How “omnipotent” hackers tied to NSA hid for 14 years—and were found at last | Ars Technica

Aurich Lawson

CANCUN, Mexico — In 2009, one or more prestigious researchers received a CD by mail that contained pictures and other materials from a recent scientific conference they attended in Houston. The scientists didn't know it then, but the disc also delivered a malicious payload developed by a highly advanced hacking operation that had been active since at least 2001. The CD, it seems, was tampered with on its way through the mail.

It wasn't the first time the operators—dubbed the "Equation Group" by researchers from Moscow-based Kaspersky Lab—had secretly intercepted a package in transit, booby-trapped its contents, and sent it to its intended destination. In 2002 or 2003, Equation Group members did something similar with an Oracle database installation CD in order to infect a different target with malware from the group's extensive library. (Kaspersky settled on the name Equation Group because of members' strong affinity for encryption algorithms, advanced obfuscation methods, and sophisticated techniques.)

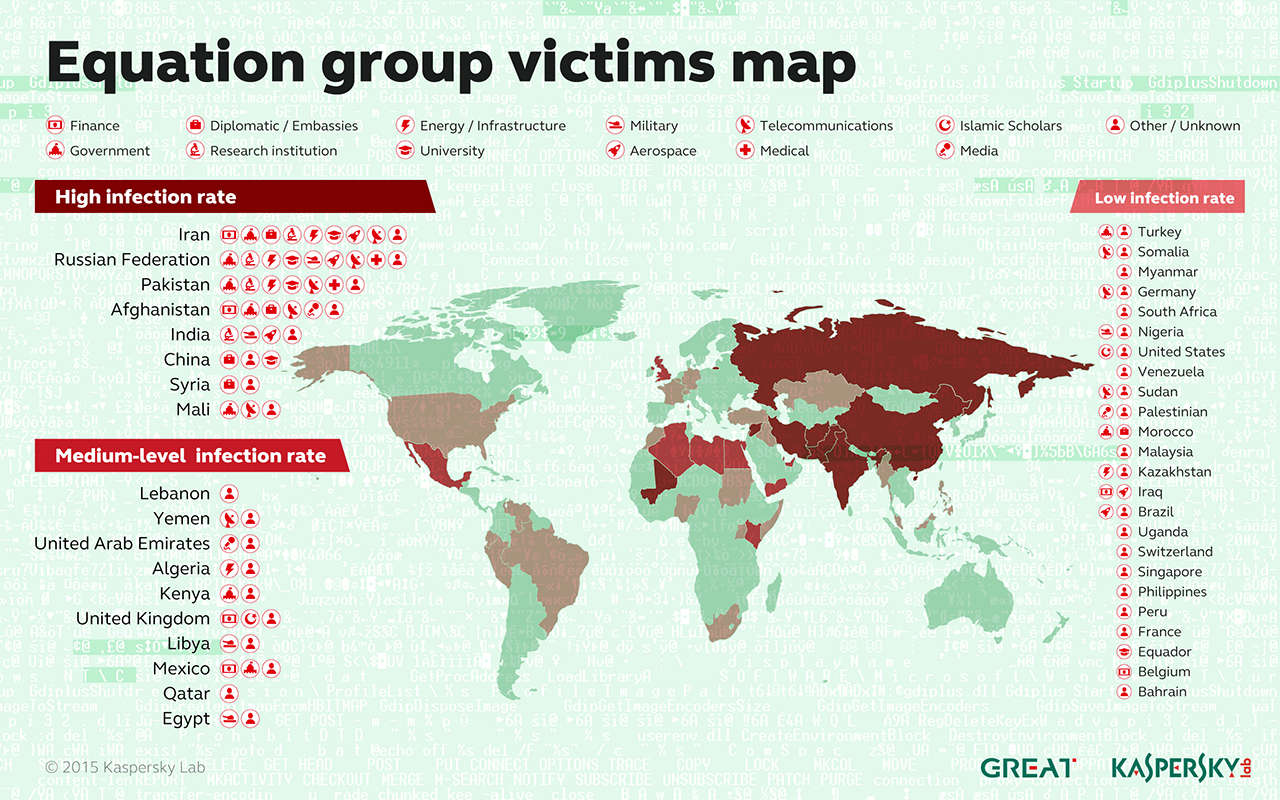

Kaspersky researchers have documented 500 infections by Equation Group in at least 42 countries, with Iran, Russia, Pakistan, Afghanistan, India, Syria, and Mali topping the list. Because of a self-destruct mechanism built into the malware, the researchers suspect that this is just a tiny percentage of the total; the actual number of victims likely reaches into the tens of thousands.

A long list of almost superhuman technical feats illustrate Equation Group's extraordinary skill, painstaking work, and unlimited resources. They include:

- The use of virtual file systems, a feature also found in the highly sophisticated Regin malware. Recently published documents provided by Ed Snowden indicate that the NSA used Regin to infect the partly state-owned Belgian firm Belgacom.

