Facebook tips news balance 'less than users do' - BBC News

Algorithms filter a lot of the content that we see on social media

Algorithms filter a lot of the content that we see on social media A study by Facebook's own researchers has investigated whether the site's "news feed" filters content that users disagree with politically.

It finds that Facebook's algorithms do sift out some challenging items - but this has a smaller effect than our own decisions to click (or not) on links.

By far the biggest hit to ideologically "cross-cutting" content comes from the selection of our Facebook friends.

Other experts welcomed the study but also called for more, broader research.

Published in the journal Science, the new study was motivated by the much-debated idea that getting our news via online social networks can isolate us from differing opinions.

Critics have argued that this effect, particularly if exacerbated by "social algorithms" that select clickable content for us, is bad for democracy and public debate.

"People are increasingly turning to their social networks for news and information," said co-author Solomon Messing, a data scientist at Facebook.

The choice of the articles that you select matters more than the news feed algorithmDr Solomon Messing, Facebook"We wanted to quantify the extent to which people are sharing ideologically diverse news content - and the extent to which people actually encounter and read it in social media."

Choices, choices

Dr Messing and his colleagues studied 10.1 million US Facebook users, drawn from the 9% of adults on the site who declare their political affiliation as part of their profile - labelling themselves "liberal" or "conservative", for example.

The researchers found 226,000 news stories that were shared by more than 20 of those users, and gave a political "alignment" score to each one based on the stated ideology of the people who shared it.

Then they set about evaluating how much "cross-cutting" content, from the opposing political sphere, was available to each user.

What are the dangers of using social networks to read the news?

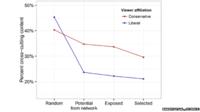

What are the dangers of using social networks to read the news? If people accessed random posts from right across Facebook, the study reports that 40-45% of what they saw would fall into that category. But, of course, this is not how the Facebook news feed works, because we only see what our friends share.

Based on what their friends posted on the site, the users in the study could only ever have seen a news feed with 29.5% cross-cutting material.

This is quite a drop, largely produced by our tendency to "friend" people similar to ourselves; the study reported that on average, about 80% of a user's Facebook friends, if they declare a preference, have similar political views.

After we select our own friends, Facebook also refines what we see in the news feed using its complicated, controversial - and confidential - social algorithms. According to the study, this process did cut the proportion of cross-cutting material down further, but only to 28.9%.

Then, even within what users were offered by their Facebook feed, the links from contrasting perspectives received fewer clicks: only 24.9% of the content people clicked or tapped was cross-cutting.

These percentages varied between the self-declared "conservative" and "liberal" Facebook populations, but the case made by the Facebook researchers is clear: "If you average over liberals and conservatives, you can very easily see that the choice of the articles that you select matters more than the news feed algorithm," Dr Messing told the BBC.

Percentages varied between the political groups, but challenging material was less common within users' networks than in a random sample across Facebook - and then the percentage dropped again within what they saw on their feed, and what they selected to click on

Percentages varied between the political groups, but challenging material was less common within users' networks than in a random sample across Facebook - and then the percentage dropped again within what they saw on their feed, and what they selected to click on But he agreed that our choice of online friends makes the biggest difference - and that, based on this study, reading news through that filter cuts out a lot of ideologically challenging material, relative to what is shared across Facebook.

There is a broader need for scientists to study these systems in a manner that is independent of the Facebooks of the worldDr David Lazer, Northeastern UniversityThe big, unanswered question is whether this places us in any more of an echo chamber than reading news directly from our favourite major media brands, or other sources we find for ourselves.

Vigilance required

In a commentary also published in Science, Dr David Lazer from Northeastern University in Boston said this was an awkward comparison: "It is not possible to determine definitively whether Facebook encourages or hinders political discussion across partisan divides relative to a pre-Facebook world, because we do not have nearly the same quality or quantity of data for the pre-Facebook world."

He also said this research topic was a crucial one, and "continued vigilance" would be required.

"Facebook deserves great credit... for conducting this research in a public way. But there is a broader need for scientists to study these systems in a manner that is independent of the Facebooks of the world."

Prof Mason Porter, a researcher at Oxford University, UK, who has also studied social networks, expressed similar sentiments.

"This is something that it's really important to try to disentangle," he told the BBC. He said the next step would be to compare the findings with what happens in other online environments.

"How much is this true in other social networks? The main thing for studies like this is that you want to repeat it in different ways. I think it's going to inspire a lot more studies, which is really one of the best things a scientific paper can do," Prof Porter said.

Many people, especially younger generations, get a lot of their news from social media

Many people, especially younger generations, get a lot of their news from social media Patrick Wolfe, a professor of statistics and computer science at University College London, said the study was interesting despite some limitations in the data.

"I think the claims are reasonably plausible; I don't think the conclusion is that surprising," Prof Wolfe told BBC News.

He commented that biases in how the subjects were selected might mean that the findings did not reflect the wider population. In particular, to get their 10 million users the researchers first excluded the 30% of US Facebook users who visit on fewer than four days each week - as well as the 91% of adult users who do not declare their political affiliation.

The authors agree their study is limited, but say these decisions were a matter of extracting something relevant from Facebook's vast reserves of data.

"We're interested in the population who are regular social media users," Dr Messing said. "For people who log on once a month, this question isn't really relevant."

And the numbers are still large: "We have millions of observations," he said. "The error bars are smaller than the points on the graph."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter