Twenty-fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution - Wikipedia

The Twenty-fifth Amendment (Amendment XXV) to the United States Constitution deals with issues related to presidential succession and disability. It clarifies that the Vice President becomes President (as opposed to Acting President) if the president dies, resigns, or is removed from office; and establishes procedures for filling a vacancy in the office of the vice president and for responding to presidential disabilities.[1] The Twenty-fifth Amendment was submitted to the states on July 6, 1965, by the 89th Congress and was adopted on February 10, 1967.[2]

Text and effect [ edit ]

Article II, Section 1, Clause 6 of the Constitution reads:

In Case of the Removal of the President from Office, or of his Death, Resignation, or Inability to discharge the Powers and Duties of the said Office, the Same shall devolve on the Vice President ...

This provision is ambiguous as to whether, in the enumerated circumstances, the vice president becomes the president, or merely assumes the "powers and duties" of the presidency. It also fails to define what constitutes inability, or how questions concerning inability are to be resolved.[3] The Twenty-fifth Amendment addresses these deficiencies.

Section 1: Presidential succession [ edit ]

Section 1. In case of the removal of the President from office or of his death or resignation, the Vice President shall become President.

Section 1 clarifies that in the enumerated situations the vice president becomes president, instead of merely assuming the powers and duties of the presidency.

Section 2: Vice presidential vacancy [ edit ]

Section 2. Whenever there is a vacancy in the office of the Vice President, the President shall nominate a Vice President who shall take office upon confirmation by a majority vote of both Houses of Congress.

Section 2 addresses the Constitution's original failure to provide a mechanism for filling a vacancy in the office of vice president. The vice presidency had become vacant several times due to death, resignation, or succession to the presidency, and these vacancies had often lasted several years.

Section 3: Presidential declaration [ edit ]

Section 3. Whenever the President transmits to the

President pro tempore of the Senateand the

Speaker of the House of Representativeshis written declaration that he is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, and until he transmits to them a written declaration to the contrary, such powers and duties shall be discharged by the Vice President as Acting President.

Section 3 allows the president to voluntarily transfer his authority to the vice president (for example, in anticipation of a medical procedure) by declaring in writing his inability to discharge his duties. The vice president then assumes the powers and duties of the presidency as acting president; the vice president does not become president and the president remains in office, although without authority. The president regains his powers and duties when he declares in writing that he is again ready to discharge them.[4]

Section 4: Declaration by vice president and principal officers [ edit ]

Section 4. Whenever the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers of the executive departments or of such other body as Congress may by law provide, transmit to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives their written declaration that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, the Vice President shall immediately assume the powers and duties of the office as Acting President.

Thereafter, when the President transmits to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives his written declaration that no inability exists, he shall resume the powers and duties of his office unless the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers of the executive department or of such other body as Congress may by law provide, transmit within four days to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives their written declaration that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office. Thereupon Congress shall decide the issue, assembling within forty-eight hours for that purpose if not in session. If the Congress, within twenty-one days after receipt of the latter written declaration, or, if Congress is not in session, within twenty-one days after Congress is required to assemble, determines by two-thirds vote of both Houses that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, the Vice President shall continue to discharge the same as Acting President; otherwise, the President shall resume the powers and duties of his office.

[5]Section 4 addresses the case of an incapacitated president who is unable or unwilling to execute the voluntary declaration contemplated in Section 3; it is the amendment's only section that has never been invoked. It allows the vice president, together with a "majority of either the principal officers of the executive departments or of such other body as Congress may by law provide," to declare the president "unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office" in a written declaration. The transfer of authority to the vice president is immediate, and (as with Section 3) the vice president becomes acting president – not president – while the president remains in office, albeit divested of all authority.[6]

The "principal officers of the executive departments" are the fifteen Cabinet members enumerated in the United States Code at 5 U.S.C 101:[7][8][9]

A president declared unable to serve may issue a counter-declaration stating that he is indeed able. This marks the beginning of a four-day period during which the vice president remains acting president.[10][11] If by the end of this period the vice president and a majority of the "principal officers of the executive departments" have not issued a second declaration of the president's incapacity, then the president resumes his powers and duties.

