Tetrodotoxin Poisoning Outbreak from Imported Dried Puffer Fish — Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2014

Jon B. Cole, MD1,2, William G. Heegaard, MD2, Jonathan R. Deeds, PhD3, Sara C. McGrath, PhD3, Sara M. Handy, PhD3 (Author affiliations at end of text)

On June 13, 2014, two patients went to the Hennepin County Medical Center Emergency Department in Minneapolis, Minnesota, with symptoms suggestive of tetrodotoxin poisoning (i.e., oral paresthesias, weakness, and dyspnea) after consuming dried puffer fish (also known as globefish) purchased during a recent visit to New York City. The patients said two friends who consumed the same fish had similar, although less pronounced, symptoms and had not sought care. The Minnesota Department of Health conducted an investigation to determine the source of the product and samples were sent to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition for chemical and genetic analysis. Genetic analysis identified the product as puffer fish (Lagocephalus lunaris) and chemical analysis determined it was contaminated with high levels of tetrodotoxin. A traceback investigation was unable to determine the original source of the product. Tetrodotoxin is a deadly, potent poison; the minimum lethal dose in an adult human is estimated to be 2–3 mg (1). Tetrodotoxin is a heat-stable and acid-stable, nonprotein, alkaloid toxin found in many species of the fish family Tetraodontidae (puffer fish) as well as in certain gobies, amphibians, invertebrates, and the blue-ringed octopus (2). Tetrodotoxin exerts its effects by blocking voltage-activated sodium channels, terminating nerve conduction and muscle action potentials, leading to progressive paralysis and, in extreme cases, to death from respiratory failure. Because these fish were reportedly purchased in the United States, they pose a substantial U.S. public health hazard given the potency of the toxin and the high levels of toxin found in the fish.

Case Reports

Patient 1. A man aged 30 years went to the emergency department (ED) with his sister (patient 2), concerned that they both might have puffer fish poisoning. The patient stated that he had purchased dried fish described as globefish from a street vendor in New York City and transported the fish to Minnesota himself. Six hours before he came to the ED, he rehydrated some fish and consumed it with his sister and two friends. Thirty minutes after consumption, he experienced perioral and tongue numbness, numbness and weakness in his extremities, extreme fatigue, and dyspnea. He also complained that "my teeth can't feel themselves." Despite self-induced vomiting, his symptoms did not resolve, after which he went to the ED. He noted that his two friends, who also consumed the fish but did not go to the ED, had similar symptoms that resolved over several hours.

At the ED, his temperature was 98.1°F (36.7°C), pulse 75 beats/min, respiratory rate 24 breaths/min, blood pressure 160/87 mmHg, and blood oxygen saturation 100% on room air. Physical examination was unremarkable; respiratory effort, mental status, and strength testing were normal. The patient was observed in the ED for 6 hours, during which time his hypertension and tachypnea resolved and his symptoms improved. Laboratory results were as follows: hemoglobin, 15.8 g/dL (normal range = 13.1–17.5), white blood cell count, 9,020/µL (normal = 4,000–10,000), platelets 221,000 (normal = 150,000–400,000), sodium 138 mEq/L (normal = 135–148), potassium 3.4 mEq/L (normal = 3.5–5.3), chloride 100 mEq/L (normal = 100–108), carbon dioxide 27 mEq/L (normal = 22–30), creatinine 0.66 mg/dL (normal = 0.7–1.25), ionized calcium, 4.68 mg/dL (normal = 4.4–5.2). Overnight observation was recommended; however, the patient elected to leave against medical advice.

Patient 2: A woman aged 33 years, who went to the ED with her brother (patient 1), also consumed the fish 6 hours before arrival at the ED and also complained of perioral and tongue numbness, numbness and weakness in her extremities, extreme fatigue, dyspnea, and the feeling that "my teeth can't feel themselves," all beginning 30 minutes after consuming the rehydrated fish. Her temperature was 98.1°F (36.7°C), pulse 71 beats/min, respiratory rate 16 breaths/min, blood pressure 110/74 mmHg, and blood oxygen saturation 100% on room air. Her physical examamination was unremarkable; respiratory effort, mental status, and strength testing were normal.

