New Zealand Shooting: Big Tech's Excuse for Letting Hate Go Viral

Photo: Getty

Photo: Getty

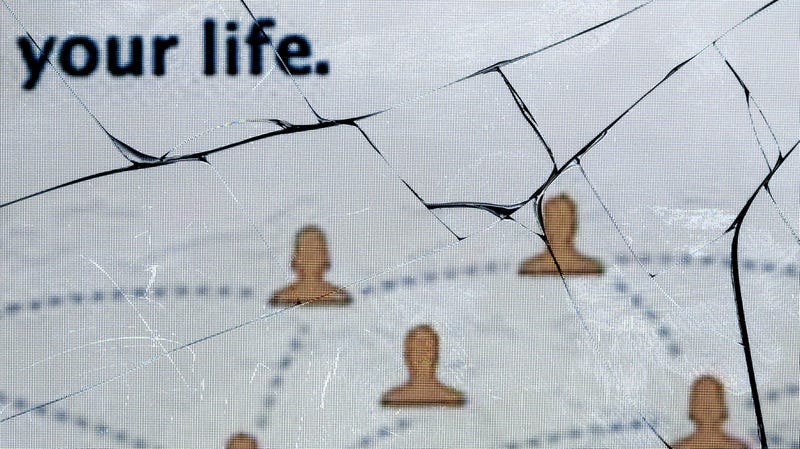

Every horrifying moment amplified by social media follows the same basic script, and Friday’s livestreamed deadly terrorist attack in New Zealand, which left at least 49 people dead and dozens injured, hits all the usual plot points of hate going viral online.

The gunman posted a livestream of his massacre on Facebook, ultimately streaming for 17 minutes. Facebook eventually removed the stream after police flagged it, but the video spread beyond its initial audience across YouTube, Reddit, Twitter, and other platforms, where it was reposted unnumbered times, spreading violence and the gunman’s hateful ideology to unknown millions of people. The companies, of course, say they’re working furiously to take down the reposted videos.

We’ve seen this time and again, so now we have to ask: Why are these big tech companies so bad at keeping the New Zealand mosque shooter’s videos off their platforms? Why do they fail at keeping the radicalizing, racist, and hateful content from saturating their sites? Why does Silicon Valley effectively fail to police their platforms? The problem goes way beyond one video of mass murder—and it goes straight to the heart of Silicon Valley’s wealth and power.

“The scale is the issue,” writer Antonio Garcia Martinez, a former Facebook advertising manager, said on Twitter on Friday when asked why.

For Silicon Valley, the scale of their platforms is what makes them multibillionaires. The unprecedented scale is an intentional creation designed for unprecedented profit. For executives, shareholders. and engineers looking for a bonus and raise, scale is everything.

Scale is also always their excuse.

By their own admission, these companies are too big to succeed at effectively moderating their platforms, particularly in a case like Friday’s explosive video of mass violence. So if they’re too big to solve this problem, perhaps it’s time to reduce their scale.

“The rapid and wide-scale dissemination of this hateful content—live-streamed on Facebook, uploaded on YouTube and amplified on Reddit—shows how easily the largest platforms can still be misused,” Senator Mark Warner said in an email to Gizmodo. “It is ever clearer that YouTube, in particular, has yet to grapple with the role it has played in facilitating radicalization and recruitment.”

If tech executives themselves are, in their own roundabout way, acknowledging that their companies are too big, maybe we should listen to them.The exact scale of these companies is difficult to know fully because of their lack of transparency. Facebook didn’t respond to a request for comment on the issue, but the company says it has 30,000 workers and artificial intelligence tasked with removing hateful content. YouTube, which apparently sees 500 minutes of video uploaded every second, said in its latest quarterly report that in the fourth quarter of 2018, the site removed 49,618 videos and 16,596 accounts for violating our policies on promotion of violence or violent extremism. They also removed 253,683 videos violating our policies on graphic violence.

Just last week, YouTube CEO Susan Wojcicki said much the same thing when journalist Kara Swisher asked the executive why neo-Nazis continue to thrive and grow on YouTube and why the website’s comments are a notoriously vile place recently reported, for one example, to be used by pedophiles to network. Her answer: The scale is the problem.

Defending her company, Wojcicki said over 500 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every single minute and that millions of bad comments are removed every quarter. “But you have to realize the volume we have is very substantial, and we’re working to give creators more tools as well for them also to be able to manage it,” she said.

Wait, exactly whose responsibility is it to manage the proliferation of groups like Nazis and pedophiles across sites like YouTube? Is it the users? On YouTube, at least, the answer is apparently yes.

When YouTube’s Twitter account posted early Friday that the company is “heartbroken” over the New Zealand killings, it provoked a reaction.