If a second declaration of incapacity is issued within the four-day period, then the vice president remains acting president while Congress considers the matter. If within 21 days the Senate and the House determine, each by a two-thirds vote, that the president is incapacitated, then the vice president continues as acting president. If either the Senate or the House holds a vote on the question which falls short of the two-thirds requirement, or the 21 days pass without both votes having taken place, then the president resumes his powers and duties.[11][12]

Section 4's requirements for the vice president to remain acting president indefinitely – a declaration by the vice president together with a majority of the principal officers or other body, then a two-thirds vote in the House and a two-thirds vote in the Senate – contrasts with the Constitution's procedure for removal of the president from office for "high crimes and misdemeanors" – a majority of the House (Article I, Section 2, Clause 5) followed by two-thirds of the Senate (Article I, Section 3, Clause 6).[13][14]

Invocations [ edit ]

Vice presidential vacancies and succession to the presidency [ edit ]

1973: Appointment of Gerald Ford as vice president [ edit ]

On October 12, 1973, following Vice President Spiro Agnew's resignation two days earlier, President Richard Nixon nominated Representative Gerald Ford of Michigan to succeed Agnew as vice president.

The Senate voted 92–3 to confirm Ford on November 27 and, on December 6, the House of Representatives did the same by a vote of 387–35. Ford was sworn in later that day before a joint session of the United States Congress.[15]

1974: Gerald Ford succeeds Richard Nixon as president [ edit ]

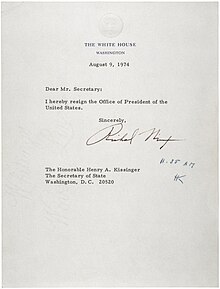

Nixon's resignation letter, August 9, 1974

When President Richard Nixon resigned on August 9, 1974, Vice President Gerald Ford succeeded to the presidency.[16] Ford is the only person ever to serve as both vice president and president without being elected to either office.[17]

1974: Appointment of Nelson Rockefeller as vice president [ edit ]

When Gerald Ford became President, the office of vice president became vacant. On August 20, 1974, after considering Melvin Laird and George H. W. Bush, Ford nominated former New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller to be the new vice president.

On December 10, Rockefeller was confirmed 90–7 by the Senate. On December 19, he was confirmed 287–128 by the House and was sworn in to office later that day in the Senate chamber.[15]

Acting Presidents [ edit ]

1985: George H. W. Bush [ edit ]

On July 12, 1985, President Ronald Reagan underwent a colonoscopy, during which a precancerous lesion was discovered. He elected to have it removed immediately[18] and consulted with White House counsel Fred Fielding about whether to invoke Section 3, and in particular about whether doing so would set an undesirable precedent. Fielding and White House Chief of Staff Donald Regan recommended that Reagan transfer power, and two letters were drafted: one specifically invoking Section 3, the other mentioning only that Reagan was mindful of its provisions. On July 13, Reagan signed the second letter,[19] and Vice President George H. W. Bush was Acting President from 11:28 a.m. until 7:22 p.m., when Reagan transmitted a followup letter declaring himself able to resume his duties.

2002: Dick Cheney [ edit ]

On June 29, 2002, President George W. Bush explicitly invoked Section 3 in temporarily transferring his powers to Vice President Dick Cheney before undergoing a colonoscopy, which began at 7:09 a.m. Bush awoke about forty minutes later but did not resume his presidential powers until 9:24 a.m.; his physician, Richard Tubb, recommended he wait to ensure the sedative had no aftereffects.[19]

2007: Dick Cheney [ edit ]

On July 21, 2007, Bush again invoked Section 3 before another colonoscopy. Cheney was acting president from 7:16 a.m. to 9:21 a.m.[19]

Considered invocations [ edit ]

There have been instances when a presidential administration has prepared for the possible invocation of Section 3 or 4 of the Twenty-fifth Amendment. None of these instances resulted in the Twenty-fifth Amendment's being invoked or otherwise having presidential authority transferred.

Section 3 [ edit ]

On December 22, 1978, President Jimmy Carter considered invoking Section 3 in advance of hemorrhoid surgery.[20] Since then, Presidents Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama also considered invoking Section 3 at various times without doing so.[21]

Section 4 [ edit ]

1981: Reagan assassination attempt [ edit ]

Following the attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan on March 30, 1981, Vice President George H. W. Bush did not assume the presidential powers and duties as Acting President. Reagan had been rushed into surgery with no opportunity to invoke Section 3; Bush did not invoke Section 4 because he was on a plane at the time of the shooting, and Reagan was out of surgery by the time Bush landed in Washington.[22] In 1995, Birch Bayh, the primary sponsor of the amendment in the Senate, wrote that Section 4 should have been invoked.[23]

1987: Reagan's alleged incapacity [ edit ]