Laboratory results were as follows: hemoglobin, 14.4 g/dL (normal range = 13.1–17.5), white blood cell count, 6,080/µL (normal = 4,000–10,000), platelets 179,000/µL (normal = 150,000–400,000), sodium 141 mEq/L (normal = 135–148), potassium 3.6 mEq/L (normal = 3.5–5.3), chloride 105 mEq/L (normal = 100–108), carbon dioxide 29 mEq/L (normal = 22–30), creatinine 0.57 mg/dL (normal = 0.7–1.25), and ionized calcium, 4.9 mg/dL (normal = 4.4–5.2). After 6 hours of observation in the ED, the patient's symptoms began to improve. Overnight observation was recommended but she also left against medical advice.

Laboratory Analysis

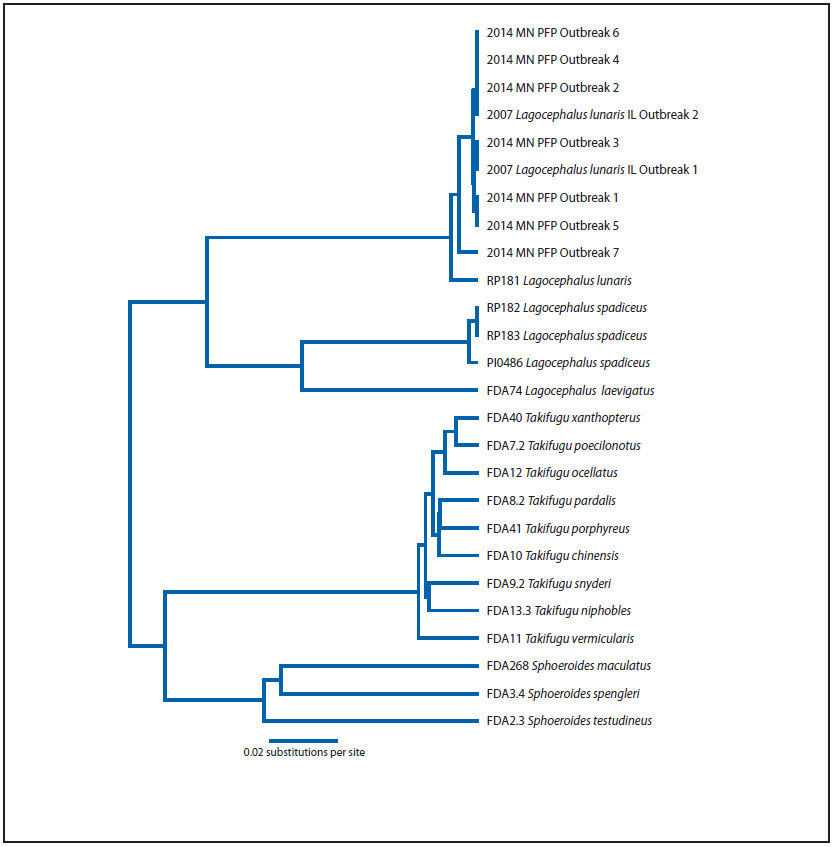

Seven of the dried, dressed fish (Figure 1) purchased by patient 1 were provided to the ED staff by the patients on arrival. Samples were transferred to the FDA Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition for analysis. Samples of dried muscle (10 mg) were taken from each fish for genetic analysis. A portion of the cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) mitochondrial gene was amplified and compared with COI sequences from FDA-authenticated reference standards for various species of puffer fish (3). The genetic analysis determined that all samples were Lagocephalus lunaris (Figure 2). For the toxin analysis, samples of dried muscle (2 g) were taken from each fish and rehydrated overnight at 39.2°F (4.0°C) using 10 mL of 1% acetic acid in water. After rehydration, tissues were homogenized, centrifuged, decanted, and samples were extracted a second time with an additional 9 mL of 1% acetic acid in water. Combined extracts were brought up to a total volume of 20 mL. Aliquots of each extract (2 mL) were de-fatted with 8 mL of chloroform, filtered (0.22 µm) and diluted 1:200 using 50/50 acetonitrile/1% acetic acid in water.

