Black Madonna - Wikipedia

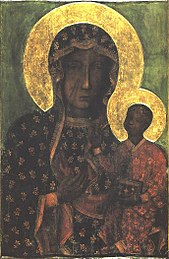

The term Black Madonna or Black Virgin tends to refer to statues or paintings in Western Christendom of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Infant Jesus, where both figures are depicted as black. The Black Madonna can be found both in Catholic and Orthodox countries.

Black Madonna of Outremeuse,

Liège, in a procession

Madonna at House of the Black Madonna, Prague

The paintings are usually icons which are Byzantine in origin or style, some made in 13th- or 14th-century Italy, others are older and from the Middle East, Caucasus or Africa, mainly Egypt and Ethiopia. Statues are often made of wood but occasionally made of stone, painted and up to 75 cm (30 in) tall. They fall into two main groups: free-standing upright figures or seated figures on a throne. There are about 400–500 Black Madonnas in Europe, depending on how they are classified. There are at least 180 Vierges Noires in Southern France alone, and there are hundreds of non-medieval copies as well. Some are in museums, but most are in churches or shrines and are venerated by believers. Some are associated with miracles and attract substantial numbers of pilgrims.

Black Madonnas come in different forms, and the speculations behind the reason for the dark hue of each individual icon or statue vary greatly and are not without controversy. Though some Madonnas were originally black or brown when they were made, others have simply turned darker due to factors like ageing or candle smoke. The Jungian scholar, Ean Begg, has conducted a study into the potential pagan origins of the cult of the black madonna and child.[1] Another speculated cause for the dark-skinned depiction is due to pre-Christian deities being re-envisioned as the Madonna and child.[2]

Studies and research Edit

Research into the Black Madonna phenomenon is limited due to a wide consensus among scholars that the dark-skinned aspect was unintentional.[citation needed ] Begg has a different view: he links the recurring refrain from the Song of Solomon, ‘I am black, and I am beautiful’ to the Queen of Sheba.[1] Recently, however, interest in this subject has gathered more momentum.

Important early studies of dark-skinned holy images in France were by Camille Flammarion (1888),[3] Marie Durand-Lefebvre (1937), Emile Saillens (1945), and Jacques Huynen (1972). The first notable study of the origin and meaning of the Black Madonnas in English appears to have been presented by Leonard Moss at a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science on December 28, 1952. Moss broke the images into three categories: (1) dark brown or black Madonnas with physiognomy and skin pigmentation matching that of the indigenous population; (2) various art forms that have turned black as a result of certain physical factors such as deterioration of lead-based pigments, accumulated smoke from the use of votive candles, and accumulation of grime over the ages, and (3) residual category with no ready explanation.[4] [5]

In the cathedral at Chartres, there were two Black Madonnas: Notre Dame de Pilar, a 1508 dark walnut copy of a 13th-century silver Madonna, standing atop a high pillar, surrounded by candles; and Notre Dame de Sous-Terre, a replica of an original destroyed during the French Revolution. Restoration work on the cathedral resulted in the painting of Notre Dame de Pilar, to reflect an earlier 19th century painted style, rendering the statue no longer a "Black Madonna".[6][7]

Some scholars chose to investigate the significance of the dark-skinned complexion to pilgrims and worshipers rather than focus on whether or not this depiction was intentional. This is an important subject because many Black Madonnas turn the shrines in which they are housed into some of the most revered pilgrimage sites, by virtue of their presence. Monique Scheer, one of these scholars, attributes the importance of the dark-skinned depiction to its connection with authenticity. The reason for this connection is the perceived age of the figures and the idea that these depictions are more accurate to historical Mary since many of the works are eastern in origin and since Mary herself likely had dark skin.[8]

List of Black Madonnas Edit

Africa Edit

Mary and child icon,

Sinai, 6th century

- Algeria, Algiers: "Our Lady of Africa"[9]

- Senegal, Popenguine: "Notre-Dame de la Délivrance"[10]

- South Africa, Soweto: "The Black Madonna"[11]

Our Lady of Guidance, Manila

Asia Edit

Japan Edit

Black Madonna at Catholic Tsuruoka Church,Japan

- Tsuruoka city, Yamagata prefecture: Tsuruoka Tenshudô Catholic Church features a black Madonna statue given by France during Meiji period[12]

