- Moe Factz with Adam Curry for September 11th 2024, Episode number 100 - "Hard R"

- ----

- This is it! The pinnacle! We have reached the mountaintop. Welcome to 100, the final episode!

- I'm Adam Curry coming to you from the heart of The Texas Hill Country and it's time once again to spin the wheel of Topics from here to Northern Virginia, please say hello to my friend on the other end: Mr. Moe Factz

- Moe and Adam finish their series of 100 episodes by really "going there"!

- Chapter Architect: Dreb Scott

- Associate Executive Producers

- Boost us with Value 4 Value on:

- Shownotes

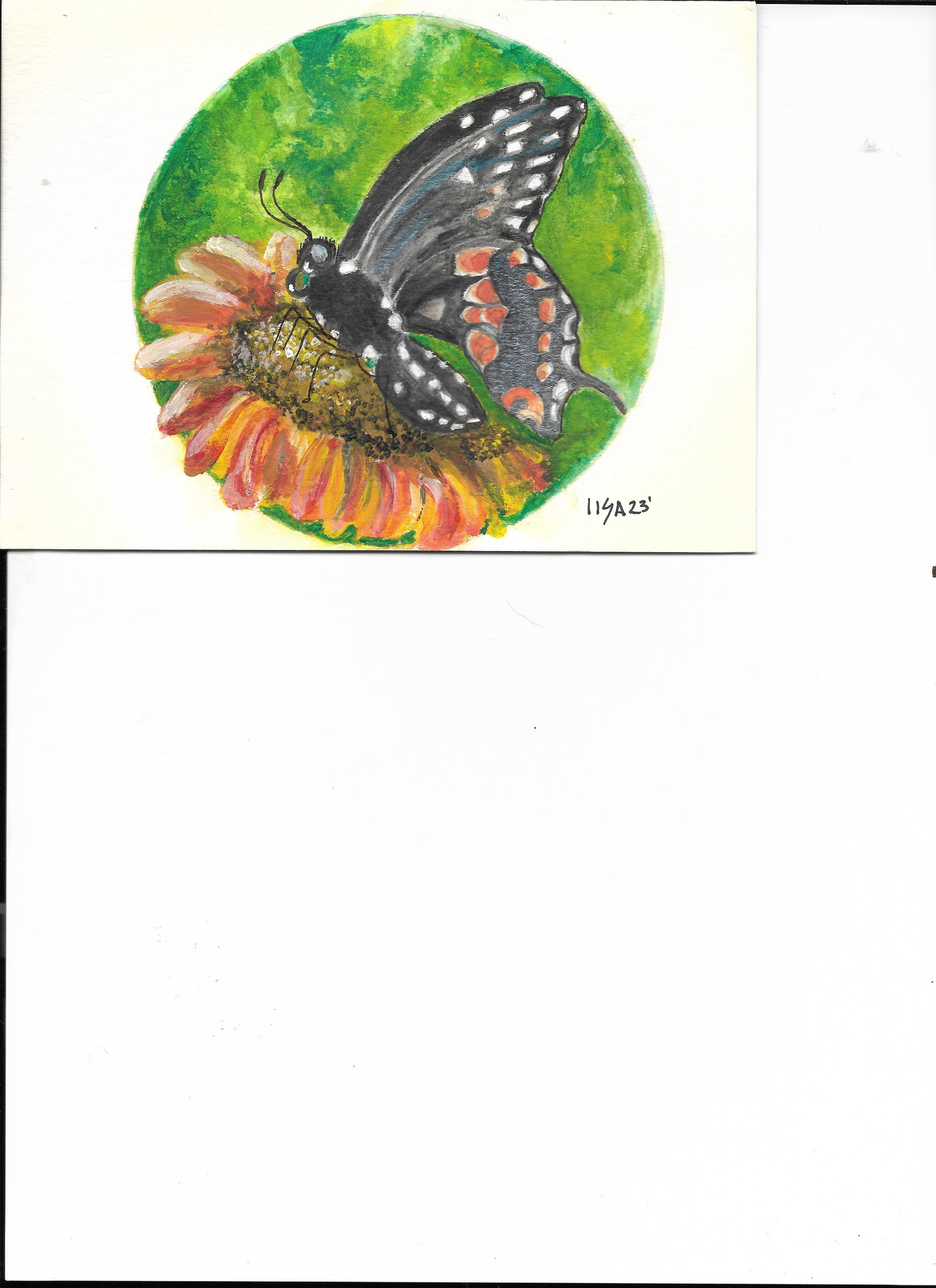

- Renegade 6 + Sparkles of Chaos Painting

- FACT SHEET: President Obama Announces New Actions to Promote Rehabilitation and Reintegration for the Formerly- Incarcerated | whitehouse.gov

- This Administration has consistently taken steps to make our criminal justice system fairer and more effective and to address the vicious cycle of poverty, criminality, and incarceration that traps too many Americans and weakens too many communities. Today, in Newark, New Jersey, President Obama will continue to promote these goals by highlighting the reentry process of formerly-incarcerated individuals and announce new actions aimed at helping Americans who've paid their debt to society rehabilitate and reintegrate back into their communities.

- Each year, more than 600,000 individuals are released from state and federal prisons. Advancing policies and programs that enable these men and women to put their lives back on track and earn their second chance promotes not only justice and fairness, but also public safety. That is why this Administration has taken a series of concrete actions to reduce the challenges and barriers that the formerly incarcerated confront, including through the work of the Federal Interagency Reentry Council, a cabinet-level working group to support the federal government's efforts to promote public safety and economic opportunity through purposeful cross-agency coordination and collaboration.

- The President has also called on Congress to pass meaningful criminal justice reform, including reforms that reduce recidivism for those who have been in prison and are reentering society. The Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2015, which recently received a strong bipartisan vote in the Senate Judiciary Committee, would be an important step forward in this effort, by providing new incentives and opportunities for those incarcerated to participate in the type of evidence-based treatment and training and other programs proven to reduce recidivism, promote successful reentry, and help eliminate barriers to economic opportunity following release. By reducing overlong sentences for nonviolent drug offenses, the bill would also free up additional resources for investments in other public safety initiatives, including reentry services, programs for mental illness and addiction, and state and local law enforcement.

