Adrenochrome - Wikipedia

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

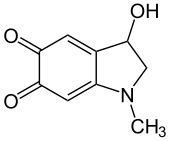

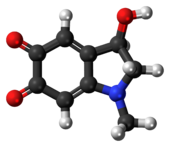

| IUPAC name

3-Hydroxy-1-methyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-indole-5,6-dione | |

| Other names

Adraxone; Pink adrenaline | |

| Identifiers | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.176 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C 9H 9N O 3 | |

| Molar mass | 179.175 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 3.264 g/cm3 |

| Boiling point | 115–120 °C (239–248 °F; 388–393 K) (decomposes) |

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state(at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

N verify (what is N verify (what is  Y Y  N ?) N ?)

| |

| Infobox references | |

Adrenochrome is a chemical compound with the molecular formula C9H9NO3 produced by the oxidation of adrenaline (epinephrine). The derivative carbazochrome is a hemostatic medication. Despite a similarity in chemical names, it is unrelated to chrome or chromium.

Chemistry [ edit ]

In vivo, adrenochrome is synthesized by the oxidation of epinephrine. In vitro, silver oxide (Ag2O) is used as an oxidizing agent.[1] Its presence is detected in solution by a pink color. The color turns brown upon polymerization.

Effect on the brain [ edit ]

Several small-scale studies (involving 15 or fewer test subjects) conducted in the 1950s and 1960s reported that adrenochrome triggered psychotic reactions such as thought disorder, euphoria and derealization.[2] Researchers Abram Hoffer and Humphry Osmond claimed that adrenochrome is a neurotoxic, psychotomimetic substance and may play a role in schizophrenia and other mental illnesses.[3] In what they called the "adrenochrome hypothesis",[4] they speculated that megadoses of vitamin C and niacin could cure schizophrenia by reducing brain adrenochrome.[5][6] The treatment of schizophrenia with such potent anti-oxidants is highly contested. In 1973, the American Psychiatric Association reported methodological flaws in Hoffer's work on niacin as a schizophrenia treatment and referred to follow-up studies that did not confirm any benefits of the treatment.[7] Multiple additional studies in the United States,[8] Canada,[9] and Australia[10] similarly failed to find benefits of megavitamin therapy to treat schizophrenia. The adrenochrome theory of schizophrenia waned, despite some evidence that it may be psychotomimetic, as adrenochrome was not detectable in schizophrenics. In the early 2000s, interest was renewed by the discovery that adrenochrome may be produced normally as an intermediate in the formation of neuromelanin. This finding may be significant because adrenochrome is detoxified at least partially by glutathione-S-transferase. Some studies have found genetic defects in the gene for this enzyme.[11]

Legal status [ edit ]

Adrenochrome is unscheduled by the Controlled Substances Act in the United States. It is not an approved drug product by the Food and Drug Administration, and if produced as a dietary supplement it must comply with good manufacturing practice.[12]

In popular culture [ edit ]

- Author Hunter S. Thompson mentioned adrenochrome in his 1971 book Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. The adrenochrome scene also appears in the novel's film adaptation. In the DVD commentary, director Terry Gilliam admits that his and Thompson's portrayal is a fictional exaggeration. Gilliam insists that the drug is entirely fictional and seems unaware of the existence of a substance with the same name. Hunter S. Thompson also mentions adrenochrome in his book Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail '72. In the footnotes in chapter April, page 140 he says, "It was sometime after midnight in a ratty hotel room and my memory of the conversation is haze, due to massive ingestion of booze, fatback, and forty cc's of adrenochrome."

- Appetite For Adrenochrome is the title of the debut album by American punk band Groovie Ghoulies.

- The harvesting of an adrenal gland from a live victim to obtain adrenochrome for drug abuse is a plot feature in the first episode "Whom the Gods would Destroy", of Series 1 of the TV series Lewis (2008).[13]

- 'Adrenochrome' is a 2018 independent film directed by Trevor Simms, starring Tom Sizemore and Larry Bishop.[14]

- Adrenochrome is also featured in a variety of conspiracy theories, such as QAnon and Pizzagate.[15]

References [ edit ]

- ^ MacCarthy, Chim, Ind. Paris 55,435(1946)

- ^ Smythies J (March 2002). "The adrenochrome hypothesis of schizophrenia revisited". Neurotoxicity Research. 4 (2): 147–50. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.688.3796 . doi:10.1080/10298420290015827. PMID 12829415.

- ^ Hoffer A, Osmond H, Smithies J (January 1954). "Schizophrenia; a new approach. II. Result of a year's research". The Journal of Mental Science. 100 (418): 29–45. doi:10.1192/bjp.100.418.29. PMID 13152519.

- ^ Hoffer A (1999). "The Adrenochrome Hypothesis and Psychiatry". The Journal of Orthomolecular Medicine. 14 (1): 49–62.

- ^ Hoffer A, Osmond H (1967). The Hallucinogens. Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-4832-6169-0.

- ^ Hoffer A (1994). "Schizophrenia: An Evolutionary Defense Against Severe Stress" (PDF) . Journal of Orthomolecular Medicine. 9 (4): 205–221.

- ^ Lipton M; et al. (1973). "Task Force Report on Megavitamin and Orthomolecular Therapy in Psychiatry". American Psychiatric Association.

- ^ Wittenborn JR, Weber ES, Brown M (1973). "Niacin in the Long-Term Treatment of Schizophrenia". Archives of General Psychiatry. 28 (3): 308–15. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1973.01750330010002. PMID 4569673.

- ^ "Nicotinic Acid in the Treatment of Schizophrenia: A Summary Report". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1 (3): 5–7. 1970. doi:10.1093/schbul/1.3.5 .

- ^ Vaughan K, McConaghy N (1999). "Megavitamin and dietary treatment in schizophrenia: a randomised, controlled trial". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 33 (1): 84–8. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1614.1999.00527.x. PMID 10197889.

- ^ John Smythies (2004). Smythies, John (ed.). Disorders of Synaptic Plasticity and Schizophrenia (1st ed.). Elsevier Academic Press. pp. xv. ISBN 9780123668608.

- ^ "Compound summary for adrenochrome". National Center for Biotechnology Information, PubChem Database . Retrieved 2020-01-22 .

- ^ "Inspector Lewis Series Synopsis". Archived from the original on 2008-06-26.

- ^ Trevor Simms (August 14, 2016). "Adrenochrome movie trailer". Youtube. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ Alex Nichols (June 6, 2019). "Slender Man for Boomers". The Outline. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

External links [ edit ]

- Adrenochrome Commentary at erowid.org

- Adrenochrome deposits resulting from the use of epinephrine-containing eye drops used to treat glaucoma from the Iowa Eye Atlas (searched for diagnosis = adrenochrome)