The Philippines Edit

- Antipolo, Rizal: Nuestra Señora de la Paz y Buen Viaje de Antipolo (Our Lady of Peace and Good Voyage of Antipolo)[13]

- Ermita, City of Manila: Nuestra Señora de Guia (Our Lady of Guidance)

- Lapu-Lapu City: Nuestra Señora de la Regla (Our Lady of the Rule)[14]

- Naga, Camarines Sur: Nuestra Señora de Peñafrancia (Our Lady of Peñafrancia)

- Piat, Cagayan: Nuestra Señora de la Visitación de Piat (Our Lady of Piat)[15]

- Joroan, Tiwi, Albay: Mater Salutis (Mother of Our Salvation)

Europe Edit

Austria Edit

- St. Andrä im Lavanttal „Schwarze Madonna von Loreto“ Basilica Maria Loreto

Belgium Edit

- Brugge, "Our Lady of Regla"[16]

- Brussels: "De Zwerte Lieve Vrouwo", St. Catherine Church

- Halle (Flemish Brabant) : Sint-Martinusbasiliek

- Liège: La Vierge Noire d'Outremeuse,

- Lier: Onze lieve vrouw ter Gratien

- Scherpenheuvel-Zichem: Our Lady of Scherpenheuvel

- Tournai: Our Lady of Flanders in Tournai Cathedral

- Verviers: "Black Virgin of the Recollects", Notre-Dame des Récollets Church,

- Walcourt: (Notre-Dames de Walcourt)

Croatia Edit

- Marija Bistrica: Our Lady of Bistrica, Queen of Croatia

Czech Republic Edit

- Brno: Assumption of Virgin Mary Minor Basilica, St Thomas's Abbey, Brno[17]

- Prague: The Madonna of Breznice; The Black Madonna in the Church Our Lady Under the Chain[18] The Black Madonna on the House of the Black Madonna.

France Edit

Black Madonna of Toulouse

- Aix-en-Provence, (Bouches-du-Rhône): Notre-Dame des Graces, Cathédrale Saint-Sauveur d'Aix[19]

- Arconsat: (Notre-Dame des Champs)

- Aurillac, (Cantal): Notre-Dame des Neiges[20]

- Beaune: Our Lady of Beaune

- Besançon: Our Lady de Gray

- Besse-et-Saint-Anastaise,(Puy-de-Dôme): Saint-André Church, Notre-Dame de Vassivière

- Bourg-en-Bresse, (Ain): 13th century

- Chartres, (Eure-et-Loir): crypt of the Cathedral of Chartres, Notre-Dame-de-Sous-Terre[21]

- Clermont-Ferrand, (Puy-de-Dôme)[22]

- Cusset: the Black Virgin of Cusset

- Dijon, (Côte-d'Or)

- Douvres-la-Délivrande, Basilique Notre-Dame de la Délivrande, "Notre-Dame de la Délivrande"[23]

- Dunkerque, (Nord) : Chapelle des Dunes

- Guingamp, (Côtes-d'Armor): Basilica of Notre Dame de Bon Secours.

- La Chapelle-Geneste, (Haute-Loire: Notre Dame de La Chapelle Geneste[24]

- Laon,(Aisne): Notre-Dame Cathedral, statue of 1848

- Le Havre,(Seine-Maritime): statue near the Graville Abbey (Abbaye de Graville)

- Le Puy-en-Velay: In 1254 when passing through on his return from the Holy Land Saint Louis IX of France gave the cathedral an ebony image of the Blessed Virgin clothed in gold brocade (Notre-Dame du Puy). It was destroyed during the Revolution, but replaced at the Restoration with a copy that continues to be venerated.[25]

- Liesse-Notre-Dame, (Aisne): Notre-Dame de Liesse, statue destroyed in 1793, copy of 1857

- Marseille,(Bouches-du-Rhône): Notre-Dame-de-Confession,[26] Abbey of St. Victor ; Notre-Dame d'Huveaune, Saint-Giniez Church

- Mauriac, Cantal: Notre Dame des Miracles[27]

- Mende, (Lozère) : Cathedral (Basilique-cathédrale Notre-Dame-et-Saint-Privat de Mende)

- Menton, (Alpes-Maritimes): St. Michel Church

- Meymac Abbey, (Corrèze)[28]

- Molompize: Notre-Dame de Vauclair

- Mont-Saint-Michel: Notre-Dame du Mont-Tombe

- Myans, (Savoie)