- Today, the President is pleased to announce the following measures to help promote rehabilitation and reintegration:

- Adult Reentry Education Grants. The Department of Education will award up to $8 million (over 3 years) to 9 communities for the purpose of supporting educational attainment and reentry success for individuals who have been incarcerated. This grant program seeks to build evidence on effective reentry education programs and demonstrate that high-quality, appropriately designed, integrated, and well-implemented educational and related services in institutional and community settings are critical in supporting educational attainment and reentry success. Arrests Guidance for Public and other HUD-Assisted Housing. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) will release guidance today to Public Housing Authorities and owners of HUD-assisted housing regarding the use of arrests in determining who can live in HUD-assisted properties. This Guidance will also clarify the Department's position on ''one strike'' policies and will include best practices from Public Housing Authorities.Banning the Box in Federal Employment. The President has called on Congress to follow a growing number of states, cities, and private companies that have decided to ''ban the box'' on job applications. We are encouraged that Congress is considering bipartisan legislation that would ''ban the box'' for federal hiring and hiring by federal contractors. In the meantime, the President is directing the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) to take action where it can by modifying its rules to delay inquiries into criminal history until later in the hiring process. While most agencies already have taken this step, this action will better ensure that applicants from all segments of society, including those with prior criminal histories, receive a fair opportunity to compete for Federal employment. TechHire: Expanding tech training and jobs for individuals with criminal records. As a part of President Obama's TechHire initiative, over 30 communities are taking action '' working with each other and national employers '' to expand access to tech jobs for more Americans with fast track training like coding boot camps and new recruitment and placement strategies. Today we are announcing the following new commitments:Memphis, TN and New Orleans, LA are expanding TechHire programs to support people with criminal records. Newark, NJ, working with the New Jersey Institute of Technology and employers like Audible, Panasonic, and Prudential, will offer training through the Art of Code program in software development with a focus on training and placement for formerly incarcerated people.New Haven, CT, Justice Education Center, New Haven Works, and others will launch a pilot program to train and place individuals with criminal records, and will start a program to train incarcerated people in tech programming skills. Washington, DC partners will train and place 200 formerly incarcerated people in tech jobs. They will engage IT companies to develop and/or review modifications to hiring processes that can be made for individuals with a criminal record.Establishing a National Clean Slate Clearinghouse. In the coming weeks, the Department of Labor and Department of Justice will partner to establish a National Clean Slate Clearinghouse to provide technical assistance to local legal aid programs, public defender offices, and reentry service providers to build capacity for legal services needed to help with record-cleaning, expungement, and related civil legal services. Permanent Supportive Housing for the Reentry Population through Pay for Success. The Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Bureau of Justice Assistance at the Department of Justice have launched an $8.7 million demonstration grant to address homelessness and reduce recidivism among the justice-involved population. The Pay for Success (PFS) Permanent Supportive Housing Demonstration will test cost-effective ways to help persons cycling between the criminal justice and homeless service systems, while making new Permanent Supportive Housing available for the reentry population. PFS is an innovative form of performance contracting for the social sector through which government only pays if results are achieved. This grant will support the design and launch of PFS programs to reduce both homelessness and jail days, saving funds to criminal justice and safety net systems.Juvenile Reentry Assistance Program Awards to Support Public Housing Residents. With funding provided by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention at the Department of Justice, the Department of Housing and Urban Development will provide $1.75 million to aid eligible public housing residents who are under the age of 25 to expunge or seal their records in accordance with their applicable state laws. In addition, the National Bar Association '' the nation's oldest and largest national association of predominantly African-American lawyers and judges '' has committed to supplementing this program with 4,000 hours of pro bono legal services. Having a criminal record can result in major barriers to securing a job and other productive opportunities in life, and this program will enable young people whose convictions are expungable to start over.Many of the announcements being made today stem from the President's My Brother's Keeper Task Force, which is charged with addressing persistent opportunity gaps facing boys and young men of color and ensuring all young people can reach their full potential. In May of 2014, the Task Force provided the President with a series of evidence-based recommendations focused on the six key milestones on the path to adulthood that are especially predictive of later success, and where interventions can have the greatest impact, including Reducing Violence and Providing a Second Chance. The Task Force, made up of key agencies across the Federal Government, has made considerable progress towards implementing their recommendations, many times creating partnerships across agencies and sectors. Today's announcements respond to a wide range of recommendations designed to ''eliminate unnecessary barriers to giving justice-involved youth a second chance.''

- These announcements mark a continuation of the Obama Administration's commitment to mitigating unnecessary collateral impacts of incarceration. In particular, the Administration has advanced numerous effective reintegration strategies through the work of the Federal Interagency Reentry Council, whose mission is to reduce recidivism and victimization; assist those returning from prison, jail or juvenile facilities to become productive citizens; and save taxpayer dollars by lowering the direct and collateral costs of incarceration.

- Through the Reentry Council and other federal agency initiatives, the Administration has improved rehabilitation and reintegration opportunities in meaningful ways, including recent initiatives in the following areas:

- Reducing barriers to employment.

- Last month, the Department of Justice awarded $3 million to provide technology-based career training for incarcerated adults and juveniles. These funds will be used to establish and provide career training programs during the 6-24 month period before release from a prison, jail, or juvenile facility with connections to follow-up career services after release in the community.

- The Department of Justice also announced the selection of its first-ever Second Chance Fellow, Daryl Atkinson. Recognizing that many of those directly impacted by the criminal justice system hold significant insight into reforming the justice system, this position was designed to bring in a person who is both a leader in the criminal justice field and a formerly incarcerated individual to work as a colleague to the Reentry Council and as an advisor to the Bureau of Justice Assistance Second Chance programs.

- In addition, the Department of Labor awarded a series of grants in June that are aimed at reducing employment barriers, including:

- Face Forward: The Department awarded $30.5 million in grants to provide services to youth, aged 14 to 24, who have been involved in the juvenile justice system. Face Forward gives youth a second chance to succeed in the workforce by removing the stigma of having a juvenile record through diversion and/or expungement strategies. Linking to Employment Activities Pre-Release (LEAP): The Department awarded $10 million in pilot grants for programs that place One Stop Career Center/American Job Centers services directly in local jails. These specialized services will prepare individuals for employment while they are incarcerated to increase their opportunities for successful reentry.Training to Work: The Department awarded $27.5 million in Training to Work grants to help strengthen communities where formerly incarcerated individuals return. Training to Work provides workforce-related reentry opportunities for returning citizens, aged 18 and older, who are participating in state and/or local work-release programs. The program focuses on training opportunities that lead to industry-recognized credentials and job opportunities along career pathways. Increasing access to education and enrichment.

- High-quality correctional education '-- including postsecondary correctional education '-- has been shown to measurably reduce re-incarceration rates. In July, the Departments of Education and Justice announced the Second Chance Pell Pilot Program to allow incarcerated Americans to receive Pell Grants to pursue postsecondary education and trainings that can help them turn their lives around and ultimately, get jobs, and support their families. Since this pilot was announced, over 200 postsecondary institutions across the nation have applied for consideration.

- In June, the Small Business Administration published a final rule for the Microloan Program that provides more flexibility to SBA non-profit intermediaries and expands the pool of microloan recipients. The change will make small businesses that have an owner who is currently on probation or parole eligible for microloan programs, aiding individuals who face significant barriers to traditional employment to reenter the workforce.

