level studio with it. The station, its renegade founders say, had gotten too popular to survive.

With over 1 million listeners and counting, EVR sure didn’t appear to be failing. But in today’s complicated Internet radio landscape, larger companies like Pandora--which just said it accounts for over 9% of all U.S. radio listening--and Spotify (with subscription models, unlike EVR) can afford to keep attracting more listeners. With each additional EVR fan, meanwhile, came something harder for a scrappy startup to manage: steeper royalty fees.

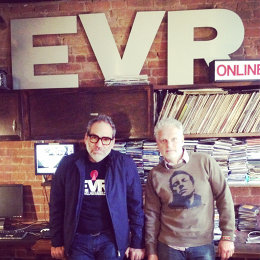

Frank Prisinzano and Peter Ferraro

Frank Prisinzano and Peter FerraroFor music services on the Internet, the cost of acquiring and maintaining a listener and building an engaged fan base is much higher than in that of consumer tech companies like Facebook, Twitter, and Pinterest. Music comes with rights attached, and those creating even the best of online experiences have to think--and pay--beyond just investors.

“We knew that no matter the projections, it wasn’t going to give us the infrastructure we needed to properly run the station,” says EVR's erstwhile general manager Peter Ferraro. “We would need seven figures to operate and compete, and that’s a lot of money.”

EVR wasn’t your typical Internet radio station. Started in June 2003 by Frank Prisinzano and joined later by Ferraro, both East Village residents, EVR championed up-and-coming artists, fostered collaborations, and pushed record sales hard. Inspired by WLIR, WPLJ, and other OAR stations in Queens and Long Island, Prisinzano and Ferraro, Italian Americans who bonded over their love of bands including Blue Oyster Cult, Talking Heads, The Who, The Ramones, and artists like Marvin Gaye, built EVR to help continue the culture of music discovery they experienced growing up in 1970s and 1980s New York City.

For them, this wasn’t just about asserting their cultural and taste-making relevance; it was about helping artists grow and build careers in an industry crumbling all around them. Industry leaders, labels, and fans listened. There were some 50 DJs playing music for more than 16 hours every day. Artists ranging from Peter Hook of Joy Division and New Order, to Amy Winehouse, to recent favorites including Disclosure would come for quick interviews, and end up staying for an hour. EVR was like a second home. And it wasn’t out of the ordinary to hear that tourists from Japan or Germany would come to shops in the East Village, thanks to hearing about them on EVR.

“We took it seriously,” said Ferraro. “We were committed to seven days a week, 24/7. In the beginning, it was about protecting the stream. In the early days, we never had a consistent stream in Internet radio. Throughout the years, three of us had the jobs of 15 people.”

Prisinzano and Ferraro grew the station first with that elusive, intangible talent: taste.

“People knew we played stuff that others didn’t, and it was cool,” says Prisinzano.

Next they leaned on tools that are more quantifiable, relying on social media to spread the station’s gospel.

The duo took especially quickly to Twitter, where they admit they sometimes act like two teenagers.

“We never wanted to change the music business,” Ferraro says. “We understood that artists create, and that they also need to promote and sell. We were the platform by which they could reach an audience and do just that."

All of which sounds like a recipe for a sustainable business. But here’s where things get complicated.

That’s partly because royalty calculation makes James Joyce look like Dr. Suess. Take a spin through The American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers site, and you’ll come across a page with directions for calculating what is owed. A royalty can vary greatly, depending on different values based on type of performance, the licensee’s heft (determined by the type of station playing the content), payments to the writers and publishers of said content, and more errata.

“We paid SoundExchange, ASCAP, BMI, SESAC, and others," says Ferraro. "As for SoundExchange, which terrestrial radio doesn't pay, we were paying 23 cents per every 100 listeners. As we gained more listeners we had to pay more.”

EVR had come smack up against a vexing problem--a paradox of popularity in this industry.

“The current system and SoundExchange royalty agreement punishes success," says Ken Freedman, General Manager for terrestrial and digital independent freeform radio station WFMU in New York. "It’s only sustainable if you have a very small audience. In other words, local taste-making has to stay under the radar.”

For its part, WFMU has had to be creative in order to survive.

“Since we became Corporation of Public Broadcasting qualified, we’ve been able to participate in group-negotiated rates for royalty fees," notes Freedman. "But for 10 years, we collected lots of waivers from record labels and artists, giving us permission to use their music [for free], similar to what Sirius XM has done.”

As it happens, the FCC is currently mulling over a ”wide-ranging proceeding on the current music licensing regime and whether reforms are necessary or appropriate,” according to the Broadcast Law blog. Holding roundtables in music hotbeds New York, Los Angeles, and Nashville, the FCC is looking to engage those in the industry in order to reimagine the current system. To hear Prisinzano and Ferraro tell it, their lawyer did not think the FCC pendulum would swing in a positive and sustainable direction for Internet broadcasters.

For EVR and its million fans--many of whom often made the trek to First Avenue to gawk at and cheer for DJs live on air--what makes all this even harder to swallow is the fact that the station was projected to do better financially this year than last year.

Since EVR’s collapse, music junkies have gone through a few stages of grief. And Prisinzano and Ferraro say they were thrilled to see “an incredible outpouring of support.”

Now fans are finding positive ways to spin the news. Nico Perez, founder of Mixcloud, the service that allows DJs to get their shows in front of listeners, says he thinks “the future of music discovery will be mostly through people, but also with some intelligent algorithms."

Perez is doing his part to ensure that while EVR might be dead, it won’t be forgotten. His company has offered to host the robust EVR archive at no charge.

"Hopefully there will be a legacy and a chance for future listeners to discover their archive," Perez says. (Ferraro says he isn't sure if any of the DJs will take Perez up on the offer, and some have already found other platforms for their shows.)

For those that haven’t discovered the station yet, Spotify users are creating a range of EVR playlists.

“It was a real honor to host at EVR and do my part to share a slice of downtown life with a global audience,” Daniel Glass, owner of the respected New York music label Glassnote music tells me. “They attracted great curators and DJs who gave the world a literal window into New York City life.”

Now the question is, will there be life after death for Prisinzano and Ferraro. Prisinzano owns a handful of successful East Village restaurants--which helped fund EVR--will continue innovating in the food industry, while looking for the next big idea.

Ferraro isn’t yet talking about his next move, but is certain he won’t leave music behind.

One thing is sure for both men: whatever they do next, they want to do it in the East Village. A note on the EVR homepage says: "Coming soon: a blog for the East Village."

And while this particular dream has died, the legacy is secure: when it comes to discovery, algorithms are great, but taste still matters.