- Paris, (Neuilly-sur-Seine): Notre-Dame de Bonne Délivrance, in the motherhouse of the Sisters of St. Thomas of Villanova[29]

- Quimper,(Finistère): Eglise de Guéodet, nommée encore Notre-Dame-de-la-Cité

- Riom,(Puy-de-Dôme): Notre-Dame du Marthuret[30]

- Rocamadour, (Lot): Our Lady of Rocamadour [31]

- Sainte Marie (Réunion) : Black Virgin River Rains [fr]

- Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer (Camarque) Avignon: Annual Gypsy festival[32] celebrating Sara, the patron saint of Gypsies[33]

- Soissons (Aisne): statue of the 12th century

- Tarascon, (Bouches-du-Rhône): Notre-Dame du Château[34]

- Thuret,(Puy-de-Dôme)[35]

- Toulouse: The basilica Notre-Dame de la Daurade in Toulouse, France had housed the shrine of a Black Madonna. The original icon was stolen in the fifteenth century, and its first replacement was burned by Revolutionaries in 1799 on the Place du Capitole. The icon presented today is an 1807 copy of the fifteenth century Madonna. Blackened by the hosts of candles, the second Madonna was known from the sixteenth century as Our Lady La Noire[36]

- Tournemire, Château d'Anjony, Our Lady of Anjony

- Vaison-la-Romaine, (Vaucluse): statue on a hill

- Vichy, (Allier): Saint-Blaise Church

Germany Edit

- Altötting (Bavaria): Gnadenkapelle (Chapel of the Miraculous Image)

- Beilstein (Rhineland-Palatinate): Karmeliterkirche St. Joseph

- Bielefeld (North Rhine-Westphalia)

- Düsseldorf-Benrath (North Rhine-Westphalia): Pfarrkirche St. Cäcilia

- Hirschberg an der Bergstraße (Baden-Württemberg): Wallfahrtskirche St. Johannes Baptist

- Schloss Hohenstein, Upper Franconia (Bavaria)

- Köln (Nord Rhein Westfalen): St. Maria in der Kupfergasse

- Ludwigshafen-Oggersheim (Rhineland-Palatinate): Schloss- und Wallfahrtskirche Mariä Himmelfahrt (Ludwigshafen)

- Mainau (Baden-Württemberg): Schlosskirche St. Marien

- Munich (Bavaria): Theatine Church; St. Boniface's Abbey

- Rastatt (Baden-Württemberg): Einsiedelner Kapelle

- Regensburg (Bavaria): Regensburg Cathedral

- Remagen (Rhineland-Palatinate): Kapelle Schwarze Madonna

- Spabrücken (Rhineland-Palatinate)

- Stetten ob Lontal, Niederstotzingen (Baden-Württemberg)

- Windhausen in Boppard-Herschwiesen (Rhineland-Palatinate)

- Wipperfürth (North Rhine-Westphalia): St. Johannes, Kreuzberg

- Wuppertal-Beyenburg (North Rhine-Westphalia)

Greece Edit

Hidden church of the Black Madonna, Vamos, Crete

Hungary Edit

- Cathedral Basilica of Eger: Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception

Ireland Edit

Italy Edit

TindariMadonna Bruna: restoration work in the 1990s found a medieval statue with later additions.

Nigra sum sed formosa, meaning "I am black but beautiful" (from the

Song of Songs, 1:5), is inscribed round a newer base.

- Biella (Piedmont): Black Virgin of Oropa, sanctuary of Oropa

- Canneto Valley near Settefrati (Lazio): Madonna di Canneto

- Casale Monferrato (Piedmont): Our Lady of Crea. In the hillside Sanctuary at Crea (Santuario di Crea), a cedar-wood figure, said to be one of three Black Virgins brought to Italy from the Holy Land c. 345 by St. Eusebius.

- Castelmonte, Prepotto (Friuli-Venezia Giulia)

- Gubbio, Italy: The NIGER-REGIN square, discovered carved in the cave of Sibilla Eugubina on Mount Ingino, is considered to be a word square from the “Black Queen”. Seemingly of Neo-Templar origin, its dated between 1600-1800 CE, was discovered in 2003, and destroyed by vandalism in 2012.[37][38][39]

| N I G E R |

| I N A R E |

| G A L A G |

| E R A N I |

| R E G I N |

- Loreto (Marche): Basilica della Santa Casa

- Naples (Campania): Santuario-Basilica SS Carmine Maggiore

- Pescasseroli (Abruzzo): Madonna di Monte Tranquillo

- Positano (Campania): Located in the church of Santa Maria Assunta, the story of how it got there—sailors shouting "Posa, posa!" ("Put it down, put it down!")—gave the town its name.