Samples were analyzed for tetrodotoxin by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-multiple reaction monitoring mass spectrometry (4). All seven samples were found to contain significant concentrations of tetrodotoxin with a mean of 19.8 ppm and a range of 5.7–72.3 ppm (Table). FDA has not established a guidance level for tetrodotoxin, but for comparison, the guidance level for the paralytic shellfish toxin saxitoxin, another alkaloid toxin with similar pharmacology and potency, is 0.8 ppm (5).

Actions Taken

Several attempts were made to contact patient 1 and patient 2 by telephone; however, none were successful. Visits to the two patients' home were made by both public health officials and law enforcement; however, current residents of the home stated that they had no knowledge of the patients' whereabouts. There was no labeling on the fish packaging, and all attempts to determine the source of the fish were unsuccessful. The Minnesota Department of Health and Department of Agriculture notified the New York City Department of Health and Department of Agriculture of the outbreak. However, with no specific information available about the source of the fish, no further investigation was feasible.

Discussion

The puffer fish (sometimes called globefish, fugu, or blowfish) is highly prized in many Asian cultures and is consumed safely in some countries (e.g., Japan). Consumption is safe, however, only with specialized training regarding which species to prepare and how to prepare them because the concentration and tissue distribution of toxin varies greatly among the >180 known species. Regulatory authorities in the United States do not provide this training, nor is tetrodotoxin testing routinely conducted; therefore, only the frozen meat, skin, and male gonad from one species of puffer fish (Takifugu rubripes) from Japan, processed according to Japanese safety guidelines, is permitted to be imported into the United States a limited number of times per year, pursuant to an FDA/Japanese government agreement established in 1988 (6). All other imported puffer fish products are prohibited (7). For domestic sources of puffer fish, only nontoxic species are recommended by FDA for consumption.* FDA regulates domestically sourced puffer fish through the Seafood Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points regulation (5). Selected states have established additional requirements for controls for puffer fish from certain areas because of potential toxicity (8).

Lagocephalus lunaris is an Indo-Pacific species of puffer fish and is one of the only species known to contain high concentrations of tetrodotoxin naturally in the meat, making safe preparation of this product impossible (9). In its native region, it has been confused with similar looking, nontoxic species, resulting in numerous illnesses (10). This is the same species that was illegally imported and responsible for illnesses in California, Illinois, and New Jersey in 2007 (4).

The presence of this puffer fish species in a U.S. market represents a substantial public health threat given the potentially lethal toxin and the high concentration of the toxin in the flesh of these fish. However, because the two patients provided limited information, the source of the fish and how it was imported, in violation of current FDA import restrictions, could not be determined. Medical professionals who work in EDs or with persons from countries with a tradition of puffer fish consumption should be aware of this potential public health threat and collaborate with local poison centers and health departments to investigate any outbreaks of tetrodotoxin poisoning to determine the source of the product and block additional sales to prevent additional illnesses. FDA recently released materials, including instructions for the collection and submission of meal remnants, for several fish-related illnesses, including puffer fish poisoning. These materials are available on CDC's Epidemic Information Exchange.†

Acknowledgments

Minnesota Department of Health; Minnesota Department of Agriculture; Roseville, Minnesota, Police Department.

1Hennepin Regional Poison Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota; 2Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota; 3Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Food and Drug Administration (Corresponding author: Jonathan R. Deeds, jonathan.deeds@fda.hhs.gov, 240-402-1474)

References

- Noguchi T, Ebesu JSM. Puffer poisoning: epidemiology and treatment. J Toxicol Toxin Rev 2001;20:1–10.

- Cavazzoni E, Lister B, Sargent P, Schibler A. Blue-ringed octopus (Hapalochlaena sp.) envenomation of a 4-year-old boy: a case report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2008;46:760–1.

- Handy SM, Deeds JR, Ivanova NV, et al. A single laboratory validated method for the generation of DNA barcodes for the identification of fish for regulatory compliance. J AOAC Int 2011;94:201–10.

- Cohen NJ, Deeds JR, Wong ES, et al. Public health response to puffer fish (tetrodotoxin) poisoning from mislabeled product. J Food Prot 2009;72:810–7.

