Idle Words about the amazon bomber algos

The piece claims that “users searching for a common chemical compound used in food production are offered the ingredients to produce explosive black powder” on Amazon’s website, and that “steel ball bearings often used as shrapnel” are also promoted on the page, in some cases as items that other customers also bought.

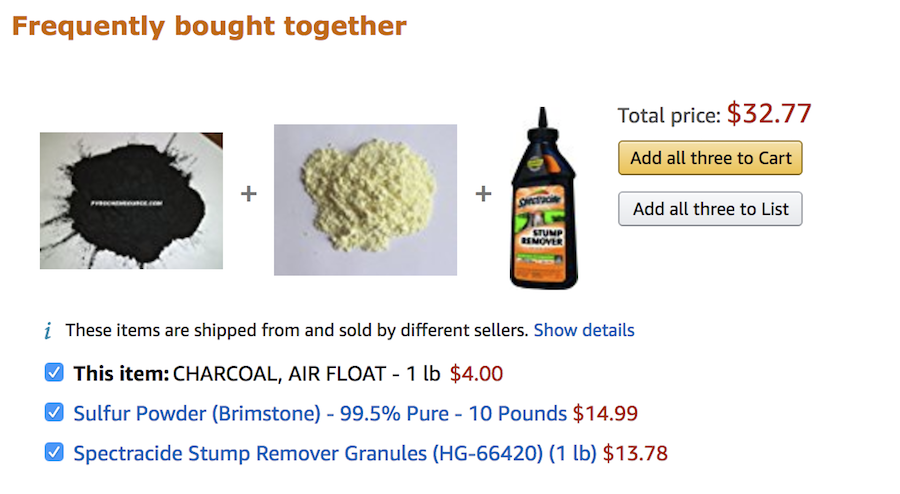

The ‘common chemical compound’ in Channel 4’s report is potassium nitrate, an ingredient used in curing meat. If you go to Amazon’s page to order a half-kilo bag of the stuff , you’ll see the suggested items include sulfur and charcoal, the other two ingredients of gunpowder. (Unlike Channel 4, I am comfortable revealing the secrets of this 1000-year-old technology.)

The implication is clear: home cooks are being radicalized by the site’s recommendation algorithm to abandon their corned beef in favor of shrapnel-packed homemade bombs. And more ominously, enough people must be buying these bomb parts on Amazon for the algorithm to have noticed the correlations, and begin making its dark suggestions.

But as a few more minutes of clicking would have shown, the only thing Channel 4 has discovered is a hobbyist community of people who mill their own black powder at home, safely and legally, for use in fireworks, model rockets, antique firearms, or to blow up the occasional stump.

It’s legal to make and possess black powder in the United Kingdom. There are limits on how much of the stuff you can have (100 grams), but because black powder is easy to make from cheap ingredients, hard to set off by accident, and not very toxic, it’s a popular choice for amateurs. All you need is a device called a ball mill , a rotating drum packed with ball bearings that mixes the powders together and grinds the particles to a uniform size.

And this leads us to the most spectacular assertion in the Channel 4 report, that along with sulfur and charcoal, Amazon’s algorithm is recommending detonators, cables, and "steel ball bearings often used as shrapnel in explosive devices."

The ball bearings Amazon is recommending are clearly intended for use in the ball mill. The algorithm is picking up on the fact that people who buy the ingredients for black powder also need to grind it. It's no more shocking than being offered a pepper mill when you buy peppercorns.

The idea that these ball bearings are being sold for shrapnel is a reporter's fantasy. There is no conceivable world in which enough bomb-making equipment is being sold on Amazon to train an algorithm to make this recommendation.

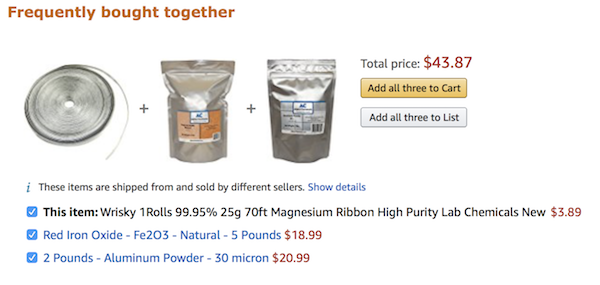

The Channel 4 piece goes on to reveal that people searching for ‘another widely available chemical’ are being offered the ingredients for thermite, a mixture of metal powders that when ignited “creates a hazardous reaction used in incendiary bombs and for cutting through steel.”

In this case, the ‘widely available chemical’ is magnesium ribbon. If you search for this ribbon on Amazon, the site will offer to sell you iron oxide (rust) and aluminum powder, which you can mix together to create a spectacular bit of fireworks called the thermite reaction:

The thermite reaction is performed in every high school chemistry classroom, as a fun reward for students who have had to suffer through a baffling unit on redox reactions. You mix the rust and powdered aluminum in a crucible, light them with the magnesium ribbon, and watch a jet of flame shoot out, leaving behind a small amount of molten iron. The mixed metal powders are hard to ignite (that’s why you need the magnesium ribbon), but once you get them going, they burn vigorously.

The main consumer use for thermite, as far as I can tell, is lab demonstrations and recreational chemistry. Importantly, thermite is not an explosive—it will not detonate.

So Channel 4 has discovered that fireworks enthusiasts and chemistry teachers shop on Amazon.

But by blending these innocent observations into an explosive tale of terrorism, they’ve guaranteed that their coverage will attract the maxmium amount of attention.

The ‘Amazon teaches bomb-making’ story has predictably spread all over the Internet:

Missing in these reports is any sense of proportion or realism. In what universe would an innocent person shopping for a bag of elemental sulfur be radicalized into making an improvised gunpowder bomb, complete with shrapnel, by a recommendations engine?