- Expanding opportunities for justice-involved youth to serve their communities.

- In October, the Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS) and the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention at the Department of Justice announced a new round of Youth Opportunity AmeriCorps grants aimed at enrolling at-risk and formerly incarcerated youth in national service projects. These grants, which include $1.2 million in AmeriCorps funding, will enable 211 AmeriCorps members to serve through organizations in Washington, D.C. and four states: Maine, Maryland, New York, and Texas.

- In addition, the Department of Labor partnered with the Department of Defense's National Guard Youth ChalleNGe program and awarded three $4 million grants in April of this year to provide court-involved youth with work experiences, mentors, and vocational skills training that prepares them for successful entry into the workforce.

- Increasing access to health care and public services.

- In October, the Department of Justice announced $6 million in awards under the Second Chance Act to support reentry programming for adults with co-occurring substance abuse and mental disorders. This funding is aimed at increasing the screening and assessment that takes place during incarceration as well as improving the provision of treatment options.

- In September, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) at HHS announced the winners of its reintegration toolkit challenge to develop software applications aimed at transforming existing resources into user-friendly tools with the potential to promote successful reentry and reduce recidivism. And in October, HHS issued a ''Guide for Incarcerated Parents with Children in the Child Welfare System'' in order to help incarcerated parents who have children in the child welfare system, including in out-of-home-care, better understand how the child welfare system works so that they can stay in touch.'' The information can be found at: http://youth.gov/youth-topics/children-of-incarcerated-parents.

- The Social Security Administration (SSA) finalized written statewide prerelease agreements in September with the Department of Corrections in Iowa and Kansas. These agreements '' now covering the majority of states '' ensure continuity of services for returning citizens. SSA also has prisoner SSN replacement card MOUs in place with 39 states and the Federal Bureau of Prisons. A dedicated reentry webpage is accessible at www.socialsecurity.gov/reentry.

- Increasing reentry service access to incarcerated veterans.

- In September, the Department of Labor's Veterans' Employment and Training Service announced the award of $1.5 million in grants to help once incarcerated veterans considered "at risk" of becoming homeless. In all, seven grants will serve more than 650 formerly incarcerated veterans in six states.

- The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) also has developed a web-based system '' the Veterans Reentry Search Service (VRSS) '' that allows prison, jail, and court staff to quickly and accurately identify veterans among their populations. The system also prompts VA field staff '' automatically '' so that they can efficiently connect veterans with services. As of this summer, more than half of all state prison systems, and a growing number of local jails, are now using VRSS to identify veterans in their populations.

- Improving opportunities for children of incarcerated parents and their families.

- In October, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) took action to make it easier for incarcerated individuals to stay in touch with their families by capping all in-state and interstate prison phone rates. The FCC also put an end to most of the fees imposed by inmate calling service providers. Studies have consistently shown that inmates who maintain contact with their families experience better outcomes and are less likely to return to prison after they are released. Reduced phone rates will make calls significantly more affordable for inmates and their families, including children of incarcerated parents, who often live in poverty and were at times charged $14 per minute phone rates.

- In October, the Department of Justice announced new grant awards to fund mentoring services for incarcerated fathers who are returning to their families. These awards will fund mentoring and comprehensive transitional services that emphasize development of parenting skills in incarcerated young fathers.

- Moreover, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention at the Department of Justice has awarded $1 million to promote and expand services to children who have a parent who is incarcerated in a Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) correctional facility. This program aims to provide opportunities for positive youth development, and to identify effective strategies and best practices that support children of incarcerated parents, including mentoring and comprehensive services that facilitate healthy and positive relationships. In addition to engaging the parent while he or she is incarcerated, this solicitation also supports the delivery of transitional reentry services upon release.

- Private Sector Commitments to Support Reentry.

- The Center for Employment Opportunities (CEO), an organization that provides comprehensive employment services to people with recent criminal convictions, has committed to more than double the number of people served from 4,500 to 11,000 across existing geographies and 3-5 new states. This winter, CEO will open in San Jose with support from Google and in the next year, the team will launch in Los Angeles. This growth has been catalyzed by federal investments, including support from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the Social Innovation Fund, and a Department of Labor Pay for Success Project.

- In addition, Cengage Learning will roll out Smart Horizons Career Online Education in correctional facilities in up to four new states over the next 12 months, providing over 1,000 new students with the opportunity to earn a high-school diploma and/or career certificate online. Smart Horizons Career Online Education is the world's first accredited online school district, with a focus on reaching underserved populations. The program has been piloted in Florida with 428 students who have received diplomas or certificates.

- Kwame Kilpatrick - Wikipedia

- American politician (born 1970)

- Kwame Malik Kilpatrick (born June 8, 1970) is an American former politician who served as the 72nd mayor of Detroit from 2002 to 2008. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously represented the 9th district in the Michigan House of Representatives from 1997 to 2002. Kilpatrick resigned as mayor in September 2008 after being convicted of perjury and obstruction of justice. He was sentenced to four months in jail and was released on probation after serving 99 days.

- In May 2010, Kilpatrick was sentenced to eighteen months to five years in state prison for violating his probation, [ 3 ] and served time at the Oaks Correctional Facility in northwest Michigan. In March 2013, he was convicted on 24 federal felony counts, including mail fraud, wire fraud, and racketeering. [ 4 ] In October 2013, Kilpatrick was sentenced to 28 years in federal prison, [ 5 ] and was incarcerated at the Federal Correctional Institution in El Reno, Oklahoma. In January 2021, after Kilpatrick had served 76 months of his 336-month sentence, President Donald Trump commuted his sentence. [ 6 ] [ 7 ]

- Early life, education, and family [ edit ] Kwame Malik Kilpatrick was born June 8, 1970, to Bernard Kilpatrick and Carolyn Cheeks Kilpatrick. His parents divorced in 1981. [ 8 ] Kilpatrick attended Detroit's Cass Technical High School and graduated from Florida A&M University with a Bachelor of Science degree in political science in 1992. While at FAMU, he played football under NFL Hall of Famer Ken Riley as an offensive tackle and was team captain. On September 9, 1995, he married Carlita Poles in Detroit. [ 9 ] They have three children together, Jalil, Jonas, and Jelani. [ 1 ] In 1999 he received a Juris Doctor from Detroit College of Law-Michigan State University [ 10 ] He has a sister Ayanna and a half-sister, Diarra. [ 8 ]

- Kilpatrick's mother Carolyn was a career politician, representing Detroit in Michigan House of Representatives from 1979 to 1996 and serving in the United States House of Representatives for Michigan's 13th congressional district from 1996 to 2010. She was not re-elected to office because she lost her primary election in August 2010 to State Senator Hansen Clarke. NPR and CBS News both noted that throughout her re-election campaign, Carolyn was dogged by questions about Kilpatrick following his tenure as mayor of Detroit. [ 11 ] [ 12 ]