Upon becoming the White House Chief of Staff in 1987, Howard Baker was advised by staff to prepare for a possible invocation of Section 4[24] due to Reagan's perceived laziness and ineptitude.[25][26] According to Reagan biographer Edmund Morris, Baker's staff intended to use their first meeting with Reagan to evaluate whether he was "losing his mental grip," but Reagan "came in stimulated by the press of all these new people and performed splendidly".[25][26][27] Reagan was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease in 1994, five years after leaving office.[28]

2017: Donald Trump fires FBI director James Comey [ edit ]

After President Donald Trump fired FBI Director James Comey in May 2017, Acting FBI Director Andrew McCabe held high-level discussions within the Justice Department about approaching Vice President Michael Pence and the Cabinet about a possible invocation of Section 4. It is unclear whether any Cabinet members were in fact approached.[29]

Historical background [ edit ]

The ambiguities in Article II, Section 1, Clause 6 of the Constitution regarding death, removal, or disability of the president created difficulties several times:

- In 1841, William Henry Harrison became the first US president to die in office. It had previously been suggested that the vice president would become Acting President upon the death of the president,[30] but Vice President John Tyler asserted that he had succeeded to the presidency, instead of merely assuming its powers and duties; he also declined to acknowledge documents referring to him as acting president. Although Tyler felt his vice presidential oath obviated any need for the presidential oath, he was persuaded that being formally sworn in would resolve any doubts; after taking the oath he moved into the White House and assumed full presidential powers. Though Tyler was sometimes derided as "His Accidency",[31] both houses of Congress adopted a resolution confirming that he was president. The "Tyler precedent" of succession was thus established.[32]

- Following Woodrow Wilson's stroke in 1919, no one officially assumed his powers and duties, in part because his condition was kept secret by his wife, Edith Wilson, and White House physician Cary T. Grayson.[33] By the time Wilson's condition became public knowledge, only a few months remained in his term and Congressional leaders were disinclined to press the issue.

- Prior to 1967, the office of vice president had become vacant sixteen times due to the death or resignation of the vice president or his succession to the presidency.[1] The vacancy created when Andrew Johnson succeeded to the presidency upon Abraham Lincoln's assassination was one of several that encompassed nearly the entire four-year term. In 1868, Johnson was impeached by the House of Representatives and came one vote short of being removed from office by the Senate. Had Johnson been removed, President pro tempore Benjamin Wade would have become acting president in accordance with the Presidential Succession Act of 1792.[34]

- After several periods of incapacity due to severe health problems, President Dwight D. Eisenhower attempted to clarify procedures through a signed agreement with Vice President Richard Nixon, drafted by Attorney General Herbert Brownell Jr. However, this agreement did not have legal authority.[35] Eisenhower suffered a heart attack in September 1955 and intestinal problems requiring emergency surgery in July 1956. Each time, until Eisenhower was able to resume his duties, Nixon presided over Cabinet meetings and, along with Eisenhower aides, kept the executive branch functioning and assured the public that the situation was under control. However, Nixon never made any effort to formally assume the status of Acting President or President.

Proposal, enactment, and ratification [ edit ]

Keating–Kefauver proposal [ edit ]

In 1963, Senator Kenneth Keating of New York proposed a Constitutional amendment which would have enabled Congress to enact legislation providing for how to determine when a President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of the presidency, rather than, as the Twenty-fifth Amendment does, having the Constitution so provide.[36]: 345 This proposal was based upon a recommendation of the American Bar Association in 1960.[36]: 27

The text of the proposal read:[36]: 350

In case of the removal of the President from office or of his death or resignation, the said office shall devolve on the Vice President. In case of the inability of the President to discharge the powers and duties of the said office, the said powers and duties shall devolve on the Vice President, until the inability be removed. The Congress may by law provide for the case of removal, death, resignation or inability, both of the President and Vice President, declaring what officer shall then be President, or, in case of inability, act as President, and such officer shall be or act as President accordingly, until a President shall be elected or, in case of inability, until the inability shall be earlier removed. The commencement and termination of any inability shall be determined by such method as Congress shall by law provide.