- The stashing of malicious files in multiple branches of an infected computer's registry. By encrypting all malicious files and storing them in multiple branches of a computer's Windows registry, the infection was impossible to detect using antivirus software.

- Redirects that sent iPhone users to unique exploit Web pages. In addition, infected machines reporting to Equation Group command servers identified themselves as Macs, an indication that the group successfully compromised both iOS and OS X devices.

- The use of more than 300 Internet domains and 100 servers to host a sprawling command and control infrastructure.

- USB stick-based reconnaissance malware to map air-gapped networks, which are so sensitive that they aren't connected to the Internet. Both Stuxnet and the related Flame malware platform also had the ability to bridge airgaps.

- An unusual if not truly novel way of bypassing code-signing restrictions in modern versions of Windows, which require that all third-party software interfacing with the operating system kernel be digitally signed by a recognized certificate authority. To circumvent this restriction, Equation Group malware exploited a known vulnerability in an already signed driver for CloneCD to achieve kernel-level code execution.

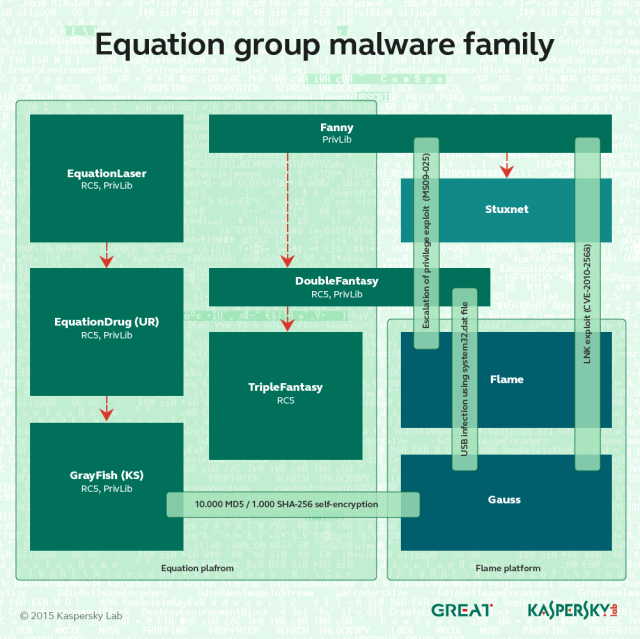

Taken together, the accomplishments led Kaspersky researchers to conclude that Equation Group is probably the most sophisticated computer attack group in the world, with technical skill and resources that rival the groups that developed Stuxnet and the Flame espionage malware.

"It seems to me Equation Group are the ones with the coolest toys," Costin Raiu, director of Kaspersky Lab's global research and analysis team, told Ars. "Every now and then they share them with the Stuxnet group and the Flame group, but they are originally available only to the Equation Group people. Equation Group are definitely the masters, and they are giving the others, maybe, bread crumbs. From time to time they are giving them some goodies to integrate into Stuxnet and Flame."