- Kilpatrick's father Bernard was a semi-professional basketball player and politician. [ 8 ] He was elected to the Wayne County Commission, served as head of Wayne County Health and Human Services Department from 1989 to 2002, [ 13 ] and as chief of staff to former Wayne County Executive Edward H. McNamara. Later he operated a Detroit consulting firm called Maestro Associates. [ 14 ] [ 15 ]

- Kilpatrick filed for divorce from Carlita in 2018. [ 16 ] In July 2021 he married Laticia Maria McGee at Historic Little Rock Missionary Baptist Church in Detroit. [ 17 ]

- Michigan state representative [ edit ] Kilpatrick was elected to the Michigan House of Representatives in 1996 after his mother vacated her Detroit-based seat to mount a successful bid for Congress. [ 18 ] Kilpatrick's campaign staff consisted of high school classmates Derrick Miller and Christine Beatty, who became his legislative aide; later, Kilpatrick had an affair with Beatty. According to Kilpatrick, the campaign was run on a budget of $10,000 and did not receive endorsements from trade unions, congressional districts, or the Democratic establishment. [ 18 ]

- Kilpatrick was elected minority floor leader for the Michigan Democratic Party, serving in that position 1998 to 2000. He was subsequently elected as house minority leader in 2001, the first African-American to hold that position. [ 19 ] Later in 2001, Kilpatrick ran for mayor of Detroit, hiring Berg/Muirhead Associates for his campaign. They were retained as his public relations firm upon his election. [ 20 ] During the 2000 presidential election, Kilpatrick was a Michigan state co-chair of GoreNet. [ 21 ] GoreNet was a group that supported Al Gore's presidential campaign with a focus on grassroots and online organizing as well as hosting small dollar donor events. [ 22 ]

- In 2001, Kilpatrick used his influence while in the Michigan legislature to funnel state grant money to two organizations that were vague on their project description. The groups were run by friends of Kilpatrick and both agreed to subcontract work to U.N.I.T.E., a company owned by Kilpatrick's wife Carlita. Carlita was the firm's only employee, and the firm received $175,000 from the organizations. [ 23 ] [ 24 ] Detroit 3D was one of the groups and the State canceled its second and final installment of $250,000 because 3D refused to divulge details on how the funds were being spent. [ 23 ] [ 24 ]

- Mayor of Detroit (2002''2008) [ edit ] Kilpatrick greeting President George W. Bush in 2005On New Year's Day 2002, Kilpatrick became the youngest mayor of Detroit when he took office at age 31.

- During his first term, Kilpatrick was criticized for using city funds to lease a Lincoln Navigator for use by his family [ 25 ] and using his city-issued credit card to charge thousands of dollars' worth of spa massages, extravagant dining, and expensive wines. [ 26 ] [ 27 ] Kilpatrick paid back $9,000 of the $210,000 credit card charges. [ 19 ] Meanwhile, Kilpatrick closed the century-old Belle Isle Zoo and Belle Isle Aquarium because of the city's budget problems. The City Council overrode his funding veto for the zoo and gave it a budget of $700,000.

- In 2005, Time magazine named Kilpatrick as one of the worst mayors in America. [ 25 ] [ 28 ] [ 29 ]

- Special administratorship [ edit ] Since the 1970s, a federal judge had made the mayor of Detroit the special administrator of the Detroit Water Department because of severe pollution issues. When serious questions about water department contracts came to light in late 2005, Judge Feikens ended Kilpatrick's special administratorship in his capacity as mayor. In January 2006, The Detroit News reported that, "Kilpatrick used his special administrator authority to bypass the water board and City Council on three controversial contracts." These included a $131 million radio system for the city's police and fire departments, as well as a no-bid PR contract to a close personal aide. [ 30 ] But Judge Feikens praised Kilpatrick's work as steward of the department, referring questions on the contracts to the special master in charge of that investigation. [ 30 ]

- Rumored Manoogian Mansion party and Greene killing [ edit ] The Manoogian Mansion, official residence of the Mayor of DetroitIn the fall of 2002, it was alleged that Kilpatrick had held a wild party involving strippers at the Manoogian Mansion, the city-owned residence of the mayor of Detroit. Former members of the Executive Protection Unit (EPU), the mayor's police security detail, alleged that Carlita Kilpatrick, Kilpatrick's wife, came home unexpectedly and physically attacked an exotic dancer, Tamara Greene. [ 31 ] Officer Harold C. Nelthrope contacted the Internal Affairs unit of the Detroit Police Department in April 2003 to recommend that they investigate abuses by the EPU. Kilpatrick denied any wrongdoing. An investigation by Michigan Attorney General Cox and the Michigan State Police found no evidence that the party took place. [ 31 ]

- Greene was murdered on April 30, 2003, at around 3:40 a.m., near the intersection of Roselawn and West Outer Drive while sitting in her car with her 32-year-old boyfriend. [ 32 ] [ 33 ] She was shot multiple times with a .40 caliber Glock pistol. At the time, this was the same model and caliber firearm as those officially issued by the Detroit Police Department. The family believed the killing to have been a "deliberate hit". [ 33 ]

- Greene's family filed a $150 million lawsuit against the city of Detroit in federal court, claiming she was murdered to prevent her testimony about the Manoogian Mansion party. [ 33 ] In late 2011, Judge Gerald Ellis Rosen granted summary judgment in favor of the city. [ 34 ] Greene's children appealed the decision, but the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the district-court decision. [ 35 ] Several affidavits were filed in the lawsuit prior to its dismissal; in his summary-judgment order, Judge Rosen wrote, "[I]t is fair to say that the parties'--and, in particular, Plaintiffs'--were given wide latitude to pursue any and all matters that were arguably relevant to their claims or defenses". [ 36 ] Many affidavits related to whether the party took place and whether Carlita and Greene had been in an altercation. [ 37 ] [ 38 ] [ 39 ] Detroit Police lieutenant Alvin Bowman stated that he had suspected the shooter was a Detroit law-enforcement officer [ 32 ] and claimed that high-ranking Detroit Police personnel, including Cummings, deliberately sabotaged his investigation, stating that he was eventually transferred out of the Homicide Division because he had asked too many questions about the Greene murder and the Manoogian Mansion party. [ 32 ] Mayer Morganroth, the lawyer representing the city, said, "The Bowman affidavit is a little less than idiotic and more than absurd." [ 32 ]