- San Severo (Apulia): "La Madonna del Soccorso" (The Madonna of Succor), St. Severinus Abbot and Saint Severus Bishop Faeto. Statue in gold garments, object of a major three-day festival that attracts over 350,000 people to this small town.

- Seminara (Calabria): Maria Santissima dei poveri

- Tindari (Sicily): Our Lady of Tindari

- Torre Annunziata (Campania): Madonna della Neve

- Venice (Veneto): Madonna della Salute, Santa Maria della Salute

- Viggiano (Basilicata)

Kosovo Edit

- Vitina-Letnica: Church of the Black Madonna, where Mother Teresa is believed to have heard her calling.

Lithuania Edit

- Aušros vartai: Our Lady of the Gate of Dawn

- Our Lady of Šiluva: Our Lady of the Pine Woods

Luxembourg Edit

- Esch-sur-Sûre

- Luxembourg: Luxembourg-Grund

Macedonia Edit

- Kališta, Monastery: Madonna icon in the Nativity of Our Most Holy Mother of God church

- Ohrid, Church: Madonna with the child

Malta Edit

- Ħamrun: Our Lady of Atoċja, a medieval painting brought to Malta by a merchant in the year 1630, depicting a statue found in Atocha, a parish in Madrid, Spain, and widely known as Il-Madonna tas-Samra. (This can mean 'tanned Madonna', 'brown Madonna', or 'Madonna of Samaria'.)

Poland Edit

- Częstochowa: Our Lady of Czestochowa

- In the United States, the National Shrine of Our Lady of Czestochowa, in Doylestown, Pennsylvania houses a reproduction of the Black Madonna of Częstochowa. a second shrine to Our Lady of Częstochowa is located near Eureka, Missouri.

- In Israel there are two reproductions of the Black Madonna of Częstochowa: One in St. Peter's Church in Tel Aviv, and another in the Abbey of the Dormition in Jerusalem.[40][41][42][43][44][45]

- Głogówek: Our Lady of Loretto

Portugal Edit

Romania Edit

- Ghighiu: Maica Domnului Siriaca – Manastirea Ghighiu

- Cacica: Madona Neagra – Biserica Cacica

- Bucuresti: Madona Neagra – Biserica Dichiu

Russia Edit

- Kostroma (Kostroma Oblast): Theotokos of St. Theodore also known as Our Lady of St. Theodore (Федоровская Богоматерь), in Theophany Monastery

- Our Lady of Wladimir, from the 12th century

- Black Virgin of Taganrog, Taganrog Old Cemetery

Serbia Edit

Slovenia Edit

- Koprivna, Črna na Koroškem: St. Anne's Church, Koprivna – the altar of Black Madonna

Spain Edit

- Andújar (Province of Jaén): Nuestra Señora de la Cabeza (Our Lady of Cabeza), named after the mountain, Cerro de la Cabeza or Cerro de Cabezo.

- Chipiona (Province of Cádiz): La Virgen de Regla or Nuestra Señora de Regla (Our Lady of Regla or the Virgin of Regla), considered by some as the custodian of the Rule of Saint Augustine

- Coria (Province of Cáceres): Virgen de Argeme (Our Lady of Argeme)

- El Puerto de Santa María (Province of Cádiz): Virgen de los Milagros (The Virgin of the Miracles)

- Guadalupe (Province of Cáceres): Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe, Extremadura)

- Jerez de la Frontera (Province of Cádiz): Nuestra Señora de la Merced (Our Lady Of Mercy)

- Madrid (Community of Madrid): Nuestra Señora de Atocha (Our Lady of Atocha)

- Lluc, Majorca (Balearic Islands): Mare de Déu de Lluc (Our Lady of Lluc), Lluc Monastery

- Monistrol de Montserrat (Catalonia): Mare de Déu de Montserrat (Virgin of Montserrat) or "La Moreneta" in the Benedictine abbey of Santa Maria de Montserrat

- Ponferrada (Province of León): Virgen de la Encina (Our Lady of the Holm Oak)

- Salamanca (Province of Salamanca): Virgen de la Peña de Francia (The Virgin of France's Rock, named after the local mountain called Peña de Francia)

