Self-Driving Cars Will Always Be Limited. Even the Industry Leader Admits it.

Don’t believe me? Listen to the CEO of Waymo.

How quickly perceptions can change. It may seem hard to remember now, but a year ago the hype machine was still full steam ahead on self-driving cars and their presumed future dominance of the transportation system. Cars weren’t going anywhere, many presumed, but drivers would be liberated as software took over their role, making everyone a passenger.

The fatal Uber crash hadn’t happened. People still believed that Tesla’s Autopilot system was safe and that Full Self-Driving was on the horizon. There was little question in the reporting on autonomous vehicles that they were safer than human drivers, despite the complete lack of evidence. The tech visionaries had spoken, and as is too often the case, the media fell in line.

However, around the turn of the new year, criticism of the previous optimism was emerging. In January, I was among those pointing to the delayed timelines, growing number of collisions, and the slowing progress in reducing the number of times that human test drivers had to take over from the computers. As the year has played out, critics have been proven right, and a much more inspiring vision for the future of transportation has emerged.

The Decline of the Self-Driving Car

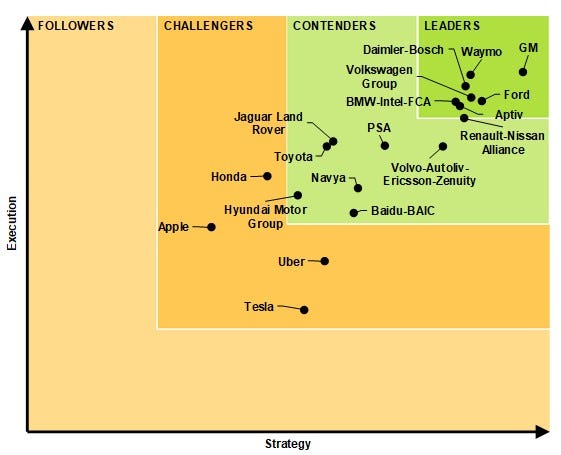

Waymo, a division of Alphabet, has long been acknowledged as the leader in autonomous vehicle technology. Based on the limited data that’s been released, its vehicles are acknowledged as having driven the most miles in self-driving mode and have the lowest rate of disengagements (when humans have to take over).

Waymo CEO John Krafcik. Source: Waymo

Waymo CEO John Krafcik. Source: Waymo

However, even Waymo’s CEO, John Krafcik, now admits that the self-driving car that can drive in any condition, on any road, without ever needing a human to take control — what’s usually called a “level 5” autonomous vehicle — will never exist. At the Wall Street Journal’s D.Live conference on November 13, Krafcik said that “autonomy will always have constraints.” It will take decades for self-driving cars to become common on roads, and even then they will not be able to drive in certain conditions, at certain times of the year, or in any weather. In short, sensors on autonomous vehicles don’t work well in snow or rain — and that may never change.

It’s still surprising to hear such a statement by someone leading a self-driving vehicle company, but given what has happened throughout 2018, it shouldn’t be. There were a number of negative stories about self-driving cars through the year, including more deaths of people using Tesla’s Autopilot technology, but the effect of an Uber self-driving car killing a woman with her bike in Tempe, Arizona in March cannot be understated. That singular event broke through the largely uncritical mainstream coverage of autonomous vehicles and showed how far the technology really had to go before it would really be safe — if it ever could be.

The initial event was bad enough: a self-driving car failing to slow down to avoid hitting a person and a safety driver that was too distracted to notice. But as the National Transportation Safety Board investigated the incident, it emerged that the autonomous driving system was unable to identify that the object in front of it was a person, and that when it finally did correctly identify that it had to stop — just 1.3 seconds before impact — it couldn’t because emergency braking had been disabled and there was no way to alert the safety driver to the problem. In addition, leaks showed that Uber safety drivers had to intervene every 13 miles (21 km) compared to ever 5,600 miles (9,000 km) on average for Waymo’s vehicles, and the team was putting their test vehicles in unsafe situations to try to hit impossible deadlines. It was a complete mess, and eventually blew up Uber’s future plans that were, in part, depending on autonomous vehicles to reduce labor costs by displacing human drivers.

Source: Navigant Research

Source: Navigant Research

Uber had to completely halt its autonomous vehicle testing, despite already being far behind its competitors. It pulled out of Arizona completely, laid off most of its safety drivers, and only reapplied to resume testing in Pittsburgh at the beginning of November — almost eight months after the fatal crash. But between March and November, everything changed. No longer does anyone credibly claim that self-driving cars are the future of transportation, and Uber has even shifted its focus to scooters, e-bikes, and turning its app into the “Amazon for transportation.”

At the beginning of the year, it would have been unimaginable for the CEO of Waymo to publicly acknowledge that self-driving cars will never work in all conditions. Now, it’s a statement of fact that anyone familiar with the industry already knows. But while the hype about self-driving cars is over, there’s a new vision for urban transportation that’s much more inspiring than letting automobiles continue to dominate our streets — and everyone wants in.

The Coming Transportation Revolution?

A year ago, it seemed like the future of transportation would simply be the present, augmented with a bit more tech, but that no longer seems to be the case. It’s not surprising to hear that European cities are improving transit, adding bikes lanes, and taking space away from cars, but that’s also becoming more common in American cities.

And why shouldn’t it? Yes, cities in the United States are still overwhelmingly dominated by cars, but that doesn’t mean they always have to be — remember, there was a time before the automobile. Millennials drive less than other generations and a recent survey showed that 51 percent of them “do not believe that owning a car is worth the investment.” Instead of driving, millennials want better public transit and more options to bike and walk around their cities — and they’re getting them.

Over the past year and a half, dockless e-bikes and scooters — also called “micromobility” — landed on the sidewalks of cities around the country. Initially, there was backlash — these bikes and scooters were on roads previously reserved for cars, but more importantly they were imposing on the very limited space allotted to pedestrians. However, city governments weren’t slow to act like they were when Uber and Lyft rolled out their ride-hailing services.

Local governments have reacted with a range of regulations to cap the number of bikes and scooters, set speed limits and off-limit zones, and some have even started turning some on-street car parking spaces in micromobility parking. Even more importantly, governments have access to bike and scooter trip data, and as more people use them, the pressure to add more bike lanes and improve micromobility infrastructure grows.

In urban planning, there’s a concept called induced demand which says that when the supply of a good increases, so will its demand. This is typically applied to roads and explains why even when highways are widened, congestion rarely improves: the additional lanes simply attract more drivers. However, the same is happening with micromobility. As dockless bikes and scooters are added to cities, they’re creating demand that didn’t previously exist. New cyclists and scooter users then create pressure for better parking and bike lanes, which results in a positive feedback loop by attracting more users, who create more pressure for infrastructure, and on and on. In the past, the feedback loop has benefited drivers, but momentum may finally be shifting to more active forms of mobility.

American cities have been dominated by cars for decades, to the point where it can be difficult for people who grew up in them to imagine anything else. But millennials are demanding a different kind of city and better ways of moving around them than their parents wanted. Young people are more likely to want to live close to the core, not in a far-flung suburb, and they want to take the subway, the bus, or a bike instead of being stuck in their car.

For boomers, the car was a symbol of freedom that allowed them to hit the open road and go wherever they wanted — but many of their children don’t feel the same. Instead, millennials see cars as an expensive inconvenience; wages are lower, vehicle costs are higher, and they’d rather just get where they’re going than having to wait in traffic and circle for ages to find parking. The self-driving car was a reflection of the future imagined by car-loving boomers, but micromobility is the future that millennials want — and the one that has the best chance of succeeding.