- Denial of courtesy protection in Washington, D.C. [ edit ] In 2002, the Washington D.C. police announced that they would only offer professional courtesy protection to Kilpatrick while he was conducting official business in the nation's capital. D.C. police no longer provided after-hours police protection to Kilpatrick because of his inappropriate partying during past visits. Sergeant Tyrone Dodson of Washington D.C. explained by saying "we arrived at this decision because we felt that the late evening partying on the part of Mayor Kilpatrick would leave our officers stretched too thin and might result in an incident at one of the clubs." The Kilpatrick administration alleged that the statements and actions of the Washington D.C. police were part of a political conspiracy to "ruin" the mayor. [ 40 ]

- 2005 re-election campaign [ edit ] At a campaign rally in May 2005, Kilpatrick's father Bernard adamantly argued that allegations that the Mayor had held a party at the Manoogian Mansion were a lie, likening such statements to the false scapegoating of Jewish people by the Nazis. Bernard later apologized. [ 41 ] In October 2005, a third-party group supporting Kilpatrick, named The Citizens for Honest Government, generated controversy by its print advertisement that compared media criticism of the mayor to lynch mobs. [ 42 ]

- Kilpatrick and his opponent Freman Hendrix, both Democrats, each initially claimed victory. However, as the votes were tallied, it became clear that Kilpatrick had come back from his stretch of unpopularity to win a second term in office. Three months previously, most commentators declared his political career over after he was the first incumbent mayor of Detroit to come in second in a primary. Pre-election opinion polls predicted a large win for Hendrix; however, Kilpatrick won with 53% of the vote. [ 43 ] [ 44 ]

- Kilpatrick in 2006In July 2006, Kilpatrick was hospitalized and diagnosed with diverticulitis while in Houston, Texas. His personal physician indicated that Kilpatrick's condition may have been caused by a high-protein weight-loss diet. [ 45 ] That month, Detroit's City Council had voted unanimously to approve Kilpatrick's tax plan, with which he intended to offer homeowners some relief from the city's high property tax rates. The cuts ranged from 18% to 35%, depending on the property's value. [ 46 ]

- The city of Detroit was fourteen months late in filing its 2005''2006 audit. In March 2008, officials estimated the audit would cost an additional $2.4 million because of new auditing requirements that were not addressed by the city. The 2006''2007 fiscal year audit due on December 31, 2007, was expected to be eleven months late. [ 47 ]

- The state treasury chose to withhold $35 million of its monthly revenue sharing to the city and required Detroit to receive approval before selling bonds to raise money. [ 47 ] Kilpatrick told the City Council that he would take partial blame for the late audits because he laid off too many accountants, but he also blamed the firm hired to replace them. [ 48 ]

- Abuse of power allegations [ edit ] It was revealed on July 15, 2008, by WXYZ reporter Steve Wilson that, in 2005, Kilpatrick, Christine Beatty, and the chief of police Ella Bully-Cummings allegedly used their positions to help an influential Baptist minister arrested for soliciting a prostitute get his case dismissed. The arresting officer, Antoinette Bostic, was told by her supervisors that Mangedwa Nyathi was a minister (Assistant Pastor at Hartford Memorial Baptist Church on Detroit's west side), and that the mayor and police chief were calling to persuade Bostic not to show up to court, in which case the judge would be forced to dismiss the case against Nyathi. Bostic ignored her supervisors and appeared in court. [ 49 ]

- The defense lawyer, Charles Hammons, had the case postponed a couple of times and stated in court that "The mayor told me yesterday that this case is not gonna go forward." Hammons admitted to Wilson that this was the fact and that this was how many cases for people who know the mayor in Detroit are handled. Bully-Cummings angrily denied that she had ever asked her officers to perform such acts of impropriety. Kilpatrick stated that Wilson of WXYZ "was just making up stories again." [ 49 ]

- Reporting on nepotism and preferential hiring of friends and family [ edit ] A 2008 Detroit Free Press article revealed that at any given time there were about 100 appointees of Kilpatrick employed with the city. The Detroit Free Press examined city records and found that 29 of Kilpatrick's closest friends and family were appointed to positions within the various city departments. This hiring practice came to be known as 'the friends and family plan'. Some appointees had little to no experience, while others, among them Kilpatrick's uncle Ray Cheeks and cousin Nneka Cheeks, falsified their r(C)sum(C)s. Kilpatrick's cousin Patricia Peoples was appointed to the deputy director of human resources, giving her the ability to hire more of Kilpatrick's friends and family without such hirings being viewed as mayoral appointments. Although political appointments are not illegal, the sheer volume of Kilpatrick's appointments compared to all the appointments made by Detroit mayors since 1970, along with Kilpatrick's cutting of thousands of city jobs, made his appointments controversial. [ 50 ]

- The jobs held by friends and family ranged from secretarial positions to department heads. The appointees had an average salary increase of 36% compared with a 2% raise in 2003 and 2% raise in 2004 for fellow city workers. Some of the biggest salary increases were for April Edgar, half-sister of Christine Beatty, whose pay increase was 86% over 5 years. One of Kilpatrick's cousins, Ajene Evans, had a 77% increase in his salary during this 5-year period. The biggest salary increase among the 29 appointees was that of LaTonya Wallace-Hardiman who went from $32,500 staff secretary, to an executive assistant making $85,501'--163% in five years. [ 50 ]

- 2008 assault of a police officer [ edit ] On July 24, 2008, at approximately 4 p.m., Wayne County Sheriff's Detective Brian White and Joanne Kinney, an investigator from Wayne County Prosecutor Kym Worthy's office, went to the home of Kilpatrick's sister in an attempt to serve a subpoena. While on the front porch of the home, Kilpatrick came out of the house with his bodyguards and pushed the sheriff's deputy, as Sheriff Warren Evans said, "with significant force to make [the deputy] bounce into the prosecutor's investigator". The mayor yelled at Kinney "How can a black woman be riding in a car with a man named White?" [ 51 ]

- Evans went on to say "There were armed executive protection officers. My officers were there armed. And all of them had the consummate good sense not to let it escalate"... and "the two officers 'wisely' left the property and returned to their office to report on the incident." [ 52 ]

- Sheriff Evans stated that due to the "politically charged nature" of the incident, the case had been transferred to the Michigan State Police to investigate. Evans's daughter, who was on Kilpatrick's staff, [ 52 ] resigned shortly after this incident. [ 53 ]

- Events leading to resignation [ edit ] Text-messaging scandal and coverup [ edit ] In 2003, a civil lawsuit was filed against Kilpatrick by ex-bodyguard Harold Nelthrope and former Deputy Police Chief Gary Brown, who claimed they were fired in retaliation for an internal-affairs investigation. Brown had led the investigation, and Nelthrope had told investigators about the aforementioned rumors of a party that occurred at the Mayor's mansion. [ 54 ] Both claimed that Kilpatrick was motivated, in part, by his concern that the probe would uncover his extramarital affairs. [ 55 ] The trial began in August 2007. Kilpatrick and his chief of staff, Christine Beatty, both testified under oath that they were not involved in an extramarital affair. [ 56 ] [ 57 ] In September 2007, after three hours of deliberation, the jury found in favor of Nelthrope and Brown, awarding $6.5 million in damages. After the verdict was read, Kilpatrick said that the racial composition of the jury'--which was mostly white and suburban'--had played a role in the outcome and vowed an appeal. [ 55 ]