“I’m sorry, but no one cares if YouTube is heartbroken,” Jackie Luo, an engineer in the Silicon Valley tech industry, said. “Lives were lost, more will be. YouTube is complicit—not so much because of yesterday’s footage, but because of the huge role it’s played and continues to play in normalizing and spreading this kind of violent rhetoric. It’s infuriating to see a company that profits enormously from sending regular people down rabbit holes that radicalize them into having these kinds of beliefs then perform sorrow on social media when that model produces real and terrible consequences. It’s a hard ‘no’ from me.”

YouTube’s notorious radicalization problem is fuel for fire that is scale. The goal is to get more people watching, uploading, watching, uploading and consuming advertisements all the time. That’s the entire business. Radicalization just happens to be one especially effective and profitable way to accomplish the goal of growth.

“This is not because a cabal of YouTube engineers is plotting to drive the world off a cliff,” the academic Zeynep Tufekci wrote last year. “A more likely explanation has to do with the nexus of artificial intelligence and Google’s business model. (YouTube is owned by Google.) For all its lofty rhetoric, Google is an advertising broker, selling our attention to companies that will pay for it. The longer people stay on YouTube, the more money Google makes.”

Driving users to the next radical voice is part of the fundamental business—eyeballs plus hours equals ad dollars.

At a time when Washington lawmakers are talking about breaking up big tech, it’s very interesting to see a tech executive acknowledge that their platform is too big to handle the responsibility its brought on itself.

“I’m sorry, but no one cares if YouTube is heartbroken.”I’ve got my own small experience with YouTube’s radicalization business model, albeit in a much more innocuous way. I’m a runner who, until the last few years, loved quick 5K races. When I began to use YouTube more to watch running videos, the recommended and auto-play videos kept pushing me further and further along. Strangely, it assumed that a 5K runner would want to run marathons and then ultramarathons. I dutifully watched and watched before I ran a half marathon last month.

If it means watching more videos, YouTube aims to make ultramarathon-running radicals of us all because, presumably, radicalization makes for reliable and profitable consumers of content.

On Friday, over 12 hours after the event itself, videos of the gunman in Christchurch, New Zealand, killing Muslims praying at a mosque continue to spread across the internet on sites like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter as it’s used as a propaganda tool for far-right white nationalists.

“Scale is the chief problem for both FB and YouTube,” media scholar Siva Vaidhyanathan tweeted. “They would be harmless at <50 million [users].”

The reaction from New Zealand, where the attack occurred, is less forgiving.

“The failure to deal with this swiftly and decisively represents an utter abdication of responsibility by social media companies,” Tom Watson, the deputy leader of the UK’s Labour Party said. “This has happened too many times. Failing to take these videos down immediately and prevent others being uploaded is a failure of decency.”

The argument that scale is the problem and can never be completely solved comes implicitly packaged with the idea that the way things are is the way things have to be. The excuse aligns nicely with the fact that rapid speed, growth, and scale happens to make these already wildly profitable companies even more money.

‘I’m sorry that the status quo, which happens to make us wildly rich, can be so god awful,’ they seem to say. ‘But what can we possibly do?’

Scale is a Rorschach test in Silicon Valley. On one hand, it’s a goal when a tech executive is on an earnings call. On the other hand, it’s an excuse if it’s a tech spokesperson apologizing to media about the company’s failures.

If tech executives themselves are, in their own roundabout way, acknowledging that their companies are too big, maybe we should listen to them.

In Europe, regulators are looking closely at fining social media platforms that fail to remove extremist content within an hour. “One hour is the decisive time window in which the greatest damage takes place,” Jean-Claude Juncker said in last year’s State of the Union address to the European Parliament.

“We need strong and targeted tools to win this online battle,” Justice Commissioner Vera Jourova said.

The problem is attracting attention in the United States as well.

“We need strong and targeted tools to win this online battle.”Increasingly, American politicians want to do something about the scale and power of tech companies. Recently, Democratic presidential candidate Senator Elizabeth Warren proposed breaking up the big tech firms. Breaking up America’s big tech firms would push “everyone in the marketplace to offer better products and services.”

Silicon Valley companies “have a content-moderation problem that is fundamentally beyond the scale that they know how to deal with,” Becca Lewis, a researcher at Stanford University and the think tank Data & Society, told the Washington Post. “The financial incentives are in play to keep content first and monetization first. Any dealing with the negative consequences coming from that is reactive.”

Right now, the incentives line up so Silicon Valley will continue to be bad at policing the platforms they created. Incentives can be changed. In the language that Silicon Valley can understand, there are innovative ways to disrupt the social media industry’s downward spiral. One is called regulation.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misidentified Tom Watson as the deputy leader of New Zealand’s Labour Party. He is deputy leader of the UK’s Labour Party. We regret the error.