Senators raised concerns that the Congress could either abuse such authority[36]: 30 or neglect to enact any such legislation after the adoption of this proposal.[36]: 34–35 Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver, the Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee's Subcommittee on Constitutional Amendments, a long-time advocate for addressing the disability question, spearheaded the effort until he died in August 1963.[36]: 28 Senator Keating was defeated in the 1964 election, but Senator Roman Hruska of Nebraska took up Keating's cause as a new member of the Subcommittee on Constitutional Amendments.[35]

Kennedy assassination [ edit ]

By the 1960s, medical advances had made increasingly plausible the scenario of an injured or ill president living a long time while incapacitated. The assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963 demonstrated to policymakers of the need for a clear procedure for determining presidential disability, especially in the context of the Cold War.[37] The new president, Lyndon B. Johnson, had once suffered a heart attack[38] and – with the office of vice president to remain vacant until the next term began on January 20, 1965 – the next two people in the line of succession were the 71-year-old Speaker of the House John McCormack[37][39] and the 86-year-old Senate President pro tempore Carl Hayden.[37][39] Senator Birch Bayh succeeded Kefauver as Chairman of the Subcommittee on Constitutional Amendments and set about advocating for a detailed amendment dealing with presidential disability.[37]

Bayh–Celler proposal [ edit ]

On January 6, 1965, Senator Birch Bayh proposed S.J. Res. 1 in the Senate and Representative Emanuel Celler (Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee) proposed H.J. Res. 1 in the House of Representatives. Their proposal specified the process by which a President could be declared "unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office", thereby making the vice president an Acting President, and how the President could regain the powers of his office. Also, their proposal provided a way to fill a vacancy in the office of vice president before the next presidential election. This was as opposed to the Keating–Kefauver proposal, which neither provided for filling a vacancy in the office of vice president prior to the next presidential election nor provided a process for determining presidential disability. In 1964, the American Bar Association endorsed the type of proposal which Bayh and Celler advocated.[36]: 348–350 On January 28, 1965, President Johnson endorsed S.J. Res. 1 in a statement to Congress.[35] Their proposal received bipartisan support.[40]

On February 19, the Senate passed the amendment, but the House passed a different version of the amendment on April 13. On April 22, it was returned to the Senate with revisions.[35] There were four areas of disagreement between the House and Senate versions:

- the Senate official who was to receive any written declaration under the amendment

- the period of time during which the vice president and principal officers of the executive departments must decide whether they disagree with the President's declaration that he is fit to resume his duties

- the time before Congress meets to resolve the issue

- the time limit for Congress to reach a decision.[35]

On July 6, after a conference committee ironed out differences between the versions,[41] the final version of the amendment was passed by both Houses of the Congress and presented to the states for ratification.[36]: 354–358

Ratification [ edit ]

Nebraska was the first state to ratify, on July 12, 1965, and ratification became complete when Nevada became the 38th state to ratify, on February 10, 1967.[a] On February 23, 1967, at a White House ceremony certifying the ratification, President Johnson said:

It was 180 years ago, in the closing days of the Constitutional Convention, that the Founding Fathers debated the question of Presidential disability. John Dickinson of Delaware asked this question: "What is the extent of the term 'disability' and who is to be the judge of it?" No one replied.

It is hard to believe that until last week our Constitution provided no clear answer. Now, at last, the 25th amendment clarifies the crucial clause that provides for succession to the Presidency and for filling a Vice Presidential vacancy.[44]

See also [ edit ]

Notes [ edit ]

- ^

The states ratified as follows:[42]

- Nebraska (July 12, 1965)

- Wisconsin (July 13, 1965)

- Oklahoma (July 16, 1965)

- Massachusetts (August 9, 1965)

- Pennsylvania (August 18, 1965)

- Kentucky (September 15, 1965)

- Arizona (September 22, 1965)

- Michigan (October 5, 1965)

- Indiana (October 20, 1965)

- California (October 21, 1965)

- Arkansas (November 4, 1965)

- New Jersey (November 29, 1965)

- Delaware (December 7, 1965)

- Utah (January 17, 1966)

- West Virginia (January 20, 1966)

- Maine (January 24, 1966)

- Rhode Island (January 28, 1966)

- Colorado (February 3, 1966)

- New Mexico (February 3, 1966)

- Kansas (February 8, 1966)

- Vermont (February 10, 1966)

- Alaska (February 18, 1966)

- Idaho (March 2, 1966)

- Hawaii (March 3, 1966)

- Virginia (March 8, 1966)

- Mississippi (March 10, 1966)

- New York (March 14, 1966)

- Maryland (March 23, 1966)

- Missouri (March 30, 1966)

- New Hampshire (June 13, 1966)

- Louisiana (July 5, 1966)

- Tennessee (January 12, 1967)

- Wyoming (January 25, 1967)

- Washington (January 26, 1967)