- Michigan Hall of Justice, home of the Michigan Supreme CourtIn October, plaintiffs' attorney Mike Stefani received thousands of text messages he had been endeavoring to obtain via subpoena'--the messages indicated an affair between Kilpatrick and Beatty. [ 58 ] [ 59 ] A day after he presented the files to the city's attorneys, Kilpatrick announced that he had agreed to settle the case, and the city counsel approved the $8.4 million deal, which included a proviso that Stefani would turn the files over to the mayor. [ 55 ] [ 60 ] [ 61 ] After the Detroit Free Press filed a Michigan Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, the proviso was removed from the main settlement document and put into a confidential supplement. [ 55 ] But the Detroit Free Press and The Detroit News filed a FOIA suit, seeking all settlement-related documents, [ 62 ] [ 63 ] and, in February 2008, the Michigan Supreme Court ordered the settlement documents be turned over to the plaintiffs. [ 64 ] The bulk of the text messages were released in late October 2008 by Circuit Court Judge Timothy Kenny, who instructed that some portions be redacted. [ 65 ]

- Michigan Governor Jennifer Granholm began an inquiry that led to the removal of Kilpatrick from office.Beatty resigned from her position as Kilpatrick's chief of staff. [ 66 ] The City Council requested that Kilpatrick resign as mayor and that Governor Granholm use her authority to remove him from office. [ 67 ] [ 68 ] Granholm said the inquiry was like a trial and that her role would be "functioning in a manner similar to that of a judicial officer." [ 67 ] Kilpatrick said he had paid back the $8.4 million through "hard work for the city" and dismissed any intentions of removing himself from office as "political rhetoric". [ 69 ]

- 2008 State of the City address [ edit ] In March 2008, Kilpatrick delivered his seventh "State of the City" address to the city of Detroit. The speech marked a turning point in his career. The majority of the 70-minute speech focused on positive changes occurring throughout Detroit and future plans. Kilpatrick specifically noted increased police surveillance, new policing technologies, and initiatives to rebuild blighted neighborhoods. He received repeated standing ovations from the invitation-only audience.

- Toward the end of the speech, Kilpatrick deviated from the transcript given to the media [ 70 ] and posted on his official website [ 71 ] to address the scandals and controversies surrounding his years in office, saying that the media had focused on those controversies only to increase their viewership, and that their focus had led to racist attacks against him and his family.

- Kilpatrick's comments generated many negative responses. Michigan Governor and fellow Democrat Jennifer Granholm issued a statement in which she condemned the use of the N-word in any context. [ 72 ] Michigan Attorney General Mike Cox stated on WJR talk radio that he thought that using the N-word was "reprehensible", saying, "I thought his statements were race-baiting on par with David Duke and George Wallace, all to save his political career. I'm not a Detroiter, but last night crossed the line ... those statements not only hurt Detroit, [but] as long as the mayor is there, he will be a drag on the whole region." Cox said that whether Kilpatrick is criminally charged or not, he should resign as mayor. Former Kilpatrick political adviser Sam Riddle labeled the address a race-baiting speech. "It's an act of desperation to use the N-word," said Riddle. "He's attempting to regain his base of support by playing the race card. He's gone to that well one too many times." [dead link ]

- The Wayne County Election Committee approved a recall petition to remove Kilpatrick as mayor based, in part, on the accusation that Kilpatrick misled the City Council into approving the settlement. The recall petition was filed by Douglas Johnson, a city council candidate. [ 74 ] Kilpatrick appealed to the commission to reconsider its decision on the grounds that Johnson was not a resident of Detroit. [ 75 ] Johnson also requested that Jennifer Granholm use her power as Governor to remove Kilpatrick from office.

- On March 12, 2008, at the request of the Mayor's office, Wayne County Election Commission rescinded its earlier approval for the recall. The Mayor's office argued that there was not any evidence that the organizer, Douglas Johnson, actually resided within the city limits of Detroit. Johnson stated that his group would refile using another person whose residency would not be an issue. [ 76 ] On March 27, 2008, a second recall petition was filed against Kilpatrick by Angelo Brown. Brown stated in his filing that Kilpatrick is too preoccupied with his legal problems to be effective. Kilpatrick's spokesman James Canning again dismissed this latest recall by saying: "It's Mr. Brown's right to file a petition, but it's just another effort by a political hopeful to grab headlines." [ 77 ]

- On May 14 the Detroit City Council voted to request that the governor of Michigan, Jennifer Granholm, remove Kilpatrick from office. [ 78 ]

- Criminal charges and resignation [ edit ] On March 24, 2008, Wayne County Prosecutor Kym Worthy announced a twelve-count criminal indictment against Kilpatrick and Beatty, charging Kilpatrick with eight felonies and Beatty with seven. Charges for both included perjury, misconduct in office, and obstruction of justice. Worthy suggested that others in the Kilpatrick administration could also be charged. [ 79 ] The preliminary examination scheduled for September 22, 2008, was waived by both defendants, thereby allowing the case to proceed directly to trial. [ 80 ] [ 81 ]

- In July 2008, Kilpatrick violated the terms of his bail by briefly traveling to Windsor, Ontario, where he met with Windsor mayor Eddie Francis concerning a deal to have the city of Windsor take over operational control of the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel in exchange for a $75 million loan. [ 82 ] As a result, on August 7, 2008, Kilpatrick was remanded to spend a night in the Wayne County Jail. It was the first time in history that a sitting Detroit mayor had been ordered to jail. In issuing the order, Chief Judge Ronald Giles stated that he could not treat the mayor differently from "John Six-Pack." [ 83 ] [ 84 ] On August 8, 2008, after arguments on Kilpatrick's behalf by attorneys Jim Parkman and Jim Thomas, Judge Thomas Jackson reversed the remand order and permitted Kilpatrick to be released on posting a $50,000 cash bond and the further condition that the mayor not travel, and wear an electronic tracking device.