- Santiago de Compostela (Galicia):

- Tenerife (Canary Islands): Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria (Virgin of Candelaria), or "La Morenita"

- Toledo (Province of Toledo): Virgen Morena (Dark Virgin), statue of La Esclavitud de Nuestra Señora del Sagrario in the Cathedral of Toledo (Catedral Primada de Santa María) (The Enslavement of Our Lady of the Tabernacle)

- Torreciudad (Huesca): Our Lady of Torreciudad

Sweden Edit

- Lunds Domkyrka Lund Cathedral Attached to a marble pillar in the crypt: Black madonna with child

- Skee Kyrka Bohuslän former Norwegian and Danish province. Black madonna with beheaded child [1]

Switzerland Edit

- Einsiedeln (Canton of Schwyz): Our Lady of the Hermits

- Sonogno, Valle Verzasca (Canton of Ticino): Santa Maria Loretana

- Uetikon upon Lake (Canton of Zürich): Catholic Church Saint Francis of Assisi

- Metzerlen-Mariastein (Canton of Solothurn): Mariastein Abbey

- Ascona (Canton of Ticino): Black Chapel

- Lugano (Canton of Ticino): Chiesa di Santa Maria di Loreto

Turkey Edit

Three icons portraying the Theotokos with black skin survived in Turkey to the present day, one of which is housed in the church of Halki theological seminary.

Ukraine Edit

- Tsarytsya Karpat (Hoshiv Monastery): The Queen of the Carpathian Land

United Kingdom Edit

- St. Mary Willesden (Our Lady of Willesden): The original Shrine of Our Lady of Willesden.

- Our Lady of Częstochowa (Our Lady of Częstochowa church Nottingham)

The Americas Edit

Brazil Edit

- Aparecida, São Paulo: Our Lady of Aparecida or Our Lady Appeared (Nossa Senhora Aparecida or Nossa Senhora da Conceição Aparecida) in the Basilica of the National Shrine of Our Lady of Aparecida

Chile Edit

- Andacollo, Elqui Province: La Virgen Morena (Spanish for The Brunette Virgin)

Costa Rica Edit

- Cartago, Cartago Province: Basílica de Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles (Our Lady of the Angels Basilica)

Cuba Edit

- Regla, Havana Province: Nuestra Señora de Regla (Spanish for Our Lady of Regla)

Trinidad and Tobago Edit

United States Edit

See also Edit

References Edit

- ^ a b Begg, Ean (2017). The Cult of the Black Virgin. Chiron Publications. ISBN 978-1630514419.

- ^ Moss, Leonard W.; Cappannari, Stephen C. (1953). "The Black Madonna: An Example of Culture Borrowing". The Scientific Monthly. 76 (6): 319–324. Bibcode:1953SciMo..76..319M. ISSN 0096-3771. JSTOR 20482.

- ^ L'Atmosphère : Météorologie populaire (1888), édition avec gravures fr.

- ^ "Black Madonnas: Origin, History, Controversy". udayton.edu. The Jungian scholar, San Begg published a study of Black Virgins and their possible pagan origins.

- ^ Begg, Ean (2006). The Cult of the Black Virgin. Chiron Publications. ISBN 9781888602395.

- ^ Filler, Martin "A Scandalous Makeover at Chartres", The New York Review of Books, December 14, 2014

- ^ Ramm, Benjamin. "A Controversial Restoration That Wipes Away the Past", The New York Times, September 1, 2017

- ^ Scheer, Monique (2002). "From Majesty to Mystery: Change in the Meanings of Black Madonnas from the Sixteenth to Nineteenth Centuries". The American Historical Review. 107 (5): 1412–1440. doi:10.1086/532852. JSTOR 10.1086/532852.

- ^ "Algiers". interfaithmary.net.

- ^ "Senegal". interfaithmary.net.

- ^ "Soweto". interfaithmary.net.

- ^ "Experiencetsuruoka.com". Archived from the original on 2017-09-03 . Retrieved 2017-09-03 .

- ^ Baybay, Felicito S., "Patron Ng Kapayapaan At Mga Manlalakbay" Archived 2014-08-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ KD. "Our Lady Of The Rule National Shrine – Quirks of Life". quirksoflife.com.