- Food and Drug Administration. Fish and fisheries products hazards and controls guidance. 4th ed. US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration; 2014. Available at http://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/Seafood/ucm2018426.htm.

- Food and Drug Administration. Exchange of letters between Japan and the US Food and Drug Administration regarding puffer fish. US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Available at http://www.fda.gov/InternationalPrograms/Agreements/MemorandaofUnderstanding/ucm107601.htm.

- Food and Drug Administration. Import alert no. 16-20: detention without physical examination of puffer fish and foods that contain puffer fish. US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration; 2014. Available at http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cms_ia/importalert_37.html.

- Deeds JR, White KD, Etheridge SM, Landsberg JH. Concentrations of saxitoxin and tetrodotoxin in three species of puffers from the Indian River Lagoon, Florida, the site of multiple cases of saxitoxin puffer fish poisoning from 2002–2004. Trans Am Fish Soc 2008;137:1317–26.

- Yang CC, Liao SC, Deng JF. Tetrodotoxin poisoning in Taiwan: an analysis of poison center data. Vet Hum Toxicol 1996;38:282–6.

- Hwang DF, Hsieh YW, Shiu YC, Chen SK, Cheng CA. Identification of tetrodotoxin and fish species in a dried dressed fish fillet implicated in food poisoning. J Food Prot 2002;65:389–92.

What is already known on this topic?

The puffer fish (family Tetraodontidae; also known as globefish, fugu, or blowfish) is considered a delicacy in many parts of the world. Certain species of puffer fish naturally contain levels of the alkaloid toxin tetrodotoxin that are harmful to humans, requiring specialized training on safe methods of preparation and knowledge of which species can be safely consumed. Because of the risks, the importation of puffer fish products into the United States is highly restricted by the Food and Drug Administration.

What is added by this report?

Four cases of puffer fish poisoning in Minneapolis, Minnesota, resulted from consumption of dried globefish. Toxin analysis showed the product to be highly contaminated with tetrodotoxin, and a DNA analysis identified the fish as Lagocephalus lunaris, which is not allowed for import because naturally occurring toxin in its meat make safe preparation of this species impossible. Lack of product labeling and limited information provided by two persons who went to the emergency department prevented determination of the exact source of the product and how it was illegally imported into the country.

What are the implications for public health practice?

The presence of Lagocephalus lunaris in a U.S. market represents a public health threat given the potential lethal nature of the toxin and the high concentration of the toxin in the meat of these fish. Health care providers who work in emergency departments or with persons from countries with a tradition of puffer fish consumption should be aware of this potential public health threat and coordinate with local poison centers and health departments to investigate any suspected cases of puffer fish poisoning to determine the source of the fish, whether it was legally imported, and whether additional contaminated product needs to be removed from commerce.

FIGURE 1. Dried, dressed fillets of puffer fish (Lagocephalus lunaris) obtained from patients in a tetrodotoxin poisoning outbreak — Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2014

Alternate Text: The figure above is a photograph of dried, dressed fillets of puffer fish (Lagocephalus lunaris) obtained from patients in a tetrodotoxin poisoning outbreak in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 2014.

FIGURE 2. Genetic analysis* of dried puffer fish samples involved in a tetrodotoxin poisoning outbreak — Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2014

Abbreviations: MN = Minnesota; PFP = puffer fish poisoning; IL = Illinois; FDA = Food and Drug Administration.

Alternate Text: The figure above is an unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) tree showing the genetic analysis of dried puffer fish samples involved in a tetrodotoxin poisoning outbreak in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 2014. The genetic analysis determined that all samples were Lagocephalus lunaris.

Sample | Amount of toxin | Species identification |

Dried fish 1 | 7.7 ppm | Lagocephalus lunaris |

Dried fish 2 | 17.4 ppm | Lagocephalus lunaris |

Dried fish 3 | 16.1 ppm | Lagocephalus lunaris |

Dried fish 4 | 72.3 ppm | Lagocephalus lunaris |

Dried fish 5 | 12.4 ppm | Lagocephalus lunaris |

Dried fish 6 | 5.7 ppm | Lagocephalus lunaris |

Dried fish 7 | 6.7 ppm | Lagocephalus lunaris |

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices.

**Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.