- Iowa (January 26, 1967)

- Oregon (February 2, 1967)

- Minnesota (February 10, 1967)

- Nevada (February 10, 1967, at which point ratification was complete).[43]

- Connecticut (February 14, 1967)

- Montana (February 15, 1967)

- South Dakota (March 6, 1967)

- Ohio (March 7, 1967)

- Alabama (March 14, 1967)

- North Carolina (March 22, 1967)

- Illinois (March 22, 1967)

- Texas (April 25, 1967)

- Florida (May 25, 1967)

As of 2018, the following states have not ratified:

- Georgia

- North Dakota

- South Carolina

References [ edit ]

- ^ a b Kalt, Brian C.; Pozen, David. "The Twenty-fifth Amendment". The Interactive Constitution. Philadelphia, PA: The National Constitution Center . Retrieved July 20, 2018 .

- ^ Mount, Steve. "Ratification of Constitutional Amendments". ussconstitution.net . Retrieved July 20, 2018 .

- ^ Feerick, John. "Essays on Article II: Presidential Succession". The Heritage Guide to the Constitution. The Heritage Foundation . Retrieved June 12, 2018 .

- ^ Feerick, John D. (2014). The Twenty-Fifth Amendment: Its Complete History and Applications. Fordham University Press. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-0-8232-5201-5.

- ^ "Presidential Vacancy and Disability Twenty-Fifth Amendment" (PDF) . Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, Library of Congress. September 26, 2002 . Retrieved July 20, 2018 .

- ^ Bomboy, Scott (October 12, 2017). "Can the Cabinet "remove" a President using the 25th amendment?". The Constitution Center . Retrieved September 9, 2018 .

- ^ https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/olc/opinions/1985/06/31/op-olc-v009-p0065_0.pdf

- ^ "5 U.S. Code § 101 - Executive departments | US Law | LII / Legal Information Institute". Law.cornell.edu . Retrieved 2018-09-16 .

- ^ Prokop, Andrew (2018-01-02). "The 25th Amendment, explained: how a president can be declared unfit to serve". Vox . Retrieved 2018-08-09 .

- ^ Feerick, John D. (2014). The Twenty-Fifth Amendment: Its Complete History and Application. Fordham University Press. pp. 118–119. ISBN 978-0-8232-5201-5.

- ^ a b Yale Law School Rule of Law Clinic (2018). The Twenty-Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution: A Reader's Guide (PDF) . p. 38n137.

- ^ Kalt, Brian C. (2012). Constitutional cliffhangers: a legal guide for presidents and their enemies. New Haven, CN: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300123517. OCLC 842262440.

- ^ "The 25th Amendment: The Difficult Process to Remove a President". The New York Times. September 6, 2018.

- ^ Neale, Thomas H. (November 5, 2018). Presidential Disability Under the Twenty-Fifth Amendment: Constitutional Provisions and Perspectives for Congress (PDF) . Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service . Retrieved November 11, 2018 .

- ^ a b "Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum".

- ^ "Twenty-Fifth Amendment – U.S. Constitution". FindLaw.

- ^ Memorial Services in the Congress of the United States and Tributes in Eulogy of Gerald R. Ford, Late a President of the United States. Government Printing Office. 2007. p. 35. ISBN 978-0160797620.

- ^ Altman, Lawrence (July 18, 1985). "Report that Early Test was Urged Stirs Debate on Reagan Treatment". The New York Times . Retrieved 2017-03-23 .

- ^ a b c Historical Invocations of the 25th Amendment Archived July 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lipshutz, Robert J. (December 22, 1978). "Documents from Carter's Contemplated Use of Section 3 (1978)". Fordham Law School . Retrieved August 3, 2018 .

- ^ Second Fordham University School of Law Clinic on Presidential Succession, Fifty Years After the Twenty-Fifth Amendment: Recommendations for Improving the Presidential Succession System, 86 Fordham L. Rev. 917. Available at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol86/iss3/3, p. 927

- ^ Baker, James (speaker)."Remembering the Assassination Attempt on Ronald Reagan". Larry King Live, March 30, 2001.

- ^ Bayh, Birch (April 8, 1995). "The White House Safety Net". The New York Times.

- ^ The White House Chief of Staff has no formal role in the Twenty-fifth Amendment being invoked.

- ^ a b "WGBH American Experience – Reagan".

- ^ a b Linkins, Jason (February 10, 2017). "Happy 50th Birthday To The 25th Amendment To The Constitution". The Huffington Post . Retrieved February 18, 2017 .