Does Channel 4 think that instructions for making explosives are hard to find online, so that people have to resort to hit-and-miss shopping for chemical elements to learn the secret of gunpowder?

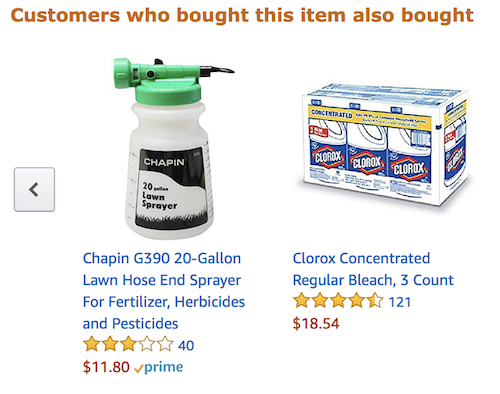

And how much duty of care does Amazon have in making product recommendations? The product page for household ammonia, for example, offers as a recommended item a six-pack of concentrated bleach. Ammonia and bleach react together to create a deadly gas, and you can buy both on Amazon in practically unlimited quantities. Does that mean Amazon is trying to persuade customers to poison people with chloramine?

Finally, just how many people does Channel 4 imagine are buying bombs online? For a recommendations algorithm to be suggesting shrapnel to sulfur shoppers implies that thousands or tens of thousands of people are putting these items together in their shopping cart. So where are all these black powder bombers? And why on earth would an aspiring bomber use an online shopping cart tied to their real identity?

A more responsible report would have clarified that black powder, a low-velocity explosive, is not a favored material for bomb making. Other combinations are just as easy to make, and pack a bigger punch.

The bomb that blew up the Federal building in Oklahoma City, for example, was a mixture of agricultural fertilizer and racing fuel. Terrorists behind the recent London bombings have favored a homemade explosive called TATP that can be easily synthesized from acetone, a ubiquitous industrial solvent.

Those bombers who do use black powder find it easier to just scrape it out of commercially available fireworks, which is how the Boston Marathon bomber obtained the explosives for his device. The only people carefully milling the stuff from scratch, after buying it online in an easily traceable way, are harmless musket owners and rocket nerds who will now face an additional level of hassle.

The shoddiness of this story has not prevented it from spreading like a weed to other media outlets, accumulating errors as it goes.

The New York Times omits the bogus shrapnel claim, but falsely describes thermite as “ two powders that explode when mixed together in the right proportions and then ignited.” (Thermite does not detonate.)

Vice repeats Channel 4’s unsubstantiated claims about ‘shrapnel’, while also implying that thermite is an explosive: “c omponents needed to make thermite, used in incendiary bombs, were paired with steel ball bearings (DIY shrapnel).”

The Independent is even more confused , reporting that “ i f users click on Thermite, for example, which is a pyrotechnic composition of metal powder, the website links to two other items.” It also puts the phrase ‘mother of Satan’ in the URL, presumably to improve the article’s search engine ranking for the unrelated explosive TATP.

Slate repeats Channel 4’s assertion that Amazon is nudging ‘ the customer to buy ball bearings, which can be used as shrapnel in homemade explosives.”

Only the skeptical BBC bothers to consult with outside experts , who correctly note that large numbers of people would have to be buying these items in combination to have any effect on the algorithm.

When I contacted the author of one of these pieces to express my concerns, they explained that the piece had been written on short deadline that morning, and they were already working on an unrelated article. The author cited coverage in other mainstream outlets (including the New York Times) as justification for republishing and not correcting the assertions made in the original Channel 4 report.

The real story in this mess is not the threat that algorithms pose to Amazon shoppers, but the threat that algorithms pose to journalism. By forcing reporters to optimize every story for clicks, not giving them time to check or contextualize their reporting, and requiring them to race to publish follow-on articles on every topic, the clickbait economics of online media encourage carelessness and drama. This is particularly true for technical topics outside the reporter’s area of expertise.

And reporters have no choice but to chase clicks. Because Google and Facebook have a duopoly on online advertising, the only measure of success in publishing is whether a story goes viral on social media. Authors are evaluated by how individual stories perform online, and face constant pressure to make them more arresting. Highly technical pieces are farmed out to junior freelancers working under strict time limits. Corrections, if they happen at all, are inserted quietly through ‘ninja edits’ after the fact.

There is no real penalty for making mistakes, but there is enormous pressure to frame stories in whatever way maximizes page views. Once those stories get picked up by rival news outlets, they become ineradicable. The sheer weight of copycat coverage creates the impression of legitimacy. As the old adage has it, a lie can get halfway around the world while the truth is pulling its boots on.

Earlier this year, when the Guardian published an equally ignorant (and far more harmful) scare piece about a popular secure messenger app, it took a group of security experts six months of cajoling and pressure to shame the site into amending its coverage. And the Guardian is a prestige publication, with an independent public editor. Not every story can get such editorial scrutiny on appeal, or attract the sympathetic attention of Teen Vogue.

The very machine learning systems that Channel 4’s article purports to expose are eroding online journalism’s ability to do its job.

Moral panics like this one are not just harmful to musket owners and model rocket builders. They distract and discredit journalists, making it harder to perform the essential function of serving as a check on the powerful.

The real story of machine learning is not how it promotes home bomb-making, but that it's being deployed at scale with minimal ethical oversight, in the service of a business model that relies entirely on psychological manipulation and mass surveillance. The capacity to manipulate people at scale is being sold to the highest bidder, and has infected every aspect of civic life, including democratic elections and journalism.

Together with climate change, this algorithmic takeover of the public sphere is the biggest news story of the early 21st century. We desperately need journalists to cover it. But as they grow more dependent on online publishing for their professional survival, their capacity to do this kind of reporting will disappear, if it has not disappeared already.