- The same day Kilpatrick was released under the second bail agreement, Michigan Attorney General Mike Cox announced that two new felony counts had been filed against the mayor for assaulting or interfering with a law officer. The new charges arose out of allegations that Kilpatrick on July 24, 2008, shoved two Wayne County Sheriff's Deputies who were attempting to serve a subpoena on Bobby Ferguson, a Kilpatrick ally, and a potential witness in the mayor's then-upcoming perjury trial.[citation needed ]

- On September 4, 2008, Kilpatrick announced his resignation as mayor, [ 85 ] effective September 18, [ 86 ] and pleaded guilty to two felony counts of obstruction of justice and pleaded no contest to assaulting the deputy. [ 86 ] [ 87 ] Kilpatrick had agreed to resign as part of the plea agreement, in which he also agreed to serve four months in the Wayne County Jail, pay one million dollars of restitution to the city of Detroit, surrender his license to practice law, submit to five years probation and not run for public office during his probation period, and surrender his state pension from his six years' service in the Michigan House of Representatives before being elected mayor. In an allocution given as part of his plea, Kilpatrick admitted that he lied under oath several times.[citation needed ]

- In the separate assault case, he pleaded no contest to one felony count of assaulting and obstructing a police officer in exchange for a second assault charge being dropped. This deal also required his resignation and 120 days in jail, to be served concurrently with his jail time for the perjury counts. [ 88 ] Kilpatrick was sentenced on October 28, 2008. The judge ordered that Kilpatrick not be given an opportunity for early release, but instead serve the entire 120 days in jail. [ 89 ]

- Detroit City Council President Kenneth Cockrel, Jr. replaced Kilpatrick as mayor at 12:01 a.m. September 19, 2008.

- Judge David Groner sentenced Kilpatrick to four months in jail on October 28, 2008, calling him "arrogant and defiant" and questioning the sincerity of a guilty plea that ended his career at City Hall. The punishment was part of a plea agreement worked out a month earlier. "When someone gets 120 days in jail, they should get 120 days in jail," Groner said. Kilpatrick also was given a 120-day concurrent sentence for assaulting a sheriff's officer who was trying to deliver a subpoena in July. [ 90 ] He was seen smirking, laughing, and even calling the sentencing a "joke". [ 91 ]

- Wayne County Sheriff Warren Evans said that they take 40,000 prisoners into the prison annually, but that Kilpatrick would be kept separate from the general population and "won't be treated any worse or any better than other prisoners."He was housed in a secured, 15 feet by 10 feet cell with a bed, chair, toilet and a shower, spending approximately 23 hours a day there. [ 92 ] At 12:35 a.m. on Tuesday, February 3, 2009, Kilpatrick left jail after serving 99 days. He boarded a privately chartered Lear jet and landed in Texas that evening. [ 93 ] He was supposed to join his family in a $3,000 per month rental house in Southlake, Texas. [ 94 ]

- Within a couple of weeks, Kilpatrick was hired by Covisint, a Texas subsidiary of Compuware, headquartered in Detroit. CEO of Compuware Peter Karmanos, Jr. was one of the parties who loaned large sums of money to Kilpatrick in late 2008. [ 95 ] Kilpatrick was let go from Compuware in May 2010 after being sentenced to prison. [ 96 ]

- Restitution hearing [ edit ] Kilpatrick claimed poverty to Judge David Groner. He said he only had $3,000 per month (later lowered to $6) for the restitution payments. [ 97 ]

- Judge Groner requested detailed financial records for Kilpatrick, his wife, their children, etc. By November 2009, Kilpatrick was on the stand in Detroit to explain his apparent poverty. He claimed to have no knowledge about who paid for his million-dollar home, Cadillac Escalades, and other lavish expenses. The former mayor also denied any knowledge of his wife's finances, or even whether she was employed. During this hearing, it was revealed that Peter Karmanos Jr., Roger Penske and other business leaders had provided substantial monies to the Kilpatricks to convince the mayor to resign his office and plead guilty. [ 98 ] On January 20, 2010, Judge Groner ruled that Kilpatrick pay the sum of $300,000 to the city of Detroit within 90 days. [ 99 ]

- July 2010 mugshot of KilpatrickOn February 19, 2010, Kilpatrick missed a required restitution payment of $79,000. The court received only $14,000 on February 19 and then only another $21,175 on February 22. On February 23, Judge Groner approved a warrant for Kilpatrick and ruled in April that he had violated the terms of his probation. On May 25, 2010, Kilpatrick was sentenced to one and a half to five years with the Michigan Department of Corrections (with credit for 120 days previously served) for violation of probation, [ 100 ] and was afterwards taken back into correctional custody. He was housed for fourteen days in the hospital unit of the state prisoner reception center. [ 101 ] Kilpatrick was later housed in the Oaks Correctional Facility. [ 102 ]

- After he was indicted in federal court for additional crimes related to alleged misuse of his campaign funds, Kilpatrick lobbied for a transfer from the Oaks Correctional Facility. [ 103 ] On July 11, 2010, he was transferred into the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP). [ 101 ] Kilpatrick was incarcerated in the Milan Federal Prison near Milan, Michigan. [ 104 ] He was released from federal custody on April 6, 2011. [ 105 ] During his final 118 days of state imprisonment, Kilpatrick resided in the Cotton Correctional Facility. [ 101 ] Kilpatrick was released on parole on August 2, 2011. [ 106 ] [ 107 ] [ 108 ] In August 2011 the court ordered Kilpatrick to pay for his incarceration costs. [ 101 ]

- Second criminal trial and conviction [ edit ] On December 14, 2010, Kilpatrick was again indicted on new corruption charges, in what a federal prosecutor called a "pattern of extortion, bribery and fraud" by some of the city's most prominent officials. His father, Bernard Kilpatrick, was also indicted, as was contractor Bobby Ferguson; Kilpatrick's aide, Derrick Miller; and Detroit water department chief Victor Mercado. [ 4 ] [ 109 ] The original 38-charge indictment listed allegations of 13 fraudulent schemes in awarding contracts in the city's Department of Water and Sewerage, with pocketed kickbacks of nearly $1,000,000. He was arraigned on January 10, 2011, on charges in the 89-page indictment. Federal prosecuting attorneys proposed a trial date in January 2012, but defense attorneys asked for a trial date in the summer of 2012. [ 110 ]

- Opening statements in the trial began on September 21, 2012. [ 111 ] [ 112 ] Prosecutors soon brought forth a large number of witnesses who gave damaging testimony. [ 113 ] Mercado took a plea deal while the trial was in progress. [ 114 ] On March 11, 2013, in spite of a vigorous defense that cost taxpayers more than a million dollars, [ 115 ] Kilpatrick was found guilty by a jury on two dozen counts including those for racketeering, extortion, mail fraud, and tax evasion, among others. Shortly after conviction, speaking about Kilpatrick, Judge Nancy Edmunds ruled in favor of remand saying "detention is required in his circumstance". [ 116 ]