Further Reading

In an exhaustive report published Monday at the Kaspersky Security Analyst Summit here, researchers stopped short of saying Equation Group was the handiwork of the NSA—but they provided detailed evidence that strongly implicates the US spy agency.

First is the group's known aptitude for conducting interdictions, such as installing covert implant firmware in a Cisco Systems router as it moved through the mail.

Second, a highly advanced keylogger in the Equation Group library refers to itself as "Grok" in its source code. The reference seems eerily similar to a line published last March in an Intercept article headlined "How the NSA Plans to Infect 'Millions' of Computers with Malware." The article, which was based on Snowden-leaked documents, discussed an NSA-developed keylogger called Grok.

Third, other Equation Group source code makes reference to "STRAITACID" and "STRAITSHOOTER." The code words bear a striking resemblance to "STRAITBIZARRE," one of the most advanced malware platforms used by the NSA's Tailored Access Operations unit. Besides sharing the unconventional spelling "strait," Snowden-leaked documents note that STRAITBIZARRE could be turned into a disposable "shooter." In addition, the codename FOXACID belonged to the same NSA malware framework as the Grok keylogger.

Apart from these shared code words, the Equation Group in 2008 used four zero-day vulnerabilities—including two that were later incorporated into Stuxnet.

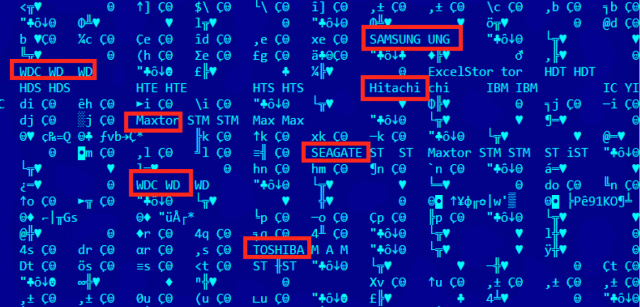

The similarities don't stop there. Equation Group malware dubbed GrayFish encrypted its payload with a 1,000-iteration hash of the target machine's unique NTFS object ID. The technique makes it impossible for researchers to access the final payload without possessing the raw disk image for each individual infected machine. The technique closely resembles one used to conceal a potentially potent warhead in Gauss, a piece of highly advanced malware that shared strong technical similarities with both Stuxnet and Flame. (Stuxnet, according to The New York Times, was a joint operation between the NSA and Israel, while Flame, according to The Washington Post, was devised by the NSA, the CIA, and the Israeli military.)Beyond the technical similarities to the Stuxnet and Flame developers, Equation Group boasted the type of extraordinary engineering skill people have come to expect from a spy organization sponsored by the world's wealthiest nation. One of the Equation Group's malware platforms, for instance, rewrote the hard-drive firmware of infected computers—a never-before-seen engineering marvel that worked on 12 drive categories from manufacturers including Western Digital, Maxtor, Samsung, IBM, Micron, Toshiba, and Seagate.

The malicious firmware created a secret storage vault that survived military-grade disk wiping and reformatting, making sensitive data stolen from victims available even after reformatting the drive and reinstalling the operating system. The firmware also provided programming interfaces that other code in Equation Group's sprawling malware library could access. Once a hard drive was compromised, the infection was impossible to detect or remove.

Enlarge/ Forensics software displays some of the hard drives Equation Group was able to commandeer using malicious firmware.

Enlarge/ Forensics software displays some of the hard drives Equation Group was able to commandeer using malicious firmware.Kaspersky Lab

While it's simple for end users to re-flash their hard drives using executable files provided by manufacturers, it's just about impossible for an outsider to reverse engineer a hard drive, read the existing firmware, and create malicious versions.

"This is an incredibly complicated thing that was achieved by these guys, and they didn't do it for one kind of hard drive brand," Raiu said. "It's very dangerous and bad because once a hard drive gets infected with this malicious payload it's impossible for anyone, especially an antivirus [provider], to scan inside that hard drive firmware. It's simply not possible to do that."

Kaspersky Lab