- ^ Darang, Josephine. "Special Mass for Our Lady of Piat held July 9 at Sto. Domingo Church", Philippine Daily Enquirer, June 26, 2011

- ^ "Your Question". udayton.edu. Archived from the original on 2015-02-19 . Retrieved 2014-08-06 .

- ^ "Brno – The Black Madonna". brno.cz. Archived from the original on 2013-09-28 . Retrieved 2013-08-16 .

- ^ "Church of Our Lady Below the Chain in Prague", Prague.cz Archived November 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Channell, J., "Notre-Dame des Graces", Aix-en-Provence

- ^ "Black Virgin of Aurillac". amigo.net. Archived from the original on 15 May 2008.

- ^ The New York Times

- ^ "Notre Dame de Clermont". 2007-12-19. Archived from the original on 2007-12-19 . Retrieved 2009-07-25 .

- ^ "Douvres". interfaithmary.net.

- ^ "Notre Dame de La Chapelle Geneste". amigo.net. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008.

- ^ "Notre Dame du Puy, Cathedrale...: Photo by Photographer Dennis Aubrey". photo.net. 2007-11-09. Archived from the original on 2009-02-07 . Retrieved 2009-07-25 .

- ^ "Black Virgin of Marseilles". amigo.net. Archived from the original on 15 May 2008.

- ^ "Black Virgin of Mauriac". amigo.net. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008.

- ^ "Meymac". interfaithmary.net.

- ^ Mariancalendar.org

- ^ "Black Virgin of Riom". amigo.net. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008.

- ^ "The Sanctuaries". visit-dordogne-valley.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2014-07-05 . Retrieved 2014-08-06 .

- ^ Garth Cartwright (2011-03-26). "Partying with the Gypsies in the Camargue". the Guardian.

- ^ "Gypsy's Pilgrimage – Les Saintes Maries de la Mer – Camargue – France". avignon-et-provence.com.

- ^ "Notre Dame du Château". amigo.net. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008.

- ^ "Vierge des Croisades". 2007-12-19. Archived from the original on 2007-12-19 . Retrieved 2009-07-25 .

- ^ Vanished Kingdoms: The History of Half-Forgotten Europe, Norman Davies

- ^ Maria Farneti and Bruno Bartoletti, “Gubbio: The Italian Rennes-le-Chateau”, 'Hera', issue 43, September 2005

- ^ Gubbio e il mysterious del “NIGER REGIN”

- ^ “IL MONTE TEMPIO E LA PIRAMIDE DI GUBBIO” by Mario Farneti & Bruno Bartoletti

- ^ https://literia.pl/ksiazka-czarna-madonna-978-83-7976-710-6

- ^ https://www.dreamstime.com/stock-photo-tel-aviv-icon-black-madonna-st-peters-church-old-jaffa-unknown-artist-end-cent-image56128953

- ^ https://www.123rf.com/photo_41648797_tel-aviv-israel-march-2-2015-the-icon-of-black-madonna-from-st-peters-church-in-old-jaffa-by-unknown.html

- ^ https://stock.adobe.com/pl/images/tel-aviv-icon-of-black-madonna-from-st-peters-church/86100805

- ^ https://pixers.uk/posters/jerusalem-mosaic-of-madonna-in-dormition-abbey-81580365

- ^ https://pixers.uk/stickers/jerusalem-mosaic-of-madonna-in-dormition-abbey-81580365

- ^ Dhalai, Richard, "La Divina Pastora", Trinidad and Tobago Newsday, March 19, 2007

- ^ Nationaltrust.tt

Sources Edit

- Channell, J., "Black Virgin Sites in France"

- Rozett, Ella. "Index of Black Madonnas Worldwide", InterfaithMary.net

External links Edit

- List of Black Madonnas

- The Black Virgin – Karen Ralls

- Montserrat

- Pilgrimage

- Black Madonna gallery by Canon Jim Irvine, New Brunswick, Canada

- The Black Madonna "The work of God"

- Nuestra Señora de Atocha

- Black Madonna Pilgrimage to Central France

- Black Madonna photo collection on Flickr

- Black Madonnas and other Mysteries of Mary – Ella Rozett

- Sciorra, Joseph. "The Black Madonna of Thirteenth Street", Voices: The Journal of New York Folklore, Vol. 30, Spring-Summer 2004

- Black Madonna in modern art - see Black Madonna by BystreetSky Artist https://web.archive.org/web/20180802193137/https://www.bystreetsky.com/bystreetsky-art?lightbox=dataItem-j74w6ola