- He was sentenced to 28 years in prison on October 10, 2013. [ 5 ] [ 117 ] Kilpatrick, Federal Bureau of Prisons Register #44678-039, was serving his sentence at Federal Correctional Institution, Oakdale, a low-security prison in Oakdale, Louisiana. There is no parole in the federal prison system. However, with time off for good behavior, his earliest possible release date was August 1, 2037'--when he would be 67 years old. [ 118 ] [ 119 ]

- Mercado pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy, Bobby Ferguson was sentenced to 21 years in prison, [ 120 ] Derrick Miller pleaded guilty to tax evasion and was sentenced to three years supervision, the first year in a halfway house. [ 121 ] [ 122 ] Bernard Kilpatrick was sentenced to 15 months in prison. [ 123 ] Emma Bell received two years probation and was fined $330,000 in back taxes as part of a plea deal where she testified that she frequently handed Kilpatrick large amounts of cash skimmed from campaign accounts. [ 124 ]

- First Independence Bank, used by Kilpatrick and Ferguson, was fined $250,000 for failing to follow anti-money-laundering regulations. [ 125 ] 14 companies were suspended from bidding on contracts with the water department in the wake of the scandal. Inland Waters Pollution Control Inc. paid $4.5 million in the settlement of a lawsuit over their involvement with Kilpatrick, Ferguson and the Detroit Water Board. [ 126 ] Lakeshore TolTest Corp. reached a $5 million settlement with the Water Board to avoid litigation. [ 127 ]

- In August 2015, the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit upheld his convictions but ordered that the amount of restitution be recalculated. [ 128 ] In June 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court denied his appeal. [ 129 ]

- In June 2018 Kilpatrick began seeking a pardon from President Donald Trump. [ 130 ] His application was opposed by the U.S. Attorney's Office for southeast Michigan. [ 131 ] Restitution claims and other civil lawsuits accumulated claimed $10 million in debts, for which Kilpatrick is responsible. Kilpatrick has no assets to settle these claims. [ 132 ]

- Commutation of sentence [ edit ] On January 20, 2021, President Donald Trump commuted Kilpatrick's sentence with less than 12 hours remaining before he was due to leave office as president. [ 133 ] The White House statement on the pardoning of Kilpatrick reads: "Mr. Kilpatrick has served approximately 7 years in prison for his role in a racketeering and bribery scheme while he held public office. During his incarceration, Mr. Kilpatrick has taught public speaking classes and has led Bible Study groups with his fellow inmates." [ 133 ]

- President Trump's commutation allowed Kilpatrick to gain release 20 years early, though it did not vacate his conviction. [ 7 ] The commutation left in place the almost $4.8 million in restitution and the three-year probation. [ 134 ] Kilpatrick will not be able to run for office in Michigan until 2033 as a felon is excluded from politics for 20 years after conviction under Michigan law. [ 135 ]

- Other post-mayoral legal developments [ edit ] In 2012, the Securities and Exchange Commission charged Kilpatrick and former city treasurer Jeffrey W. Beasley for having received $180,000 in travel, hotel rooms, and gifts from a company seeking investments from the city pension fund. Chauncey C. Mayfield and his company were also brought before administrative proceedings. [ 136 ] The company received a $117 million investment in a real estate investment trust that it controlled. [ 137 ] [ 138 ] MayfieldGentry proceeded to misappropriate $3.1 million from the pension fund which was revealed during the influence peddling investigation. [ 139 ] Mayfield pleaded guilty in 2013. The case was scheduled for June 2014. [ 140 ]

- According to The Detroit News (June 24, 2010), Kilpatrick, his father Bernard, and the Kilpatrick Civic Fund may have been important figures in the sludge hauling contract that saw city council president Monica Conyers (wife of Rep. John Conyers) and her chief of staff Sam Riddle convicted for conspiracy and bribery. "Kilpatrick and his father also figured, but have not been charged, in evidence surrounding a bribery-tainted, $1.2 billion sewage sludge contract the Detroit City Council awarded to Synagro Technologies Inc. in 2007. According to court documents and people familiar with the case, former Synagro official James Rosendall made large contributions to the Kilpatrick Civic Fund and gave Kilpatrick free flights to Las Vegas and Mackinac Island. Rosendall also told investigators he made cash payments to Bernard N. Kilpatrick, who told Rosendall he got him access to City Hall, records show." [ 141 ] Rosendall and a Synagro consultant Rayford Jackson were also convicted of bribery.

- Kilpatrick co-wrote a memoir about his life and political experiences titled Surrendered: The Rise, Fall, & Revelation of Kwame Kilpatrick. [ 142 ] The book was originally scheduled for release on August 2, 2011, a date that would have just barely preceded his scheduled release from a Michigan prison. [ 143 ] However, the publisher delayed the release to August 9, almost a week after Kilpatrick was paroled. Kilpatrick appeared at public events in Michigan and elsewhere to promote his book. [ 144 ]

- The public prosecutor in Wayne County, Michigan has asked the state courts to order the book's publisher, Tennessee-based Creative Publishing Consultants Inc., to remit Kilpatrick's share on the book's proceeds for payment toward Kilpatrick's criminal restitution and his cost of incarceration. [ 145 ] On November 16, 2011, the publisher's attorney failed to appear at a hearing on the matter in Wayne County Circuit Court. A bench warrant was issued for the attorney, Jack Gritton, and was forwarded to authorities in Tennessee, where Gritton's practice is based. [ 146 ]

- Post-release activities [ edit ] Since release, Kilpatrick has worked as an "ordained minister, motivational speaker, consultant, and certified character coach". [ 147 ] In April 2023, Kilpatrick was a guest speaker at the "Black Agenda Movement" conference, organized by YouTuber Michelle R. Kulczyk (Meechi X). [ 148 ]

- On June 15, 2024, Kilpatrick endorsed Donald Trump in the 2024 United States presidential election. [ 149 ]

- 2005 Race for Mayor (Detroit)Kwame Kilpatrick (D) (incumbent), 53%Freman Hendrix (D), 47%2005 Race for Mayor (Detroit) (Primary Election)Freman Hendrix (D), 45%Kwame Kilpatrick (D) (incumbent), 34%Sharon McPhail (D), 12%Hansen Clarke (D), 8%2001 Race for Mayor (Detroit)Kwame Kilpatrick (D), 54%Gil Hill (D), 46%As a politician, Kilpatrick was a member of the Democratic Party. [ 150 ]

- Kilpatrick was a member of the Mayors Against Illegal Guns Coalition, a bi-partisan anti-gun group with a stated goal of "making the public safer by getting illegal guns off the streets." The Coalition was co-chaired by Mayor Thomas Menino of Boston and Michael Bloomberg of New York City. Following Kilpatrick's conviction in 2013 on federal charges, his membership status in the organization was initially not clear. As of September 2010, there had been no announcement of his resignation from Mayors Against Illegal Guns; however, by December 2012, he was no longer listed as a member. [ 151 ]