- ^ Mayer, Jane (February 24, 2011). "Worrying About Reagan". The New Yorker . Retrieved January 15, 2018 .

- ^ Gordon, Michael R (November 6, 1994). "In Poignant Public Letter, Reagan Reveals That He Has Alzheimer's". The New York Times . Retrieved December 30, 2007 .

- ^ Devan Cole and Laura Jarrett (February 14, 2019). "McCabe confirms talks held at Justice Dept. about removing Trump". CNN . Retrieved February 14, 2019 .

- ^ Chitwood, Oliver. John Tyler: Champion of the Old South. American Political Biography Press, 1990, p. 206

- ^ "John Tyler became the tenth President of the United States (1841–1845) when President William Henry Harrison died in April 1841. He was the first vice president to succeed to the Presidency after the death of his predecessor". The White House. White House Historical Association . Retrieved January 22, 2018 .

- ^ "John Tyler, Tenth Vice President (1841)". Senate.gov . Retrieved 2009-04-29 .

- ^ Schlimgen, Joan (January 23, 2012). "Woodrow Wilson – Strokes and Denial". Arizona Health Sciences Library . Retrieved September 27, 2015 .

- ^ Amar, Akhil Reed; Amar, Vikram David (1995) [Stanford Law Review. 48 (1): 113–139]. "Is the Presidential Succession Law Constitutional?". Faculty Scholarship Series. Paper 991. Yale Law School Legal Scholarship Repository . Retrieved July 20, 2018 .

- ^ a b c d e "25th Constitutional Amendment". The Great Society Congress. Association of Centers for the Study of Congress . Retrieved April 6, 2016 .

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bayh, Birch (1968). One Heartbeat Away. ISBN 978-0672511608.

- ^ a b c d How JFK’s assassination led to a constitutional amendment, National Constitution Center, Accessed January 6, 2013

- ^ What is the 25th Amendment and When Has It Been Invoked? History News Network, Accessed January 6, 2013

- ^ a b Presidential Succession During the Johnson Administration Archived 2014-01-03 at the Wayback Machine LBJ Library, Accessed January 6, 2014

- ^ "Presidential Disability: An Overview" (PDF) . Congressional Research Service. July 12, 1999. p. 6 . Retrieved January 27, 2017 .

- ^ "Presidential Inability and Vacancies in the Office of the Vice President" (PDF) . The Association of Centers for the Study of Congress.

- ^ "Constitution of the United States of America: Analysis and Interpretation" (PDF) . Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, Library of Congress. August 26, 2017. pp. 3–44 . Retrieved July 20, 2018 .

- ^ Chadwick, John (February 11, 1967). "With Ratification of Amendment Two Gaps In Constitution Plugged". The Florence Times . Retrieved July 20, 2018 – via Google news.

- ^ Johnson, Lyndon B. (February 23, 1967). "Remarks at Ceremony Marking the Ratification of the Presidential Inability (25th) Amendment to the Constitution". Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley. Santa Barbara, CA: The American Presidency Project . Retrieved June 20, 2018 .

Sources [ edit ]

- Constitution of the United States of America

- Bayh, Birch (1968). One Heartbeat Away. ISBN 978-0672511608.

- Gant, Scott (1999). "Presidential Inability and the Twenty-Fifth Amendment's Unexplored Removal Provisions". Michigan State Law Review: 791.

- Kilman, Johnny & Costello, George Costello (Eds) (2000). The Constitution of the United States of America: Analysis and Interpretation' . Archived from the original on 2008-12-11. CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link)

- "Transcript of White House press briefing re G.W. Bush temporary transfer of power to VP Cheney". CNN. June 29, 2002 . Retrieved June 4, 2006 .

- CNN Story of White House statement regarding G.W. Bush temporary transfer of power to VP Cheney July 21, 2007.

- Presidential Inability and Subjective Meaning by Adam R.F. Gustafson, Yale Law & Policy Review, Vol. 27 (2009), p. 459.

- Presidential Succession and Inability: Before and After the Twenty-Fifth Amendment by John Feerick, Fordham Law Review, Vol. 79 (2011), p. 908.

- The Twenty-Fifth Amendment: Its Complete History and Applications, Third Edition by John Feerick (Fordham University Press, 2013).

- 25th Constitutional Amendment The Great Society Congress, Association of Centers for the Study of Congress (URL accessed April 6, 2016).

- Twenty-Fifth Amendment Archive Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History (URL accessed February 22, 2017).